1. Peeping Tom (1960)

Long before the slasher genre became a household staple, Michael Powell delivered this unsettling psychological thriller that essentially birthed the trope of the voyeuristic killer. It follows a lonely cameraman who films his victims’ dying expressions, forcing the audience to watch through his lens. This perspective shift was revolutionary because it made the viewer a reluctant accomplice in the crimes. While it was initially loathed by critics, its DNA is found in every POV horror sequence from Halloween to The Blair Witch Project.

The film’s influence extends far beyond simple jump scares, touching on the dark psychology of cinema itself. It explored the idea that watching can be a form of violation, a theme later perfected by directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Brian De Palma. By humanizing a monster, Powell paved the way for the complex anti-heroes and sympathetic villains that dominate modern storytelling. Today, it stands as a masterclass in building tension through technical innovation rather than just gore.

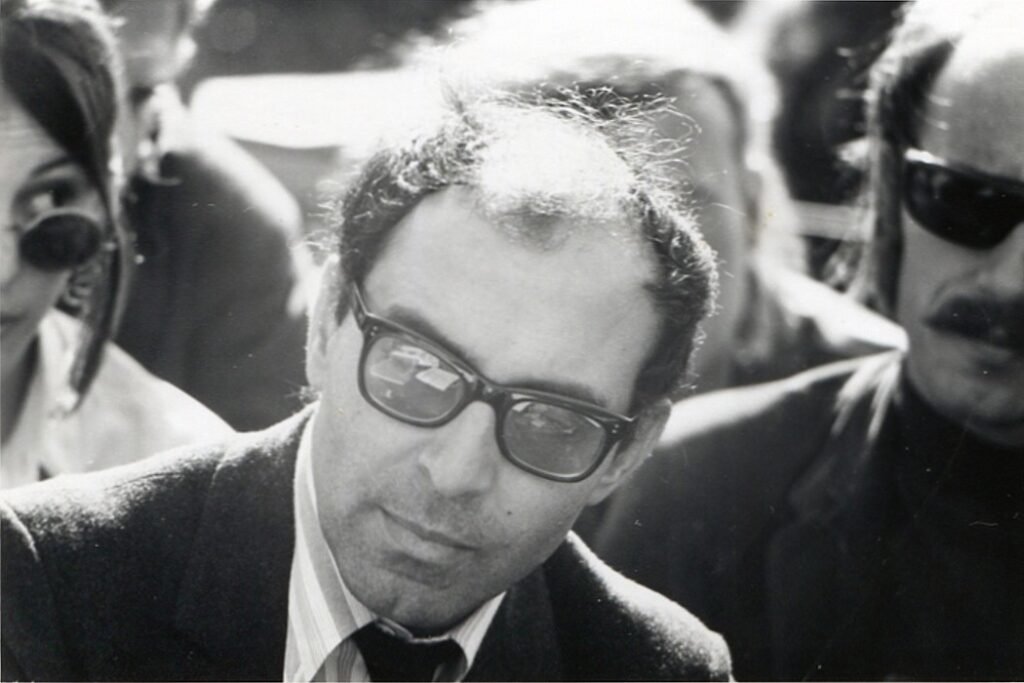

2. Breathless (1960)

Jean-Luc Godard didn’t just make a movie; he broke the existing rules of filmmaking and threw the pieces at the audience. Breathless introduced the world to the jump cut, a technique that felt like a mistake at the time but now defines the rhythm of modern music videos and social media content. The story is a loose, improvisational take on American noir, featuring a cool criminal and his American girlfriend wandering through Paris. It felt alive, spontaneous, and dangerously cool to a generation of bored cinemagoers.

This film single-handedly launched the French New Wave, proving that you didn’t need a massive studio budget to create something iconic. Every indie filmmaker who has ever picked up a handheld camera owes a debt to Godard’s kinetic energy and lack of formal polish. It taught future directors that style could be just as important as substance, if not more so. Without this radical experiment, the gritty, street-level realism of 1970s Hollywood might never have found its voice.

3. L’Avventura (1960)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s masterpiece is famous for a mystery that it never bothers to solve, which was a radical departure from traditional narrative. When a woman disappears during a Mediterranean boating trip, the film stops focusing on the search and starts examining the hollow lives of her friends. This shift from “what happened” to “how do they feel” changed the way we think about cinematic pacing and structure. It proved that silence and landscape could be just as expressive as dialogue or action.

The existential boredom depicted here became a cornerstone for modern art-house cinema and slow-burning television dramas. You can see its fingerprints on everything from Lost to the works of Sofia Coppola, where the atmosphere carries more weight than the plot. By refusing to give the audience closure, Antonioni respected their intelligence and sparked endless debate. It remains a haunting reminder that some of life’s most profound moments occur in the gaps between the action.

4. Eyes Without a Face (1960)

This French horror film is a poetic, surgical nightmare that feels remarkably modern despite its age. It tells the story of an obsessed scientist trying to restore his daughter’s disfigured face through gruesome skin grafts. The imagery is strikingly beautiful yet deeply disturbing, blending fairy-tale aesthetics with cold, clinical horror. It’s the kind of movie that lingers in your mind long after the credits roll because of its haunting mask and ethereal tone.

Its impact is felt in the body horror subgenre, influencing legends like John Carpenter and Pedro Almodóvar. The blank, white mask worn by the daughter became the visual blueprint for Michael Myers, proving that a lack of expression is often scarier than a screaming face. Beyond the visuals, the film’s exploration of identity and obsession resonates in contemporary thrillers about medical ethics and vanity. It is a rare example of a horror movie that is as heartbreaking as it is terrifying.

5. Yojimbo (1961)

Akira Kurosawa’s tale of a cynical, nameless samurai playing two rival gangs against each other is the ultimate “man with no name” blueprint. It combined high-stakes action with a dry, dark humor that felt entirely fresh for the period. Toshiro Mifune’s performance created the archetype of the weary professional who is smarter and faster than everyone else in the room. The film’s visual style, with its deep focus and wide-screen compositions, set a new standard for action choreography.

Without Yojimbo, the Spaghetti Western genre wouldn’t exist in the way we know it, as Sergio Leone famously remade it as A Fistful of Dollars. The DNA of the wandering anti-hero has since spread into every corner of pop culture, from Mad Max to The Mandalorian. It taught creators how to use a protagonist who says very little but does a great deal. The film’s cynical worldview and sharp editing continue to influence how we frame cinematic conflict today.

6. Last Year at Marienbad (1961)

If you’ve ever watched a movie that felt like a beautiful, confusing dream where time and space don’t quite make sense, you can thank Alain Resnais. This film is a labyrinth of memory and suggestion, set in a lavish hotel where a man tries to convince a woman they met the year before. It ignores linear time completely, looping back on itself and repeating scenes with slight variations. It was a bold experiment in how the human mind perceives the past and the present simultaneously.

This dreamlike structure became a massive influence on directors like David Lynch and Christopher Nolan. Elements of its surrealist logic can be found in Inception and Mulholland Drive, where the setting itself feels alive and deceptive. By stripping away the traditional beginning, middle, and end, Resnais opened the door for abstract storytelling in mainstream media. It remains a polarizing but essential piece of cinema that challenges the viewer to find their own meaning.

7. The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

Released at the height of the Cold War, this political thriller introduced the terrifying concept of the sleeper agent to the public consciousness. It masterfully blended paranoid suspense with a touch of the surreal, creating a feeling of unease that reflected the anxieties of the era. The idea that someone’s mind could be programmed to commit an unspeakable act without their knowledge was a game-changer for the genre. It was both a sharp satire and a bone-chilling look at the power of brainwashing and propaganda.

The film’s influence on the modern conspiracy thriller cannot be overstated, paving the way for everything from The Bourne Identity to Homeland. It established a visual language for paranoia, using distorted angles and jarring edits to mirror the protagonist’s fractured mental state. Even today, the phrase “Manchurian Candidate” is used in real-world political discourse to describe someone working for a hidden power. Its legacy is a testament to how fiction can tap into deep-seated cultural fears and give them a permanent name.

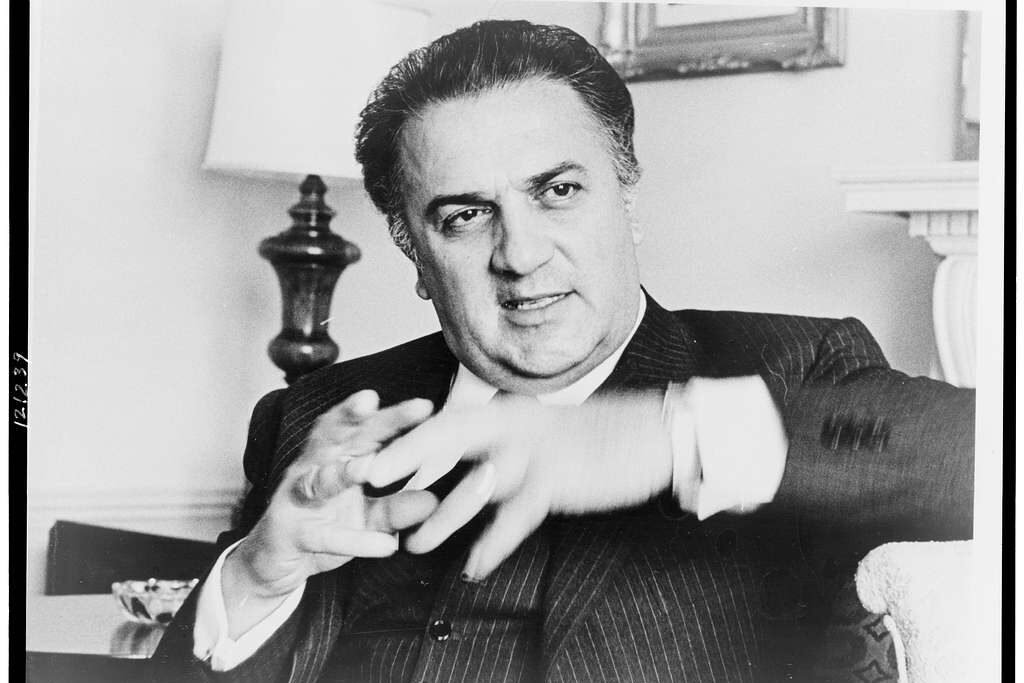

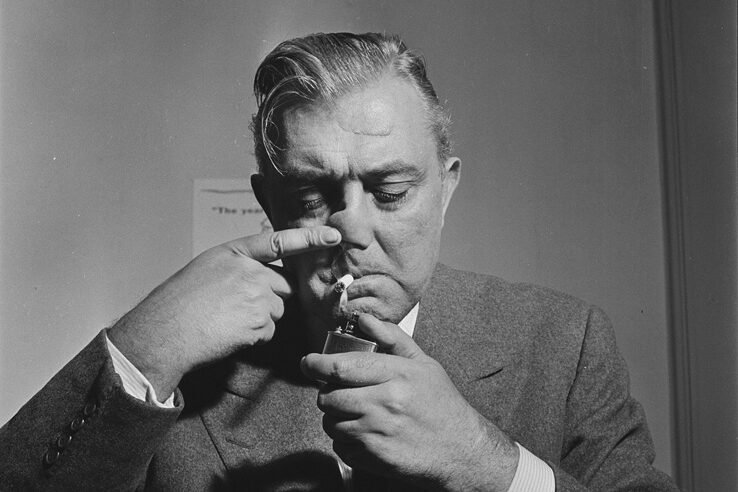

8. 8½ (1963)

Federico Fellini’s self-reflexive masterpiece is essentially a movie about a director who can’t figure out how to make his next movie. It blurred the lines between reality, memory, and fantasy in a way that had never been seen on such a grand scale. By making the creative process the central conflict, Fellini gave filmmakers permission to be personal and indulgent. The film is a visual circus, filled with iconic imagery and a sense of whimsy that masks a deeper artistic crisis.

This meta approach to storytelling has been echoed by countless directors, from Woody Allen to Wes Anderson. It transformed the role of the director from a mere craftsman into a visionary artist whose internal life was worthy of exploration. Whenever you see a film that breaks the fourth wall or explores the subconscious of its protagonist, you’re seeing the ripples of 8½. It remains the ultimate love letter to the chaos and beauty of the filmmaking process itself.

9. Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Stanley Kubrick took the very real threat of nuclear annihilation and turned it into the funniest, darkest comedy ever made. By leaning into the absurdity of bureaucracy and war, he managed to say more about the human condition than any serious drama could. The film features Peter Sellers in three different roles, showcasing a level of comedic versatility that became a benchmark for character acting. It suggested that the end of the world wouldn’t be brought about by malice, but by sheer stupidity and ego.

The black comedy genre as we know it owes its existence to the success of this brave, cynical satire. It gave permission to future satirists to find humor in the darkest possible subjects, leading to shows like Veep or Succession. Kubrick’s meticulous visual style and use of iconic sets, like the War Room, have become permanent fixtures in our visual lexicon. It proved that sometimes the only way to deal with a terrifying reality is to laugh directly in its face.

10. The Battle of Algiers (1966)

This film is so realistic that many viewers originally thought it was a documentary or newsreel footage. Gillo Pontecorvo used non-professional actors and grainy film stock to recreate the Algerian struggle for independence from France. It was a revolutionary way to depict urban warfare, focusing on the tactics and desperation of both sides without leaning into easy heroism. The result is a visceral, immersive experience that feels like you are witnessing history unfold in real-time.

Its impact on the shaky cam aesthetic and political cinema is profound, influencing directors like Paul Greengrass and Steven Spielberg. It is famously studied by both insurgent groups and military organizations for its accurate portrayal of guerrilla tactics and counter-terrorism. By humanizing the mechanics of revolution, it changed how we consume stories about conflict and social change. Even decades later, it remains the gold standard for blending cinematic artistry with raw, political urgency.

11. Playtime (1967)

Jacques Tati’s comedy is a towering achievement of set design and visual gag-telling that feels light-years ahead of its time. He built a massive, hyper-modern version of Paris to poke fun at the coldness and confusion of modern architecture. The film has almost no dialogue, relying instead on intricately choreographed background details and sound effects to tell its story. It’s a movie where the environment is the main character, and the human beings are just wandering through its maze.

This meticulous attention to detail and love for living sets can be seen in the works of modern directors like Wes Anderson. Tati proved that comedy could be sophisticated, silent, and visually breathtaking all at once. It’s a film that requires multiple viewings because there is always something happening in the corner of the frame that you missed. Playtime remains a whimsical yet biting critique of how the modern world can often alienate the very people it was built for.

12. The Graduate (1967)

This film captured a specific sense of youthful aimlessness and post-college dread that had never been articulated so perfectly. Dustin Hoffman’s awkward, sincere performance broke the mold of the traditional leading man and gave a voice to a generation feeling alienated. The use of a contemporary folk-rock soundtrack by Simon & Garfunkel was also a revolutionary move that changed how music was used in movies. It wasn’t just background noise; it was the emotional heartbeat of the story.

The coming-of-age genre was forever altered by Mike Nichols’ clever use of framing and dry humor. It moved cinema away from the polished studio look toward a more intimate, relatable style of storytelling. Every indie movie about a confused twenty-something trying to find themselves is essentially a descendant of Benjamin Braddock’s summer in the pool. It remains a definitive cultural touchstone for anyone who has ever felt like they were drifting through their own life.

13. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

George A. Romero didn’t just make a scary movie; he invented the modern zombie as we know it today. Before this, zombies were usually tied to Voodoo or mind control, but Romero turned them into a mindless, cannibalistic force of nature. By casting a Black man as the lead and ending the film on a devastatingly bleak note, he also infused the horror genre with sharp social commentary. It was a low-budget masterpiece that proved horror could be both terrifying and intellectually provocative.

The ripple effects of this film are everywhere, from The Walking Dead to the entire survival horror video game industry. It established the rules of the genre—the headshot, the boarded-up house, the breakdown of social order—that are still used today. Romero showed that the real monsters aren’t always the creatures outside, but the people inside who can’t stop fighting each other. It transformed horror from a niche interest into a powerful tool for reflecting the tensions of the real world.