Long before high-definition televisions and livestreams, families across America and around the world gathered around small black-and-white television sets to witness humanity’s greatest technological achievement. On July 20, 1969, as Neil Armstrong took that historic first step onto the lunar surface, the grainy images beaming back to Earth created an experience utterly unlike anything we know today. For those who experienced this moment through the limited technology of the era, the moon landing wasn’t just a historical event—it was a shared emotional journey filtered through static, rabbit ears, and the distinctive glow of cathode ray tubes. Here’s what it was like to experience that monumental moment through the technological limitations and unique viewing culture of 1969.

1. The Gathering of the Households

In neighborhoods across America, the moon landing created impromptu community viewings as families with better television reception invited friends, neighbors, and sometimes complete strangers into their living rooms. Many households still didn’t own televisions in 1969, while others had sets with such poor reception that the already-grainy lunar broadcast would be completely unwatchable. This technological limitation transformed the viewing experience into a deeply social one, with living rooms packed beyond capacity and children sitting cross-legged on floors while adults perched on armrests or stood in doorways. The National Air and Space Museum confirms that Americans made sure to gather their families around the TV with time to spare that fateful day.

The shared viewing experience created a unique atmosphere of collective anticipation and wonder, as people who might normally exchange nothing more than polite greetings found themselves whispering observations and speculations to each other during broadcast pauses. Hosts became impromptu mission controllers, adjusting antenna positions while guests held rabbit ears at precise angles to maintain the clearest possible picture. For many Americans, the memory of the moon landing remains inextricably linked to whose living room they were in, what their neighbor whispered at the critical moment, and how it felt to experience history shoulder-to-shoulder with their community.

2. The Marathon Viewing Session

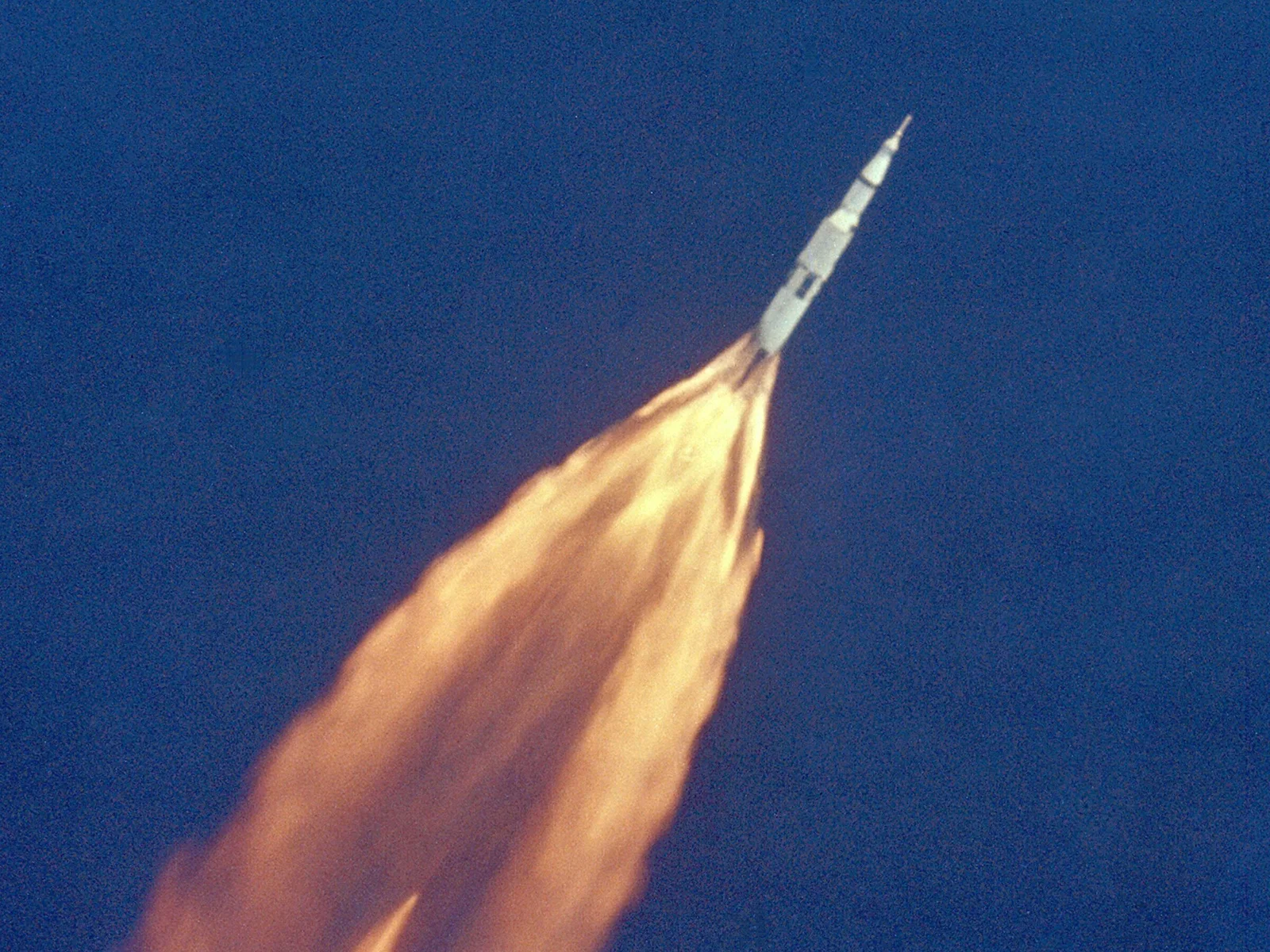

Unlike today’s highlight-reel culture, watching the Apollo 11 mission was an endurance event that stretched over days, with families structuring their entire weekend around the broadcast schedule. The most dedicated viewers had been watching since the July 16th launch, following along with every mission update and spacecraft maneuver through hours of technical commentary and periods where nothing visibly happened. By the time the lunar module touched down on Sunday, July 20th, many viewers had invested dozens of hours in watching the mission unfold, creating an emotional investment unlike any viewing experience before or since. While footage played repeatedly, the Los Angeles Times explores the logistics of repeating the actual flight in today’s world.

The actual moonwalk didn’t begin until nearly 11 p.m. Eastern Time, well past many children’s bedtimes on a Sunday night before a work week, yet parents across America suspended normal rules. Children who were normally strictly regulated in their television consumption were encouraged to stay awake, with makeshift sleeping arrangements of pillows and blankets created in living rooms so families could maintain their vigil without missing a moment. This suspension of ordinary household routines contributed to the sense that something extraordinary was happening—a moment important enough to upend the normal structure of daily life.

3. The Ritual of Television Preparation

Watching the moon landing meant engaging in elaborate technical preparations that modern viewers never experience—ritual adjustments to ensure the best possible reception for the historic moment. Families spent hours adjusting internal fine-tuning knobs, external antenna positions, and sometimes resorted to covering portions of their television sets with aluminum foil to improve signal reception. The frustrating technical limitations became part of the viewing experience, with fathers often appointed as the household’s technical specialists, making minute adjustments while everyone else evaluated picture clarity. Astronomy Magazine flies further to share just how NASA brought color to this historic footage of this historic day.

The physical television set itself required warming up, with many families turning on their sets hours before the moonwalk to ensure everything was working properly and the vacuum tubes had reached stable operating temperature. Unlike modern televisions with their instant-on convenience, these early sets created distinctive sensory experiences—the high-pitched electronic whine as they powered up, the static electricity that made the screen dust-magnetic, and the particular smell of warming electrical components. These sensory elements created a viewing atmosphere charged with anticipation, as the technology itself seemed to be preparing for something momentous.

4. The Grainy, Ghostly Lunar Images

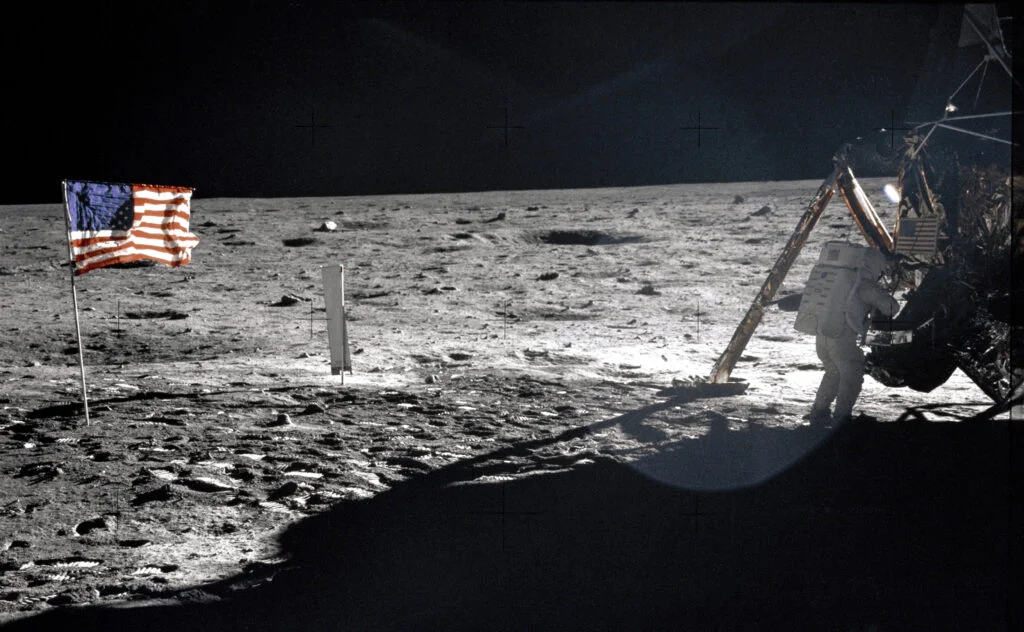

When Neil Armstrong finally descended the ladder and stepped onto the lunar surface, the images themselves were so grainy and indistinct that many viewers initially struggled to make sense of what they were seeing. The lunar module camera transmitted at just 10 frames per second (compared to commercial television’s standard 30 frames), creating jerky movements and a ghostly quality that seemed appropriate for such an otherworldly event. Far from the crystal-clear images we take for granted today, these first lunar pictures required active viewer participation—a kind of collaborative meaning-making as family members pointed to blurry shapes on screen and helped each other interpret the historic images.

The technical limitations paradoxically enhanced the emotional impact for many viewers, as the grainy, low-resolution images emphasized just how far away the astronauts were and the remarkable achievement of receiving any pictures at all from the moon’s surface. The ghostly, almost spectral quality of Armstrong’s first steps seemed to emphasize the borderline supernatural achievement of humans actually walking on another world. Many viewers later recalled that the poor image quality didn’t diminish the experience but rather enhanced it, making the moment feel appropriately dreamlike and surreal.

5. The Network Commentators as Emotional Guides

Television anchors—particularly CBS’s Walter Cronkite—became emotional surrogates for the millions of viewers, providing not just information but modeling appropriate responses to the unfolding events. When the Eagle landed safely on the lunar surface, Cronkite famously removed his glasses, briefly struggled for words, and simply said, “Oh, boy,” momentarily abandoning journalistic distance to express the wonder and relief viewers themselves were feeling. These trusted figures served as emotional guides through unfamiliar territory, helping viewers process the magnitude of what they were witnessing.

The commentary itself was characterized by long periods of respectful silence—a broadcasting approach almost unimaginable in today’s media environment of constant chatter and analysis. These quiet moments allowed the scratchy audio from the lunar surface to take center stage, creating intimate connections between viewers and astronauts despite the quarter-million mile distance separating them. When Armstrong delivered his famous “one small step” line, many commentators remained silent afterward, allowing the historic words to resonate undiminished by immediate analysis or reaction.

6. The Contrast Between Mundane Settings and Extraordinary Events

The juxtaposition between ordinary living rooms and the extraordinary events unfolding on screen created a surreal viewing experience many witnesses still recall vividly. Viewers watched humanity’s greatest adventure while surrounded by the most mundane domestic settings—ashtrays needed emptying, ice in drinks melted, children dozed off on shag carpeting, yet on screen, human beings walked on another world. This collision between the transcendent achievement and ordinary surroundings created a cognitive dissonance that many found profoundly moving.

The limitations of black-and-white television actually emphasized this contrast, as the lunar surface and spacecraft appeared in the same monochromatic tones as the furniture and walls of viewers’ living rooms. One moment, viewers were conscious of sitting on their familiar couch; the next, they were transported mentally to the Sea of Tranquility, toggling between immersion in the historic moment and awareness of their everyday surroundings. This oscillation between the transcendent and the ordinary became a defining characteristic of the viewing experience that color broadcasts or higher-definition images might have actually diminished.

7. The Sounds That Filled the Gaps

While visual information was limited by technology, the audio experience of the moon landing broadcast was surprisingly rich and compelling, creating an auditory landscape that helped viewers fill in the visual gaps. The distinctive crackle of radio transmissions from space, the communication delays, the beeps of telemetry, and the controlled-but-tense voices of mission control created an immersive soundscape that compensated for the visual limitations. Many viewers later recalled closing their eyes during portions of the broadcast, finding the audio alone created a more vivid mental picture than the grainy visuals.

The household sounds surrounding the broadcast became part of the remembered experience as well—the hushing of talkative relatives, the collective gasps at key moments, the occasional bursts of applause in living rooms that mirrored the celebrations at Mission Control. Parents whispered explanations to confused children, amateur space enthusiasts translated technical jargon for their less-informed neighbors, and in many households, someone inevitably cried. These layered soundscapes—broadcast audio and domestic reactions intertwining—created memories that were as much about what was heard as what was seen.

8. The “Is This Really Happening?” Moment

The technological limitations of black-and-white broadcasts, combined with the literally otherworldly nature of the events, created moments of genuine cognitive dissonance where viewers questioned whether what they were seeing was actually real. Unlike today’s sophisticated viewers accustomed to CGI and digital effects, audiences in 1969 had less experience distinguishing between authentic footage and staged productions. The moon landing occurred just months after the release of “2001: A Space Odyssey” with its realistic space visuals, causing some viewers momentary confusion about whether they were watching cinema or reality.

This uncertainty wasn’t about conspiracy theories (those would come later) but rather about the human mind struggling to process something so extraordinary that it temporarily seemed more plausible as fiction than fact. Viewers reported looking away from their televisions to gaze at the actual moon visible through their windows, trying to reconcile the celestial body they’d known all their lives with the knowledge that human beings were now walking on its surface. This cognitive struggle—the mind attempting to update its understanding of what was possible—created a particular kind of wonder that viewers of later space achievements, seen through more sophisticated technology, would never quite experience in the same way.

9. The Imperfect Broadcast as Proof of Authenticity

The technical glitches, transmission dropouts, and poor image quality that would be considered broadcasting failures today actually enhanced the credibility and emotional impact of the moon landing coverage. The very imperfections of the broadcast—moments when the picture dissolved into static, when microphones cut out, when camera movements became disoriented—served as convincing evidence that viewers were watching a genuine remote broadcast from another world rather than something produced in a studio. The flaws in the coverage became part of what made it believable.

Many viewers later recalled that these imperfections created moments of heightened tension and connection, as families collectively held their breath when signals temporarily dropped or images became indecipherable. Unlike modern viewers accustomed to technical perfection, this audience experienced technical limitations as part of the drama—each restored connection after a dropout felt like a small victory, each clarified image after a period of static felt like a gift. The unreliability of the technology paradoxically made the experience feel more immediate and authentic than a more polished production could have achieved.

10. The Commercial Breaks That No One Wanted

Despite the historic nature of the broadcast, network television still included commercial breaks—creating a jarring collision between the transcendent achievement unfolding on the lunar surface and advertisements for household products. Viewers experienced cognitive whiplash moving between Armstrong’s historic words and jingles for laundry detergent or breakfast cereal. These commercial interruptions, considered unthinkable during such broadcasts today, became part of the remembered experience for many viewers—symbols of how the extraordinary was contained within the framework of ordinary broadcasting conventions.

Families developed strategies for managing these unwelcome interruptions, with designated members watching alternate channels to alert everyone when the moon coverage resumed elsewhere. The most memorable commercials became oddly integrated into the moon landing experience itself, with certain jingles or slogans forever associated with the lunar mission in viewers’ memories. Some families avoided commercials altogether by employing multiple television sets tuned to different networks, creating makeshift control rooms where they could switch attention to whichever channel currently showed the lunar surface rather than advertisements.

11. The Physical Strain of Focused Viewing

Watching television in 1969 was physically demanding in ways modern viewers never experience, particularly during extended broadcasts like the moon landing coverage. The small screens (often just 19-21 inches) required viewers to sit much closer than we do today, straining eyes that were focused intently for hours on low-contrast images. The poor resolution meant viewers leaned forward to distinguish details, creating neck and back strain during the marathon viewing sessions that stretched late into the night.

Many viewers reported headaches, eyestrain, and physical exhaustion after watching the broadcast, having maintained uncomfortable positions for optimal viewing angles or having held rabbit ear antennas in specific positions to maintain reception. Unlike modern viewing where content seamlessly follows viewers across devices, this audience was physically tethered to the television set, afraid to move or even blink during crucial moments lest they miss something historic. This physical investment—the actual discomfort endured to witness the moment—became part of what made the viewing experience meaningful and memorable.

12. The Morning-After Processing

For many Americans, particularly on the East Coast where the moonwalk occurred late at night, the full emotional and intellectual processing of what they’d witnessed happened the following day. Monday morning, July 21, became a nationwide collective debriefing, as people arrived at workplaces, summer schools, and neighborhood gathering spots eager to compare experiences and confirm that others had seen and felt what they had. Newspapers with “MAN ON MOON” headlines were purchased not primarily for information—most already knew what had happened—but as tangible mementos of a moment many sensed would define their lifetimes.

The shared viewing experience became social currency, with conversations revolving around where you watched, who you were with, and what you felt during key moments. Television reviewers and cultural commentators struggled to find vocabulary adequate to describe what had just occurred, with many resorting to religious or mythological language to convey the significance. For many viewers, this day-after processing—seeing the event reflected in print media, hearing it discussed on morning radio, and engaging in face-to-face conversations about what they’d witnessed—was when the full emotional impact finally registered, sometimes triggering delayed tears or expressions of wonder that hadn’t surfaced during the broadcast itself.

After watching humanity reach the moon through flickering black-and-white images, viewers in 1969 experienced something subsequent generations never would—the transformation of space travel from science fiction to witnessed reality within the span of a few hours. Those grainy, indistinct television images, technically inferior by modern standards, paradoxically created a more profound viewing experience precisely because of their limitations. The cognitive and imaginative work required to make sense of what they were seeing engaged viewers as active participants rather than passive recipients. As we look back at this watershed moment in human achievement and television history, perhaps the most striking aspect isn’t just that humans walked on the moon, but that millions witnessed it together through technology that barely seemed adequate to the task—yet somehow, in its very inadequacy, created an experience so powerful that it remains vivid in cultural memory more than half a century later.