Throughout history, humans have gone to extraordinary—and often dangerous—lengths in pursuit of beauty ideals that seemed perfectly reasonable at the time. What passed for enhancement in previous eras now appears not just outdated but downright bewildering when viewed through our contemporary lens. While today’s beauty standards certainly aren’t free from criticism, they pale in comparison to some of the bizarre and health-threatening practices our ancestors embraced with enthusiasm. Let’s take a cringe-inducing journey through some of history’s most absurd beauty standards that would rightfully horrify modern sensibilities.

1. Lead-Based Skin Whitening

For centuries across Europe and Asia, the pursuit of pale skin led to the application of white lead-based cosmetics that slowly poisoned users while creating the coveted ghostly complexion. Queen Elizabeth I famously used “Venetian ceruse”—a mixture of white lead and vinegar—to achieve her iconic pale visage, covering her face, neck, and décolletage with this toxic paste. The poisonous makeup not only caused skin deterioration, hair loss, and rotting teeth but also led to more severe symptoms like paralysis and eventual death from lead poisoning, with users often applying more product to cover the damage caused by previous applications. The Conversation frames the usage of this substance as essentially losing a life in the name of makeup.

This beauty standard was rooted in classism—pale skin signified wealth and nobility (indicating one didn’t work outdoors in the sun), creating a feedback loop where women destroyed their health pursuing an appearance that ironically made them look increasingly ill. The tragic irony lies in how the pursuit of this beauty standard literally killed its most dedicated followers, with some noblewomen experiencing tremors, cognitive decline, and painful deaths while society praised their increasingly corpse-like appearance as the height of sophistication. Despite clear evidence of its dangers, lead-based cosmetics remained popular for over 300 years, showing how powerful social beauty standards can override even the most basic survival instincts.

2. Foot Binding in China

For approximately 1,000 years, young Chinese girls endured excruciating foot binding—a process that broke the arch and toes to create the coveted “lotus foot” measuring just 3-4 inches long. Beginning between ages 4-9, girls’ feet were soaked in hot water, toenails cut short, toes folded under the sole, and the entire foot wrapped tightly with long bandages that restricted growth and broke bones over time. The bindings would be periodically removed for cleaning, only to be wrapped again even tighter, with the process causing rotting flesh, infections, and lifelong disability as the ideal outcome. Smithsonian Magazine explores not just the history of its practice but why it stuck around for so long.

What makes this practice particularly disturbing is how completely it transformed normal human function—women with bound feet could barely walk without assistance, essentially ensuring they remained homebound and dependent. The tiny, pointed feet created what society considered an alluring swaying walk (called the “lotus gait”) but in reality was the painful hobbling of a permanently disabled person. The practice persisted despite multiple attempted government bans because having a daughter with bound feet significantly increased her marriageability, creating impossible choices for families caught between their daughters’ physical welfare and their social and economic futures.

3. Arsenic Complexion Wafers

In the Victorian era, women consumed arsenic wafers and arsenic-laced potions to achieve translucent skin, rosy cheeks, and sparkling eyes—all temporary effects of low-grade arsenic poisoning. Companies marketed these products with names like “Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers” or “Arsenic Eating Complexion Wafers,” promising users they would clear blemishes and create the pale, delicate look so prized in Victorian beauty standards. Regular users developed a dependency on the toxin, experiencing withdrawal symptoms if they attempted to stop, while those who continued faced the consequences of chronic arsenic poisoning. Curology also puts into perspective just how dangerous and deadly these treatments could be.

The most chilling aspect of this beauty treatment was how it was marketed as a health product, with advertisements claiming benefits for various ailments alongside beauty enhancement. Testimonials praised the “plumpness of form” and “roundness of limbs” that resulted—both actually symptoms of arsenic-induced fluid retention rather than healthy weight gain. The practice gradually faded as understanding of toxicology improved, but not before countless women damaged their nervous systems, livers, and kidneys in pursuit of a beauty standard that essentially glorified the early symptoms of poison-induced illness.

4. Mercury Treatments for Freckles and Blemishes

Before modern dermatology, mercury compounds were slathered on faces to eliminate freckles, age spots, and acne—often successfully removing the offending marks by destroying surrounding skin tissue. Women in Renaissance Europe, 18th and 19th century America, and even early 20th century consumers applied mercury-laden creams and lotions without understanding they were exposing themselves to a powerful neurotoxin that could cause tremors, memory problems, kidney damage, and potentially madness. The treatment quite literally peeled away layers of skin, temporarily creating the desired uniformity of complexion before more serious symptoms developed.

The deeply troubling aspect of mercury treatments was their prevalence in products specifically marketed to women of color, with skin-lightening mercury creams remaining available in some countries well into the 20th century. Users often experienced a devastating cycle—initial positive results followed by new skin problems caused by the mercury itself, leading to increased use of the very product causing the damage. The compulsion to eliminate what are now recognized as completely normal skin features led countless women to trade their cognitive function and ultimately their lives for temporary conformity to an arbitrary beauty standard that rejected natural human variation.

5. Belladonna Eye Drops

Renaissance women and Victorian ladies alike dripped juice from the deadly nightshade plant (belladonna) directly into their eyes to dilate their pupils to achieve a wide-eyed, doe-like appearance considered the height of feminine allure. The practice temporarily created what poetry of the time called “luminous” and “lustrous” eyes—with belladonna literally translating to “beautiful woman” in Italian. The immediate effects included blurred vision, inability to focus, and increased sensitivity to light, while repeated use could lead to permanent blindness.

What’s particularly disturbing about this beauty standard is how it essentially glorified the physical symptoms of fear, arousal, or fever—dilated pupils being a physiological response to these conditions. The practice continued for centuries despite well-documented knowledge of belladonna’s toxicity, with women literally trading their eyesight for the temporary appearance of enlarged pupils. Commercial preparations were sold under names like “Lash Lure” well into the early 20th century, causing numerous cases of blindness before regulation finally restricted these products.

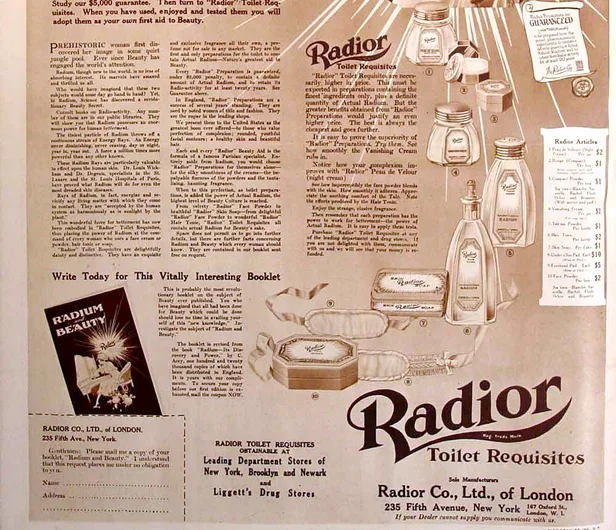

6. Radium Beauty Products

Following the discovery of radium in 1898, the radioactive element became a sensation in beauty products of the early 20th century, with items like Tho-Radia cream (containing thorium and radium) promising to rejuvenate skin, eliminate wrinkles, and restore youthful vitality. Radium-infused face creams, powders, and even drinking water marketed the element’s “energizing rays” as the scientific breakthrough women had been waiting for. The products created a temporary illusion of vitality through radiation exposure that stimulated skin, while quietly causing cellular damage that would manifest years later as cancer.

The tragic ignorance surrounding radiation’s dangers allowed these products to be marketed as cutting-edge scientific advancements rather than the deadly poisons they actually were. Advertising emphasized the mysterious “glow” and “energy” that radium products imparted—ironically accurate descriptions of radiation effects but misinterpreted as positive benefits. Companies prominently featured scientific terminology and images of laboratories to lend credibility to products that were essentially delivering slow-acting poison to consumers desperate to meet beauty standards through what they believed was modern science.

7. Tapeworm Diet Pills

In the early 1900s, diet pills allegedly containing tapeworm eggs offered women an effortless way to lose weight—allowing them to eat whatever they wanted while the parasite consumed the excess calories. Advertisements promised dramatic weight loss without exercise or eating restrictions, a tempting prospect for women pursuing the increasingly slender ideal female body of the early 20th century. While many of these pills were likely fraudulent and didn’t actually contain viable tapeworms, some unfortunately did, leading to dangerous intestinal infections.

The disturbing reality of this beauty standard was the glorification of internal parasitic infection as preferable to natural body size variation. Women who did ingest viable eggs experienced not just weight loss but anemia, malnutrition, intestinal blockages, and potentially death if the tapeworm migrated beyond the digestive tract. The practice highlights the extraordinary risks women throughout history have been willing to take to achieve body standards, with the true horror being that some modern extreme dieting practices are barely less dangerous than deliberately introducing parasites into one’s body.

8. Tuberculosis Chic

In the 19th century, the wasting appearance of tuberculosis—pale skin, hollow cheeks, bright eyes, and extreme slenderness—became so fashionable that healthy women emulated the look of a deadly disease. The “consumptive aesthetic” was associated with heightened spiritual and artistic sensitivity, leading women to use white powder to appear paler, rouge concentrated on the cheekbones to mimic feverish flush, and belladonna to create the characteristic bright-eyed appearance of someone with a dangerously high temperature. Some went as far as deliberately losing weight and avoiding sunlight to better mimic the disease’s effects.

What makes this beauty standard particularly perverse is that it idealized the appearance of people suffering from a painful, debilitating condition that was the leading cause of death for young women during this period. The romanticization of tuberculosis in literature, art, and fashion created a beauty standard literally modeled on dying women, with consumption considered a “beautiful death” despite the reality of sufferers coughing up blood and slowly suffocating. This morbid ideal reflected cultural attitudes that equated female fragility with refinement and spiritual purity, essentially celebrating the physical manifestation of suffering as aesthetically desirable.

9. Corsets and Waist Training

For several centuries, women endured the constriction of whalebone, steel, or reed corsets that compressed the torso to create exaggerated hourglass figures—sometimes reducing waist circumference by 10 inches or more. Victorian tight-lacing reached extreme levels, with fashionable waist measurements of 16-18 inches requiring years of gradually increased constriction. The practice compressed internal organs, restricted breathing, deformed the ribcage, and caused digestive problems, while limiting women’s physical activities and sometimes causing fainting from inability to breathe properly.

Perhaps most shocking to modern sensibilities is how this practice literally reshaped women’s bodies permanently—early tight-lacing of young girls could deform developing ribcages, leading to lifelong physical alterations. X-rays from the period show displaced floating ribs, compressed lungs, and shifted internal organs in dedicated corset wearers. The practice created a physical dependence, with muscles atrophying to the point where women couldn’t support themselves without their corsets after years of wear. Despite clear medical evidence of harm, the practice persisted because a tiny waist was considered the definitive mark of feminine beauty, social status, and moral virtue.

10. Cosmetic Lead and Mercury Eyebrows

Ancient Romans and Greeks plucked their natural eyebrows entirely, replacing them with artificial brows made from goat’s hair attached with sticky resin or painted-on substitutes containing lead. In Renaissance Europe and 18th century England, fashionable eyebrows were replaced with false brows made from mouse skin or completely removed and replaced with drawn-on lines using lead and mercury compounds. The toxic metals caused skin irritation, infections, and systemic poisoning, while the complete removal of natural brows sometimes resulted in permanent hair loss.

The extremity of this beauty standard is particularly evident in how it rejected a natural facial feature entirely, replacing it with an artificial version that exposed users to serious health risks. The complete denaturalization of the face—replacing a perfectly functional feature with toxic substitutes—demonstrates how beauty standards can push people to reject even the most basic aspects of their natural appearance. The psychological impact of such comprehensive self-alteration likely created a profound disconnection from one’s natural appearance that resonates with modern concerns about beauty dysmorphia.

11. Strychnine as a Complexion Treatment

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, small doses of strychnine—a powerful poison used primarily as rat killer—were consumed as a beauty tonic to improve complexion and energy levels. Women took “arsenic and strychnine pills” to brighten their complexions, stimulate flushed cheeks, and create brighter eyes, all effects of mild poisoning. Strychnine’s stimulant properties provided temporary energy boosts that were misinterpreted as improved health rather than the body’s stress response to toxicity.

The most disturbing aspect of this practice was how it encouraged women to develop tolerance to a deadly poison, walking a precarious line between beauty enhancement and fatal overdose. Regular users developed physical dependencies, requiring increasing doses to achieve the same effects—a dangerous proposition with a substance where the therapeutic dose and lethal dose are separated by a narrow margin. The glorification of symptoms like flushed skin and bright eyes—actually stress responses to poison—reveals how beauty standards can distort perception to the point where signs of physical distress are reinterpreted as desirable aesthetic qualities.

12. Intentional Consumption of Arsenic for Pale Skin

Beyond arsenic wafers, some 19th-century women in Alpine regions practiced deliberate, sustained arsenic consumption, gradually building tolerance to achieve the pale complexion and plumpness associated with arsenic exposure. “Arsenic eaters” consumed the poison in gradually increasing amounts, beginning with rice-grain sized portions and increasing over time. The practice was particularly common among young women seeking to increase their marriageability through the coveted “snow-white” complexion that arsenic temporarily produced.

What makes this practice especially disturbing was the community knowledge and acceptance of its deadly nature—practitioners understood they were consuming poison and that stopping would cause withdrawal symptoms including digestive distress, nervous disorders, and a greenish complexion. The practice created lifelong dependency, as discontinuing arsenic consumption after developing tolerance led to more severe symptoms than never having consumed it at all. This beauty standard essentially trapped women in perpetual self-poisoning, creating a lifetime commitment to consuming a toxin with no safe exit strategy.

These historical beauty standards serve as stark reminders of how cultural pressures can override even the most basic instincts for self-preservation. While today’s beauty ideals certainly warrant critical examination, they generally don’t involve deliberately consuming poison or permanently disabling oneself. The extremes our ancestors went to in pursuit of beauty highlight the powerful social forces that shape our ideals of attractiveness and the lengths humans will go to conform to them. Perhaps the most valuable lesson from these historical practices is to question which current beauty standards future generations might look back on with similar horror and disbelief.