Remember when movies didn’t spoon-feed us everything? Back in our day, filmmakers weren’t afraid to leave audiences thinking long after the credits rolled. Those were the times when we’d pile into wood-paneled station wagons or crowd into smoke-filled theaters, only to emerge hours later debating what in the world we’d just witnessed. Some of these cinematic mind-benders from the ’60s and ’70s continue to perplex us decades later, sparking conversations at family reunions and nostalgic get-togethers to this day.

1. “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s space epic concludes with astronaut Dave Bowman aging rapidly in a strange white room before transforming into the enigmatic “Star Child” floating above Earth. The psychedelic journey through the monolith’s stargate and the surreal bedroom sequence left audiences in 1968 utterly baffled, with many walking out of theaters wondering if they’d missed something important. Decades later, film scholars still debate the precise meaning of the finale, with interpretations ranging from human evolution to transcendence beyond physical form. The Hundreds writes that the scope of this movie’s cultural impact couldn’t have been anticipated.

Those final moments represent the pinnacle of Kubrick’s artistic vision, deliberately crafted to provoke thought rather than provide neat answers. The mysterious ending was so controversial that theater owners reported receiving angry calls from confused patrons demanding explanations. Yet this ambiguity is precisely what has allowed “2001” to remain relevant, with each generation discovering new layers of meaning in those strange final scenes that continue to defy simple explanation.

2. “Planet of the Apes” (1968)

Charlton Heston’s discovery of the Statue of Liberty half-buried in sand delivered one of cinema’s most shocking twist endings, revealing he had been on Earth all along. The gut-punch realization that humans had destroyed their own civilization and allowed apes to become the dominant species transformed what might have been just another sci-fi adventure into a profound commentary on the Cold War era. The image of Heston pounding the sand in despair became instantly iconic, a powerful warning about humanity’s self-destructive tendencies. Comic Book Resources praises this movie for establishing a legacy that endures to this day.

Director Franklin J. Schaffner crafted this finale to serve as both a narrative surprise and a sobering wake-up call about nuclear proliferation. The film’s writer Rod Serling, fresh from his success with “The Twilight Zone,” knew exactly how to deliver a conclusion that would haunt viewers long after leaving the theater. Even those who’ve never seen the film recognize the ending’s cultural significance, cementing “Planet of the Apes” as more than entertainment but a powerful piece of social commentary that still resonates with viewers concerned about humanity’s future.

3. “Solaris” (1972)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Soviet science fiction masterpiece concludes with the revelation that the protagonist Kris has chosen to remain on an island that’s actually a simulation created by the sentient planet Solaris. The film’s final shot pulls back to reveal the island as a small formation on the surface of the alien planet, suggesting Kris has abandoned authentic human existence for a comforting illusion. This metaphysical twist challenged viewers to consider profound questions about the nature of reality, memory, and what constitutes genuine human connection. Game Rant also offers some more thoughts on the matter of the remake’s equally open-ended conclusion.

The deliberately paced finale confused many viewers expecting conventional science fiction resolutions focused on alien contact or technological solutions. Instead, Tarkovsky offers a deeply philosophical meditation on grief and the human tendency to retreat into comforting falsehoods rather than confront painful truths. Western audiences, who often saw only heavily edited versions of the film until recent restorations, found the ending particularly perplexing without the context of key scenes that illuminated Kris’s psychological journey.

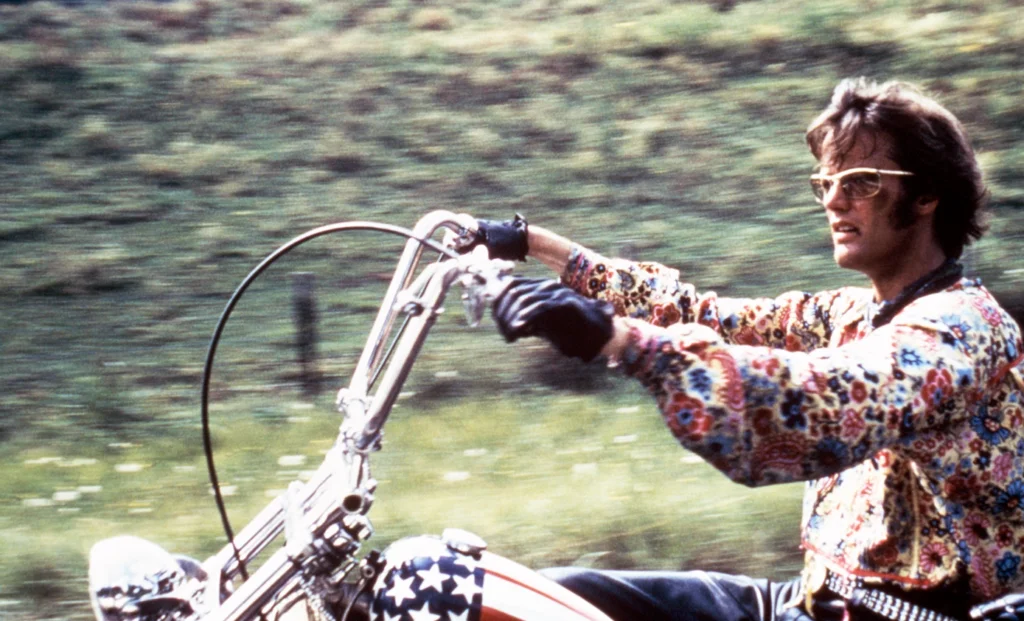

4. “Easy Rider” (1969)

Dennis Hopper’s counterculture classic ends abruptly with the senseless killing of the protagonists by shotgun-wielding locals, cutting off their journey with shocking finality. The unexpected violence of the conclusion served as a powerful metaphor for the death of 1960s idealism and the harsh reality awaiting those who challenged conservative America. Audiences who had been enjoying the free-spirited road trip were left stunned by the nihilistic ending, which offered no redemption or meaning to the characters’ deaths.

The bleak finale represented a stark departure from Hollywood conventions, where even tragic endings typically provided some form of moral resolution or catharsis. Producer/star Peter Fonda later revealed that the controversial conclusion was partly inspired by the assassination of prominent political figures during that turbulent decade. The film’s final line—”We blew it”—became a mournful epitaph not just for the characters but for an entire generation’s failed dreams of transforming America.

5. “The Graduate” (1967)

Mike Nichols concludes his generation-defining film with Benjamin and Elaine sitting on the back of a bus, their expressions gradually shifting from exhilaration to uncertainty after their dramatic church escape. What makes this ending so enduring is how it undermines the conventional romantic comedy structure, suggesting that impulsive passion might not translate to lasting happiness. The camera lingers uncomfortably on their faces as reality sets in, with Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” emphasizing the hollow victory they’ve achieved.

The ambiguous finale perfectly captured the mood of a generation suspicious of their parents’ values yet unsure of what should replace them. Dustin Hoffman and Katharine Ross brilliantly convey this shift without dialogue, their expressions doing all the emotional heavy lifting as they silently ask “What now?” Nichols reported that test audiences initially hated the downbeat ending, wanting a more traditional happy conclusion, but he insisted on maintaining the bittersweet ambiguity that ultimately made the film a cultural touchstone.

6. “Blow-Up” (1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s swinging London mystery ends with photographer Thomas watching a group of mimes playing an imaginary tennis match, eventually hearing the non-existent ball before he himself disappears from the final shot. After spending the entire film obsessing over photographs that may or may not show a murder, Thomas’s acceptance of the imaginary game suggests a profound shift in his understanding of reality and illusion. The final scene deliberately refuses to solve the film’s central mystery, instead questioning the very nature of perception and truth.

Viewers in the mid-1960s were largely unprepared for Antonioni’s philosophical approach, expecting the conventional resolution of a murder mystery rather than an exploration of epistemological uncertainty. The controversial ending established “Blow-Up” as a landmark of art cinema, influencing countless filmmakers to experiment with ambiguous conclusions. Even today, film buffs argue about whether a murder actually occurred or if it was merely Thomas’s fantasy, making the film a perpetual puzzle that refuses easy categorization.

7. “Five Easy Pieces” (1970)

Bob Rafelson’s character study concludes with Jack Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea abandoning his pregnant girlfriend at a gas station and hitching a ride on a logging truck heading to Canada. This abrupt, seemingly callous act caps a film about a man perpetually running from commitment and his own privilege, offering no redemptive arc or moral growth. The final scene’s quiet devastation lies in its suggestion that some people are simply incapable of meaningful connection, trapped in patterns of self-sabotage and emotional avoidance.

Audiences in 1970 were divided over this uncompromising ending, with many expecting the counterculture anti-hero to find some form of resolution or personal breakthrough. Instead, Rafelson and Nicholson present a character study of a man fundamentally broken, unable to reconcile his working-class present with his cultured past. The film’s refusal to provide closure feels particularly honest in retrospect, avoiding the artificial character transformations that Hollywood typically demands and instead showing a man who chooses the uncertainty of the open road over the responsibilities of adult life.

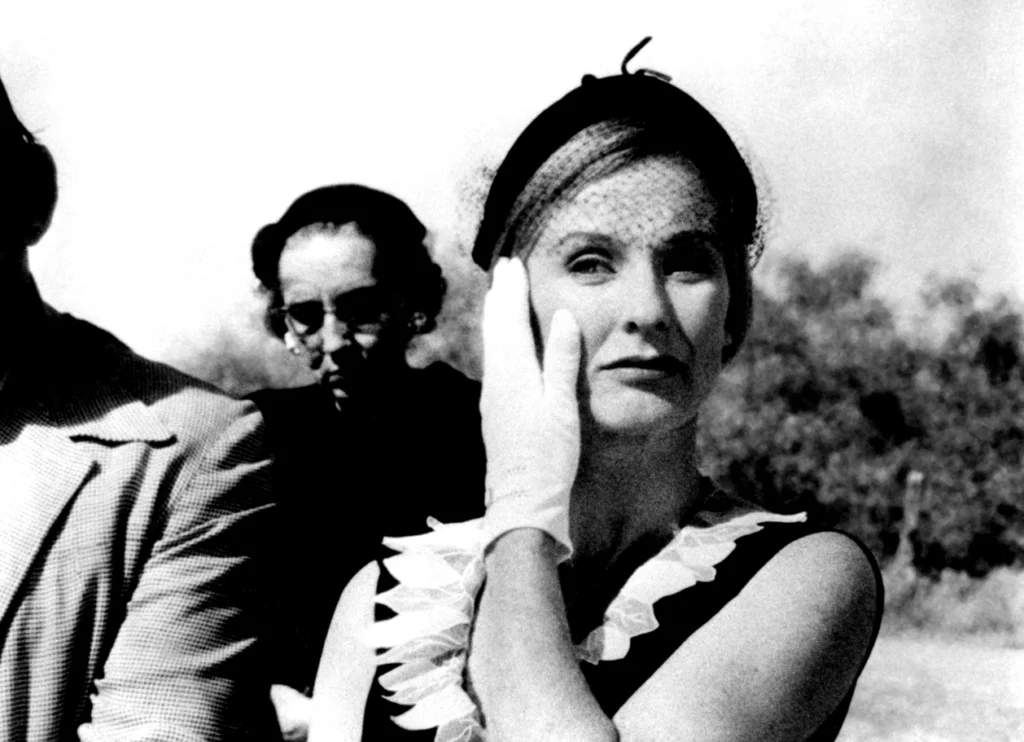

8. “The Wicker Man” (1973)

Robin Hardy’s folk horror classic ends with devout Christian policeman Sergeant Howie being burned alive inside a giant wicker structure as the island’s pagan inhabitants sing cheerfully, celebrating the sacrifice. This shocking conclusion completely upends audience expectations by allowing the protagonist to fail in his mission while revealing that he had been manipulated from the beginning as part of an elaborate trap. The film’s most disturbing implication is that Howie’s Christian righteousness made him the perfect sacrifice according to the islanders’ beliefs – his virginity and moral outrage fulfilling their ritual requirements.

The devastating finale offers no last-minute rescue or moral victory, instead presenting an uncompromising clash between irreconcilable belief systems. Contemporary audiences were disturbed not just by the graphic fate of the protagonist but by the film’s refusal to validate conventional moral frameworks or provide supernatural justice. Original theatrical cuts actually trimmed parts of the ending, as distributors worried viewers couldn’t handle such a bleak conclusion, but the restored version’s unflinching finale has helped establish “The Wicker Man” as one of the most philosophically challenging horror films of its era.

9. “Zabriskie Point” (1970)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s counterculture meditation concludes with an extended sequence of a luxurious desert home exploding repeatedly from multiple angles, followed by household items blowing up in slow motion. This abstract, dialogue-free finale represents one of cinema’s most audacious endings, transforming actual destruction into a form of psychedelic wish-fulfillment fantasy. The hypnotic sequence of consumer goods exploding served as Antonioni’s commentary on materialistic American culture, visualizing the revolutionary impulses of the era through spectacular imagery rather than narrative resolution.

Critics and audiences in 1970 were largely mystified by this experimental conclusion, contributing to the film’s commercial failure despite its substantial budget. The ending’s ambiguity is heightened by uncertainty about whether we’re seeing reality or a character’s imagination, blurring the line between external events and internal desires. Contemporary viewers have increasingly appreciated Antonioni’s visionary finale, recognizing how it captured the explosive tensions of American society at a pivotal historical moment when established institutions and values were being radically questioned.

10. “The Last Picture Show” (1971)

Peter Bogdanovich closes his nostalgic small-town drama with protagonist Sonny reuniting with his older lover Ruth in her darkened bedroom, seeking comfort after his best friend’s death in Korea. The muted, almost uncomfortable reconciliation offers no grand statements or emotional catharsis, instead suggesting that in a dying town with limited options, people inevitably drift back to familiar connections. The film’s final shot of the windswept main street emphasizes the sense of stagnation and decay, with the closed movie theater symbolizing both the end of the characters’ youth and the changing face of rural America.

Audiences expecting a clear resolution to the various romantic entanglements established throughout the film were instead presented with a deliberately anticlimactic conclusion suggesting that life rarely provides satisfying narrative arcs. Bogdanovich’s decision to end with such emotional restraint reflected the influence of European art cinema on the emerging New Hollywood movement of the 1970s. The ending’s power lies precisely in its refusal to offer easy comfort or artificial closure, instead presenting the messy reality of lives continuing after the narrative spotlight has moved on.

11. “Chinatown” (1974)

Roman Polanski’s neo-noir masterpiece concludes with the devastating line “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown,” as detective Jake Gittes fails to save Evelyn Mulwray, who is shot while trying to escape her abusive father. This shockingly bleak ending subverts the detective genre’s usual pattern of the protagonist solving the case and achieving some form of justice. Instead, the powerful simply continue their corruption unabated, with the film’s final moments suggesting that some forms of evil are too entrenched in society to be defeated by individual heroism.

The ending’s nihilistic power comes from screenwriter Robert Towne’s decision to have the villain Noah Cross retain custody of his daughter/granddaughter, implying that the cycle of abuse will continue unchecked. Towne originally wrote a more conventional ending where Evelyn escaped and Cross faced justice, but Polanski, influenced by his own tragic experiences, insisted on the darker conclusion. This creative tension produced one of cinema’s most memorable finales, a perfect distillation of the post-Watergate cynicism that would come to define much of 1970s filmmaking.

12. “Don’t Look Now” (1973)

Nicolas Roeg’s psychological thriller concludes with the shocking revelation that the red-coated figure John has been pursuing through Venice is not his deceased daughter but a murderous dwarf, who kills him in a church. This brutal twist ending transforms what appeared to be a supernatural story about grief into something even more disturbing – a tale about how our desperate desire to make sense of tragedy can lead to fatal misinterpretation. The film’s final sequence intercuts John’s death with the funeral procession of his body along Venice’s canals, creating a disorienting effect that mimics the character’s confusion.

Roeg’s experimental editing throughout the film, which blurs past, present and premonition, makes the ending particularly disorienting as viewers realize that John’s psychic visions were simultaneously accurate yet completely misunderstood. Contemporary audiences were often shocked by the abrupt violence of the conclusion, which offers no spiritual comfort or meaningful closure to the central couple’s grief. The ending’s power comes from its suggestion that the universe may indeed contain mysterious connections and patterns, but our human interpretations of these signs can lead us tragically astray.

13. “The Conversation” (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola concludes his paranoid surveillance thriller with protagonist Harry Caul tearing apart his apartment searching for a listening device that may not exist, before finally playing his saxophone amid the wreckage. This haunting finale shows a man professionally destroyed and personally broken, reduced to playing music in a devastated room after his expertise in invading others’ privacy has been turned against him. The genius of the ending lies in its ambiguity – we never learn if Harry is actually under surveillance or has succumbed to paranoia, mirroring the uncertainty of life during the Watergate era.

The film’s final image of Harry surrounded by destruction of his own making serves as a powerful metaphor for the cost of sacrificing human connection for technical mastery. Coppola shot this ending just as the Watergate scandal was unfolding, unintentionally creating a perfect artistic response to a national moment of disillusionment with authority and institutional power. Gene Hackman’s performance in these closing scenes, conveying terror and resignation without dialogue, provides one of cinema’s most affecting portraits of a man confronting the moral consequences of his life’s work.

The beauty of these cinematic puzzles is that they continue to generate discussion and interpretation half a century later. Unlike today’s films that often explain everything to the last detail, these classics trusted us to think for ourselves, to sit with uncertainty and draw our own conclusions. Perhaps that’s why we keep returning to them, hoping to finally crack their codes while secretly delighting in their mysteries. Next time you’re feeling nostalgic for an era when movies didn’t tie everything up in a neat bow, revisit one of these thought-provoking classics – and prepare to leave still scratching your head.