Remember when our biggest worries came from the silver screen rather than the evening news? The 1980s gave us economic anxieties and Cold War tensions, sure, but nothing quite matched the primal fear of watching a truly memorable villain do their thing in the darkness of the movie theater. From slasher icons to corporate sharks, these cinematic baddies kept us up at night in ways that real-world problems somehow couldn’t—they were immediate, visceral, and haunted our dreams long after the credits rolled.

1. Darth Vader (The Empire Strikes Back, 1980)

Though introduced in the ’70s, Vader reached his terrifying peak in “Empire” when he revealed his true connection to Luke Skywalker. His imposing black armor, mechanical breathing, and willingness to force-choke his own officers made him the embodiment of totalitarian power gone mad. That scene in Cloud City, with the dining room ambush and subsequent revelation, traumatized an entire generation more effectively than any nuclear war documentary ever could. Screen Rant has assembled a list of the many actors who left their mark on the role of Darth Vader.

James Earl Jones’s deep, resonant voice gave Vader a gravitas that still sends shivers down our spines decades later. The character’s redemption arc was still years away, and in 1980, he represented the ultimate unstoppable force of evil in the galaxy. Nothing on the nightly news about Soviet missiles could compete with watching Vader casually dismember his own son and then invite him to join the family business.

2. The Thing (The Thing, 1982)

John Carpenter’s alien monstrosity could be anyone—literally—as it perfectly mimicked human beings before revealing its grotesque true form. The paranoia this creature generated, making characters question who among them was still human, tapped into fears deeper than anything CNN reported. Those practical effects transformations—with stretching flesh, splitting heads, and spider-like appendages—were more viscerally disturbing than any real-world disaster footage. Authors on the Roger Ebert site writes fondly on the efficient use of the cold and confusing atmosphere that the film maintains as a pedestal for its iconic, terrifying villain.

The Thing’s assimilation abilities created a monster that was fundamentally unknowable, a predator that attacked our very sense of identity. Each death scene pushed the boundaries of what special effects could achieve, creating nightmare fuel that made real-world concerns temporarily fade away. Kurt Russell’s flamethrower might have provided some catharsis, but the film’s ambiguous ending left us forever wondering if the creature might still be out there, waiting.

3. Hans Gruber (Die Hard, 1988)

Alan Rickman’s sophisticated terrorist-thief made villainy look effortlessly elegant, with his tailored suit and cultured accent masking a ruthless willingness to execute hostages. His cold intelligence and adaptability made him far more terrifying than the faceless criminals described in evening news segments. The way he could switch from quoting classical literature to ordering an execution without changing his tone created a villain who seemed capable of anything. According to The Guardian, Rickman came very close to turning down this memorable role.

Gruber’s meticulous planning and quick thinking made him the perfect foil for Bruce Willis’s everyman hero. His calculated cruelty—like threatening to shoot hostages to get what he wanted—felt personally threatening in a way that abstract economic downturns never could. When he finally plummeted from the Nakatomi Plaza, audiences actually felt relief more intense than when real-world crises were resolved.

4. Freddy Krueger (A Nightmare on Elm Street, 1984)

Robert Englund’s burned dream-stalker made the simple act of falling asleep a potentially deadly proposition for teenagers everywhere. His striped sweater, fedora, and knife-fingered glove became instantly iconic symbols of supernatural terror that overshadowed real-world bogeymen. The idea that Krueger could kill you in your dreams—where no parent, police officer, or locked door could protect you—exploited a primal vulnerability we all share.

Krueger’s twisted sense of humor made him uniquely disturbing, often taunting his victims with darkly comic one-liners before dispatching them. His ability to manipulate dream reality meant his kills were limited only by imagination, resulting in death scenes far more memorable than anything on the evening news. Parents across America found themselves comforting children who’d rather stay awake indefinitely than face the possibility of meeting Freddy in their nightmares.

5. The Terminator (The Terminator, 1984)

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s relentless cyborg assassin pursued Sarah Connor with a mechanical determination that made human criminals seem positively reasonable by comparison. The T-800’s emotionless pursuit, superhuman strength, and ability to withstand seemingly fatal damage created an unstoppable force that dominated our nightmares. When Arnold delivered the line “I’ll be back,” we believed him with a certainty that made distant geopolitical threats seem almost quaint.

James Cameron gave us a glimpse of a technological apocalypse far more visceral than any real-world prediction. The final scene showing the exoskeleton continuing to crawl forward despite losing its lower body embodied a terror of technological progress gone wrong. Real scientists might have worried about computers taking jobs, but we worried about them taking lives after watching the Terminator methodically eliminate everyone in its path.

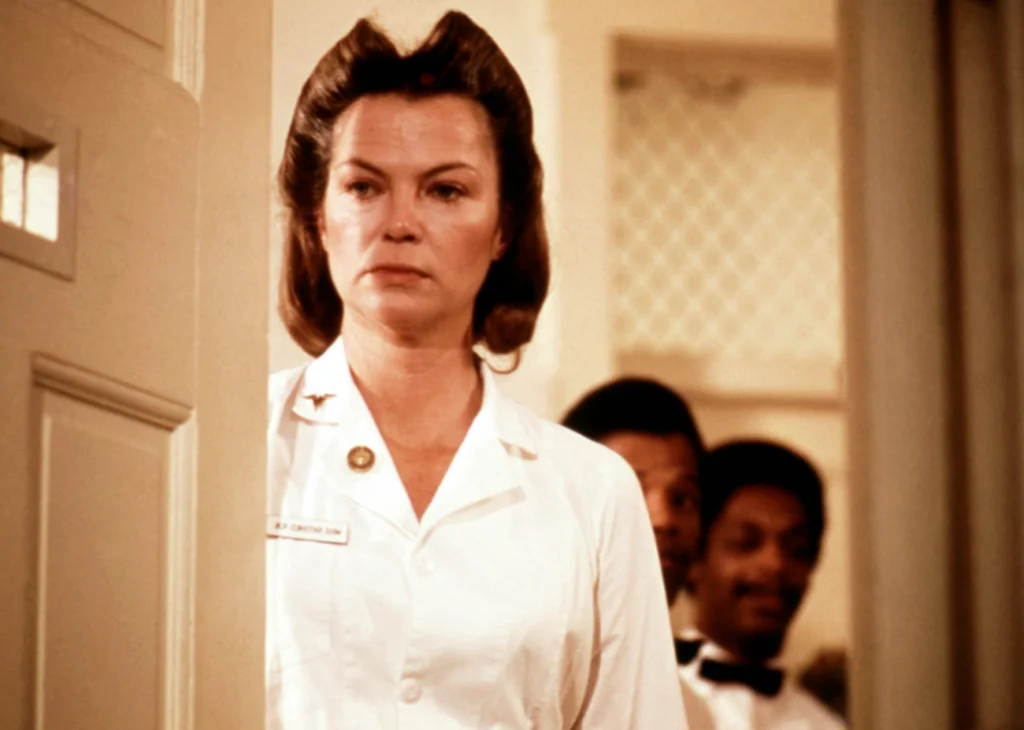

6. Nurse Ratched (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975/Cable TV staple of the ’80s)

Though the film was released in 1975, Louise Fletcher’s coldly authoritarian nurse became a cable TV fixture throughout the ’80s, exposing new audiences to her particular brand of institutional cruelty. Her calm demeanor and position of absolute authority made her abuses of power all the more chilling to viewers. The way she could destroy a man’s spirit while maintaining a professional smile tapped into our fears of powerlessness within faceless systems.

Ratched’s villain status came not from violence but from her methodical emotional and psychological manipulation of vulnerable patients. Her final victory over McMurphy—reducing the once-vibrant rebel to a lobotomized shell—felt more devastating than any slasher film murder. Many of us grew up more afraid of ending up under the care of someone like Nurse Ratched than of any headline-making disaster or crime spree.

7. Clarence Boddicker (RoboCop, 1987)

Kurtwood Smith’s sadistic crime boss embodied the urban decay anxieties of the ’80s, but with a gleeful malevolence that real criminals rarely displayed. His casual brutality—like the infamous “Can you fly, Bobby?” scene—showed a man who enjoyed inflicting suffering far more than any real criminal profiled on “60 Minutes.” The way he spat his lines through oversized glasses created a disturbing contrast between his nerdy appearance and his psychopathic behavior.

Boddicker’s corruption extended beyond street crime to corporate conspiracy, making him a perfect villain for the excess-driven ’80s. His gang’s execution of Officer Murphy was so brutal and prolonged that it seared itself into viewers’ memories more effectively than any real-world violence. When he finally got his comeuppance, audiences cheered with a satisfaction rarely felt when reading about actual criminals being brought to justice.

8. Roy Batty (Blade Runner, 1982)

Rutger Hauer’s philosophical replicant created existential dread through his superhuman abilities combined with very human emotions. His poetic violence and quest for more life made him a complex antagonist whose motives were disturbingly understandable. The scene where he crushes his creator’s skull while demanding answers about his limited lifespan explored fears of mortality more viscerally than any medical news report.

Batty’s famous “tears in rain” monologue complicated our fear by making us empathize with the very entity we’d been afraid of throughout the film. His glowing eyes and bleached hair created an uncanny appearance that straddled the line between human and other. When he saved Deckard despite having every reason to let him die, Batty forced us to confront uncomfortable questions about what constitutes humanity—questions far more personally unsettling than distant international conflicts.

9. Jack Torrance (The Shining, 1980)

Jack Nicholson’s descent into homicidal madness at the Overlook Hotel made domestic violence far more terrifying than any crime statistics. His transformation from struggling writer to axe-wielding maniac exploited our fears of loved ones becoming unrecognizable. That “Here’s Johnny!” moment, with the splintering door and maniacal grin, made viewers jump more than any actual news footage.

Torrance represented the horror of watching someone familiar become something monstrous and unpredictable. His pursuit of his own family through the hotel’s maze created a primal terror that distant world events simply couldn’t match. The thought that isolation and supernatural influence could turn a father against his family tapped into anxieties far more immediate than any Cold War posturing.

10. Khan Noonien Singh (Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, 1982)

Ricardo Montalban’s revenge-obsessed superhuman brought Shakespearean levels of charismatic menace to science fiction. His genetically enhanced intelligence and strength, combined with an unquenchable thirst for vengeance, created a villain whose emotional intensity overshadowed real-world antagonists. Khan’s famous line about pursuing Kirk, even at the cost of his own life, demonstrated a level of commitment to destruction that made real-world conflicts seem rational by comparison.

The character’s memorable chest-baring costume and theatrical delivery might seem campy today, but they created an unforgettable presence that burned itself into our collective memory. His willingness to detonate the Genesis device as a final act of spite showed a level of malevolence that few real-world figures could match. When Spock sacrificed himself to save the Enterprise crew from Khan’s final attack, the emotional impact hit harder than any real-world tragedy of the decade.

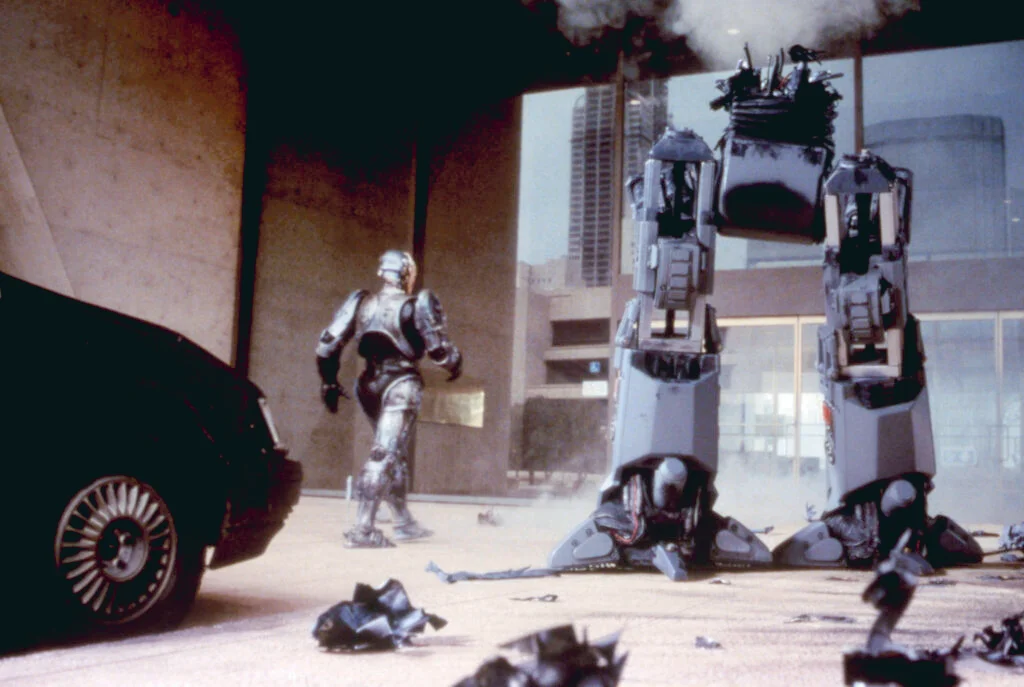

11. ED-209 (RoboCop, 1987)

This malfunctioning law enforcement droid represented corporate callousness and technological failure in one terrifying package. Its iconic boardroom malfunction, where it gunned down an executive during a demonstration, played on our worst fears about putting machines in charge of life-or-death decisions. The stop-motion animation gave ED-209 a jerky, unpredictable quality that made its movements seem alien and threatening.

The droid’s distinctive roar and massive armaments made it an imposing physical threat throughout the film. Its inability to navigate stairs—despite its otherwise overwhelming firepower—provided a rare moment of weakness that humanized our fear of unstoppable technology. ED-209 embodied anxieties about automation and corporate oversight that felt more immediate than abstract concerns about the economy or political shifts.

12. The Xenomorph (Aliens, 1986)

While first introduced in 1979’s “Alien,” James Cameron’s sequel multiplied our terror by showing these perfect killing machines hunting in packs. Their acid blood, extendable inner jaws, and ability to move through walls and ceilings made them predators with no natural weakness. The scene where they stealthily descended from the ceiling panels around the colonists created a sense of hopeless encirclement more visceral than any news about being surrounded by national adversaries.

H.R. Giger’s biomechanical design gave the creatures a disturbing sexual undertone that operated on a subconscious level. The lifecycle involving face-huggers and chest-bursters exploited our deep-seated fears about bodily violation and unwanted pregnancy. Watching these creatures systematically eliminate highly trained Colonial Marines made us question whether humanity would actually win in an encounter with a truly alien intelligence—a philosophical horror deeper than any contemporary real-world threat.

The beauty of these villains lies in how they’ve remained in our cultural consciousness long after the real fears of the ’80s faded into history books. While Wall Street crashes, political scandals, and international tensions dominated headlines, these fictional antagonists worked their way into our psyches on a deeper level. Perhaps that’s the true power of great movie villains—they give tangible form to abstract anxieties, allowing us to process our fears through the safety of fiction. And unlike real-world problems that eventually resolve or transform, these characters remain perfectly preserved in cinematic amber, ready to terrify new generations discovering them for the first time.