The 1960s produced some of the most emotionally stirring music ever recorded. In an era of profound social change, musical innovation, and artistic exploration, performers and songwriters created works that continue to move listeners decades later. These songs transcend their time, carrying emotional weight that hits us just as powerfully today as when they first played on transistor radios and jukeboxes across America. Whether through haunting vocals, groundbreaking production, profound lyrics, or spine-tingling instrumental moments, these tracks have an almost supernatural ability to raise goosebumps on our arms with each listen.

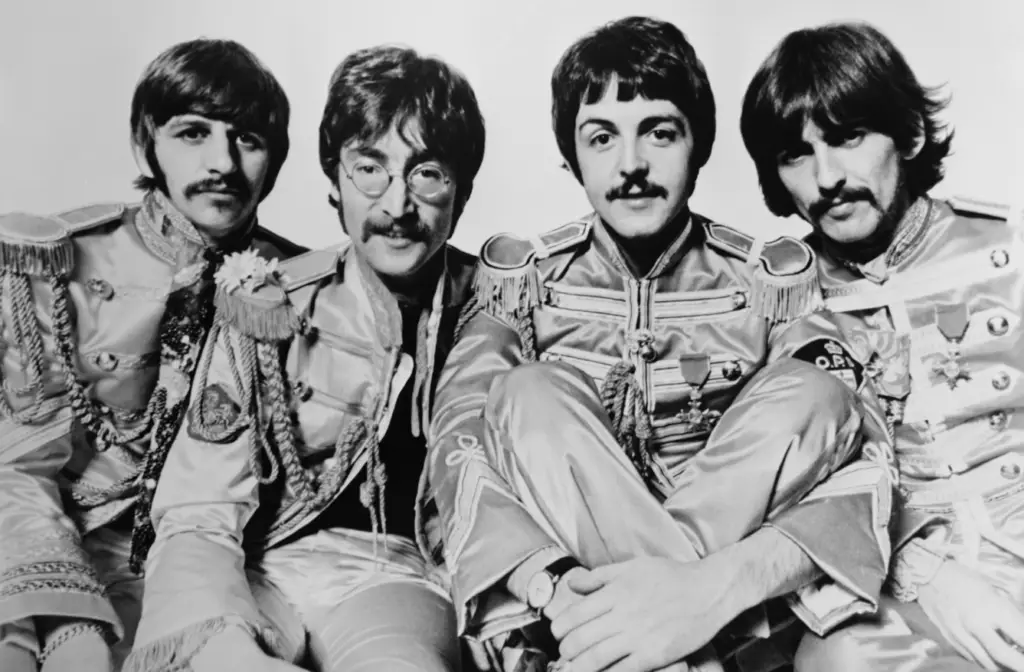

1. “A Day in the Life” – The Beatles (1967)

The epic conclusion to “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” remains one of the most ambitious and emotionally affecting songs in rock history. Beginning with John Lennon’s detached observations of everyday news stories, the track transitions through Paul McCartney’s energetic middle section before culminating in that infamous orchestral crescendo – a musical representation of chaos that builds to an almost unbearable intensity before resolving in a single, sustaining piano chord that seems to hang in the air forever. Producer George Martin’s innovative use of a 40-piece orchestra, instructed to play from their lowest note to their highest over 24 bars, created what engineer Geoff Emerick called “a musical orgasm” that still raises goosebumps even after countless listens. Fans may have the lyrics memorized, but Rolling Stone has a list of some surprising facts even the most devoted fan might not know, oh the irony.

The contrasting sections perfectly capture the disorienting nature of the 1960s, with Lennon’s verses representing the mundane colliding with the extraordinary, while McCartney’s segment depicts the routine of daily life. That final E-major chord, played simultaneously on three pianos and held for over 40 seconds while the studio’s recording levels were gradually increased, creates a sonic effect that producer Rick Rubin has called “the sound of the universe opening up.” More than half a century later, no song better encapsulates the experimental spirit of the 1960s while still delivering an emotional punch that transcends its technical innovations to reach something profoundly human in its examination of disconnection and existential wonder.

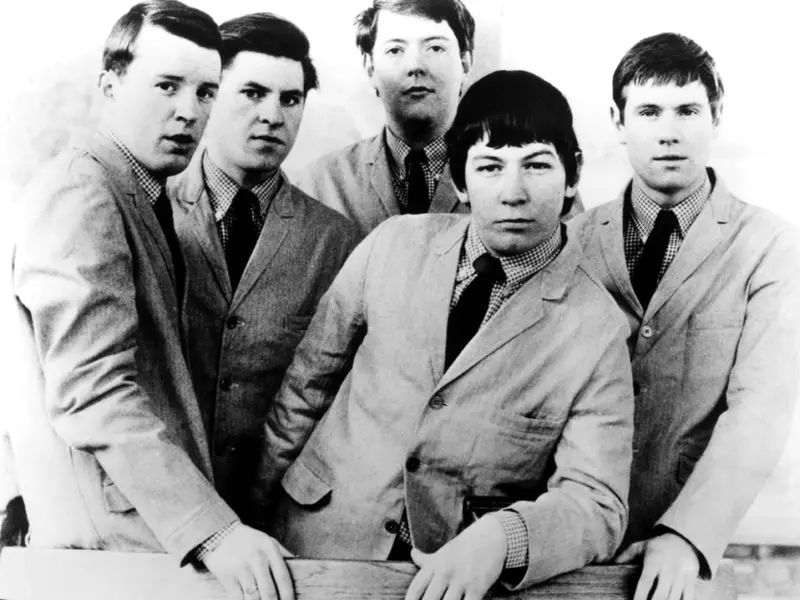

2. “God Only Knows” – The Beach Boys (1966)

Opening with the then-shocking line, “I may not always love you,” Brian Wilson’s masterpiece of baroque pop creates an immediate emotional vulnerability that sets the stage for one of music’s most beautiful declarations of devotion. Carl Wilson’s tender lead vocal conveys both fragility and certainty, while the innovative arrangement—featuring French horn, accordions, sleigh bells, and complex vocal harmonies—creates a swirling, dream-like atmosphere that somehow enhances rather than distracts from the song’s emotional directness. Producer Tony Asher later recalled that the unconventional opening line was deliberately chosen to create “a level of honesty that made the love being professed more genuine.” Far Out Magazine gives special shoutout to this track as the band’s ultimate lovesong.

The song’s intricate vocal round in the final section, where multiple vocal parts weave around each other in counterpoint, creates a feeling of emotional infinity that perfectly matches the lyrical sentiment about love’s immeasurable depth. Paul McCartney has repeatedly cited “God Only Knows” as his favorite song of all time, noting that “it’s a really, really perfect song” that somehow manages to be both avant-garde and immediately emotionally accessible. Its appearance in the opening sequence of “Love Actually” and countless emotional film moments speaks to its enduring ability to convey love’s complexity through just under three minutes of perfect pop craftsmanship that still raises goosebumps with its delicate emotional precision.

3. “A Change Is Gonna Come” – Sam Cooke (1964)

Written after Cooke was turned away from a whites-only motel in Louisiana, this civil rights anthem transmutes personal humiliation into universal hope with a dignity and restraint that makes its emotional impact all the more devastating. Released posthumously after Cooke’s tragic death, the song’s soaring strings, mournful french horn, and gospel-influenced vocal performance create a perfect setting for lyrics that acknowledge suffering while insisting on the possibility of change. Music historian Peter Guralnick noted that the song represented Cooke’s “most overt political statement” in a career otherwise dominated by lighter love songs and pop hits, making its emotional gravitas all the more striking. For how well-known and powerful this song remains, The New Yorker writes that the story behind it is as unlikely as they come.

The song’s power lies in how Cooke’s voice contains both weariness and determination, particularly in the heartbreaking third verse where he sings of being “afraid to die” before moving toward the cautiously optimistic chorus. When Cooke sings “It’s been a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come,” his voice carries the weight of centuries of struggle while somehow maintaining an unshakable faith in eventual justice. Barack Obama referenced the song in his 2008 election victory speech, and its use in films like “Malcolm X” and “Selma” confirms its status as not just an artifact of the civil rights movement but an evergreen expression of hope against overwhelming odds that still raises goosebumps in its perfect marriage of personal and political yearning.

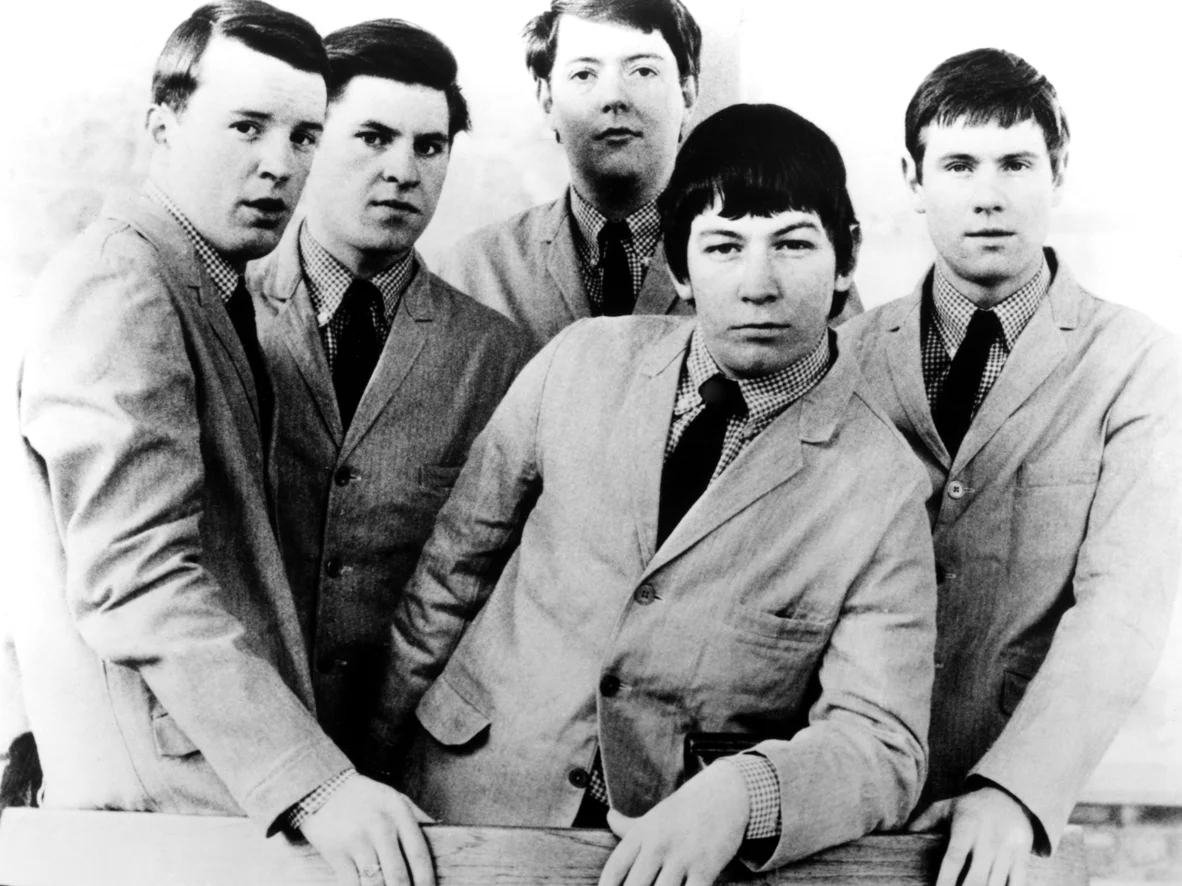

4. “House of the Rising Sun” – The Animals (1964)

This ancient folk song about ruin and regret received its definitive treatment when British invasion group The Animals transformed it into a haunting gothic epic driven by Eric Burdon’s world-weary vocals and Alan Price’s hypnotic organ arpeggios. The song builds with an inexorable momentum that mirrors its tale of downward spiral, with each verse growing more intense until Burdon’s guttural cry in the final chorus. Producer Mickie Most achieved the song’s distinctive sound by recording it live in just one take, capturing the band’s raw energy and the tension of Burdon’s vocal performance, which moves from restraint to barely controlled anguish.

The song’s ambiguous narrator—sometimes interpreted as a woman trapped in prostitution, other times as a male gambler or drunkard—creates a universal quality that speaks to human frailty and regret across circumstances and generations. Burdon’s vocal performance is particularly goosebump-inducing during the line “Oh mother, tell your children not to do what I have done,” where his voice cracks with authentic emotion that transcends mere performance. Bob Dylan, whose folk arrangement inspired The Animals’ version, reportedly stopped performing the song after hearing their definitive interpretation, acknowledging that they had captured something primal and unchangeable about human suffering that continues to raise goosebumps more than five decades later.

5. “Gimme Shelter” – The Rolling Stones (1969)

Opening with Keith Richards’ ominous guitar figure emerging as if from a gathering storm, “Gimme Shelter” captures the darkness and violence that had overtaken the idealistic promises of the 1960s. The song’s apocalyptic atmosphere—punctuated by Merry Clayton’s extraordinary backing vocal that reportedly caused Mick Jagger to exclaim “bloody hell!” during the recording session—creates a sonic landscape of threat and urgency that remains unnervingly relevant. Richards later explained that the song came to him during a literal storm, saying “I just sat there and observed the weather” before turning nature’s violence into a metaphor for social collapse.

The song reaches its goosebump-inducing climax during Clayton’s solo section, where her voice famously cracks on the word “murder” in a moment of such raw emotion that it was left in the final mix despite being technically imperfect. Director Martin Scorsese has used the track repeatedly in his films, recognizing its ability to instantly create an atmosphere of impending chaos and moral ambiguity. More than fifty years after its release, the song’s warning that “war, children, is just a shot away” retains its chilling power, particularly in Clayton’s spine-tingling delivery that music critic Greil Marcus described as “the sound of a world breaking apart,” a moment that raises goosebumps with each listen through its perfect fusion of message and messenger.

6. “The Sound of Silence” – Simon & Garfunkel (1965)

Originally released as an acoustic ballad to little attention, the song gained its iconic status and haunting power when producer Tom Wilson secretly added electric instruments to create the version that would become a surprise hit. Paul Simon’s lyrics about alienation and failed communication—written in the aftermath of JFK’s assassination—gained new resonance through Art Garfunkel’s ethereal harmonies and the song’s enhanced dramatic arrangement. The duo reportedly discovered the reworked version when they heard it on the radio, with Simon later admitting that Wilson’s additions brought out emotional dimensions in the song that hadn’t been fully realized in their spare original recording.

The song’s opening line—”Hello darkness, my old friend”—has become a cultural touchstone, perfectly capturing a certain kind of introspective melancholy that transcends its original 1960s context. The goosebump-inducing moment comes during the final verse, as the dynamics build and Garfunkel’s voice soars over Simon’s on the words “the words of the prophets are written on the subway walls,” creating a near-religious intensity that transforms urban graffiti into profound wisdom. Its continuing cultural relevance—from its poignant use in “The Graduate” to its revival through covers by Disturbed and countless others—speaks to how perfectly it captures the universal human experience of feeling isolated even when surrounded by others, a sensation that raises goosebumps in its painful familiarity.

7. “Strange Fruit” – Nina Simone (1965)

Although originally recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939, Nina Simone’s 1965 version brought this harrowing protest against lynching to a new generation during the height of the civil rights movement. Simone’s interpretation is a masterclass in controlled fury, her classically trained voice navigating the song’s gruesome imagery with a precision that makes its horror all the more affecting. The sparse arrangement—featuring just piano, bass, and drums—creates negative space around Simone’s voice, forcing listeners to confront lyrics that transform the pastoral imagery of the American South into a landscape of racial terror.

The most goosebump-inducing moment comes in Simone’s delivery of the line “for the sun to rot, for the tree to drop,” where her voice takes on an almost ritualistic quality, as if summoning judgment for the crimes described. Simone’s biographer noted that performing the song took an enormous emotional toll on her, requiring her to access rage and grief that would leave her emotionally drained. The song gained renewed attention following the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, with critics noting how sadly relevant its imagery remains despite being written over 80 years ago, a testament to both its artistic power and America’s unresolved racial trauma that still raises goosebumps through Simone’s unflinching performance.

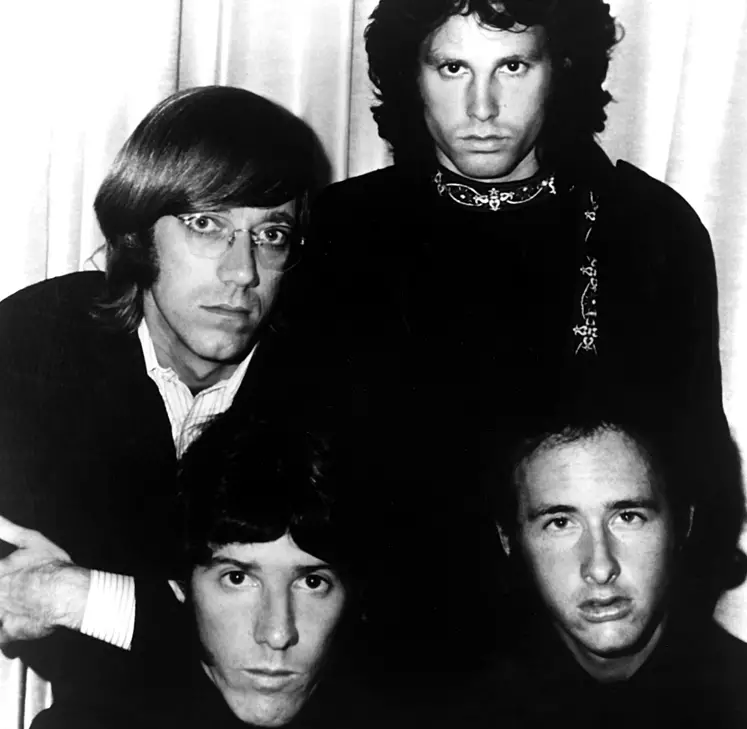

8. “The End” – The Doors (1967)

Jim Morrison’s Oedipal epic closes The Doors’ debut album with a theatrical journey through the subconscious that still retains its power to disturb and mesmerize. Beginning as a seemingly simple breakup song before spiraling into something far more primal, the track showcases the band’s jazz-influenced instrumental interplay while giving Morrison the space to transform from rock singer to shamanic poet. Keyboardist Ray Manzarek later described the recording session as a trance-like experience, with the band following Morrison’s improvised vocals through increasingly dark psychological territory during the song’s 11-minute duration.

The infamous “Father… Mother” section, with its shocking patricide and incest narrative, creates a deliberately uncomfortable confrontation with Freudian themes that caused the song to be banned from radio. Yet the song’s most goosebump-inducing moment may be Morrison’s repeated whispers of “This is the end,” which create an atmosphere of ritual finality that transcends the actual lyrics. Francis Ford Coppola’s use of the song in the opening sequence of “Apocalypse Now” cemented its status as the ultimate soundtrack to psychological disintegration, while its continued popularity among successive generations speaks to how perfectly it captures adolescent confrontation with mortality, sexuality, and authority in a sonic journey that still raises goosebumps through its dark theatrical power.

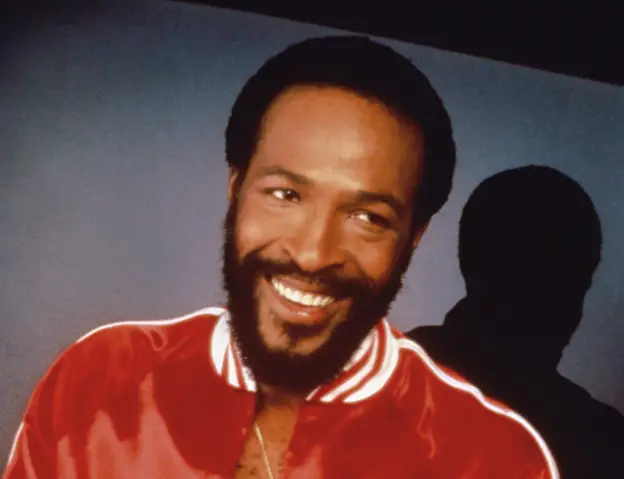

9. “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” – Marvin Gaye (1968)

Gaye transformed Gladys Knight’s already-hit version of this song into something far more haunting through his tense, paranoid vocal performance and the song’s innovative arrangement featuring a hypnotic bassline, insistent percussion, and plaintive strings. The track’s power lies in how it turns a simple story of infidelity into an exploration of existential dread, with Gaye’s multi-layered vocals conveying both vulnerability and simmering rage. Motown’s house band, the Funk Brothers, created the song’s distinctive tension through what drummer Benny Benjamin called “playing so tight it hurts,” creating a coiled musical spring that never fully releases.

The goosebump-inducing climax occurs when Gaye’s voice jumps to falsetto on the line “I know that you’re letting me go,” combining romantic desperation with a spiritual anguish that transcends the ostensible subject matter. Producer Norman Whitfield reportedly pushed Gaye through 21 takes to achieve the perfect balance of control and emotional breakdown that makes the final version so affecting. Its use in films from “The Big Chill” to “Crooklyn” demonstrates how perfectly the song captures a particular kind of painful awakening to unwelcome truth, while its steady presence on classic radio formats speaks to how Gaye’s emotional authenticity continues to raise goosebumps across generations through its perfect marriage of polished production and raw human emotion.

10. “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” – Otis Redding (1968)

Recorded just days before Redding’s death in a plane crash, this contemplative departure from his usual high-energy style captures a moment of transition that became tragically permanent. The song’s gentle guitar, lapping waves, and melancholy whistled outro create a sonic snapshot of a man at a crossroads, looking back on his journey while facing an uncertain future. Producer Steve Cropper, who co-wrote the song with Redding, completed the track after Redding’s death, making decisions that honored what he believed were the singer’s intentions, including keeping the now-famous whistling section that was reportedly just a placeholder for lyrics Redding hadn’t yet written.

The most goosebump-inducing element may be the contrast between the song’s peaceful atmosphere and the knowledge of Redding’s fate, creating a poignant dramatic irony as he sings “I left my home in Georgia, headed for the Frisco Bay” knowing that his journey to San Francisco would be his last. Music historian Ashley Kahn noted that the song represented “the birth of the new Otis Redding” that listeners would never get to fully experience, making its wistful quality all the more affecting. Its Grammy wins and continuing popularity speak to how perfectly it captures a universal moment of reflection between life chapters, raising goosebumps through the combination of artistic evolution and biographical poignancy that makes it impossible to hear without contemplating life’s fragility.

11. “When a Man Loves a Woman” – Percy Sledge (1966)

Sledge’s raw, gospel-influenced performance transforms a simple love song into an almost religious experience of devotion and vulnerability. Legend has it that the song was largely improvised in the studio, with Sledge adapting a melody he used to sing in the fields as a young man working as a hospital orderly before fame found him. The unpolished quality of both the performance and production—including slightly out-of-tune horns that somehow enhance rather than detract from the emotional impact—creates an authenticity that more technically perfect recordings often lack. Producer Quin Ivy later recalled that “Percy sang it like his life depended on it” during the session, a quality immediately apparent to anyone who hears the record.

The goosebump-inducing climax comes during the bridge, where Sledge’s voice transforms from passionate to nearly desperate as he sings “Baby, please don’t treat me bad,” a plea that contains all the vulnerability and fear that accompanies complete surrender to another person. Music journalist Dave Marsh described the performance as “a soul symphony where longing becomes transcendent,” noting how Sledge’s vocal makes the potentially self-destructive nature of all-consuming love feel like spiritual elevation. Its countless covers, film appearances, and enduring popularity at weddings demonstrate how perfectly it captures a universal experience of complete devotion that still raises goosebumps through Sledge’s unguarded emotional commitment to every note.

12. “Both Sides Now” – Joni Mitchell (1969)

Mitchell’s philosophical meditation on perspective and the passage of time showcases both her innovative open-tuning guitar work and lyrics that display a wisdom far beyond her 26 years. The song’s structure—examining clouds, love, and life from shifting perspectives—creates a journey from youthful certainty to mature ambiguity that Mitchell would later revisit in her acclaimed 2000 orchestral version. Mitchell has said the song was inspired by reading Saul Bellow’s “Henderson the Rain King” while on an airplane, looking down at clouds and considering how different they looked from above than from below, a metaphor that expanded into one of popular music’s most profound examinations of how experience changes perception.

The goosebump-inducing moment comes in the final verse’s shift from the previous pattern, when Mitchell sings “I’ve looked at life from both sides now,” elevating the song from clever observation to genuine epiphany. Folk singer Judy Collins, whose version of the song became a hit before Mitchell released her own recording, described it as “a song that changed my life” through its perfect balance of intellectual insight and emotional resonance. Its continued relevance—appearing in contexts from “Love Actually” to the opening ceremony of the 2010 Winter Olympics—speaks to how perfectly it captures the universal experience of realizing that growing older means accepting complexity rather than achieving certainty, a bittersweet recognition that still raises goosebumps through Mitchell’s poetic articulation of life’s fundamental mystery.

13. “Space Oddity” – David Bowie (1969)

Released five days before the Apollo 11 moon landing, Bowie’s breakthrough hit uses space exploration as a metaphor for isolation and disconnect, creating a cinematic audio experience through innovative production techniques and Bowie’s theatrical vocal performance. The song’s structure mirrors Major Tom’s journey—from confident mission launch to the wonder of space walking to the horror of disconnection—taking listeners through a complete emotional arc in just over five minutes. Producer Gus Dudgeon created the song’s distinctive otherworldly atmosphere through stylophone, mellotron, and strategic use of acoustic guitar to ground the more experimental elements, creating what music critic Charles Shaar Murray called “science fiction folk music.”

The most goosebump-inducing sequence occurs during the astronaut’s space walk, as strings swell and Bowie’s voice floats ethereally on the words “Planet Earth is blue, and there’s nothing I can do,” capturing both the beauty of transcendent experience and the terror of disconnection. The communication breakdown that follows—with ground control unable to reach Major Tom as he drifts into space—became an eerily prescient metaphor for the collapse of 1960s utopianism as the decade ended. Its use in countless films and continuing cultural references—from real astronauts performing it aboard the International Space Station to its appearance in “The Martian”—speaks to how perfectly it captures both the wonder and terror of human advancement, raising goosebumps through its prescient contemplation of technology’s potential to both elevate and isolate us.

These thirteen songs represent just a fraction of the 1960s’ extraordinary musical legacy, but each continues to create that unmistakable physical response—that shiver, that prickle of raised hair on our arms—that signals we’re in the presence of something that transcends mere entertainment. In their emotional authenticity, technical innovation, cultural significance, and sheer beauty, these recordings demonstrate how the best art remains forever contemporary, speaking to each new generation with undiminished power. Whether through technical innovation, lyrical depth, vocal performance, or some ineffable combination of elements that can never be fully analyzed, these songs continue to move us physically and emotionally, proving that while the 1960s may be long past, its greatest musical achievements remain eternally present.