Tony Curtis began his career as Hollywood’s idea of the perfect heartthrob—those blue eyes, that wavy hair, the chiseled features that adorned many a movie poster in the 1950s. But beneath that matinee idol exterior lurked a surprisingly versatile comedian with impeccable timing and a willingness to shed his vanity for a laugh. While initially typecast for his looks, Curtis fought hard to show audiences and studios alike that he possessed far more than just a pretty face. These thirteen moments from his career showcase how he used humor to transcend his heartthrob image and establish himself as one of Hollywood’s most underrated comic talents.

1. The Teaching Sequence in “The Bad News Bears Go to Japan” (1978)

In the third installment of the Bad News Bears franchise, Curtis plays a scheming promoter who brings the youth baseball team to Japan. The scene where he attempts to teach the American children about Japanese customs creates comedy through cultural misunderstandings and his increasing frustration. His character’s combination of limited knowledge and absolute confidence created perfect comic tension as he dispensed entirely incorrect information with complete authority. IMDb doesn’t have the highest ratings for this film, which goes to show how much Curtis carried it as far as he could.

What made this sequence work was Curtis’s portrayal of a man barely one step ahead of his audience, attempting to bluff his way through a situation beyond his expertise. His performance captured the specific comedy of an overconfident American blundering through cultural differences while maintaining absolute certainty in his approach. Curtis’s willingness to play an unscrupulous character while still making him oddly likable showcased his ability to find the humanity in flawed characters, making the comedy richer and more dimensional.

2. The Bathtub Scene in “Spartacus” (1960)

Though “Spartacus” is remembered as an epic historical drama, Tony Curtis delivered one of the film’s most memorable moments in the bathtub scene with Laurence Olivier’s Crassus. As the slave Antoninus, Curtis masterfully plays coy innocence while discussing Romans’ culinary preferences for “snails or oysters” – a thinly veiled conversation about orientation that somehow slipped past 1960s censors. His deadpan delivery during the scene created tension, humor, and subtext that modern audiences still analyze. VFX Voice also credits this film as a whole with revolutionizing cinema for all time.

The genius of Curtis’s performance comes from his ability to maintain absolute composure while delivering loaded double entendres with perfect innocence. The scene showcases his ability to create comedy through subtle reactions rather than broad physical gags. When his character later flees , the preceding bathtub conversation gains additional layers of humor that established Curtis could hold his own in sophisticated comedy even opposite the intimidating presence of Olivier.

3. The Landlord Impression in “The Great Race” (1965)

In Blake Edwards’ slapstick comedy “The Great Race,” Curtis mostly played the straight man as the impossibly perfect hero “The Great Leslie,” but he broke character for a hilarious impression of a lecherous landlord while trying to gain entry to Natalie Wood’s room. Affecting a ridiculous accent and hunched posture, his sudden transformation from dashing hero to comedic character actor demonstrated remarkable versatility within a single scene. The quick switch back to his heroic persona made the moment even funnier. Movies Silently puts into perspective how much this film came at a revolutionary point in film history.

What makes this brief scene so noteworthy is how Curtis willingly stepped out of his handsome leading man role to deliver a moment of pure character comedy. Though the film gave most of the broad comedy to Jack Lemmon’s villainous Professor Fate, Curtis proved he could steal a scene with perfect timing and character work when the opportunity arose. His commitment to the ridiculous impression while maintaining Leslie’s underlying propriety created a perfectly balanced comic moment that showcased his range.

4. Pretending to Be Deaf in “Operation Petticoat” (1959)

In this Blake Edwards comedy about a pink submarine, Curtis plays Lt. Nicholas Holden, a conniving officer who pretends to be deaf to avoid answering difficult questions from his superior officer (Cary Grant). The scene builds beautifully as Curtis deliberately mishears questions, responds with non-sequiturs, and maintains an expression of innocent confusion while driving Grant’s character to increasing frustration. His perfectly timed “What?” after each question created a rhythm of comedy that demonstrated his gift for repetition without becoming tedious.

What elevated this scene was Curtis’s ability to play multiple layers simultaneously—the character pretending to be deaf, while the audience knows he’s faking, while also reacting legitimately to Grant’s growing frustration. His exit from the scene, where he immediately drops the pretense once safely away from Grant’s character, delivered the perfect punctuation mark to the charade. This performance opposite his childhood idol Cary Grant showed Curtis had developed his own distinctive comic timing while learning from Hollywood’s best.

5. The Prison Impersonation in “The Great Impostor” (1961)

Based on the true story of Ferdinand Waldo Demara, “The Great Impostor” gave Curtis the chance to play multiple roles within one character as a man who successfully impersonated everything from a prison warden to a surgeon. The sequence where he impersonates a prison guard contains a particularly hilarious moment when, after being appointed warden, he must inspect the prison kitchen—the very place where he previously worked as an inmate. His barely contained panic and improvised expertise created a masterclass in comedic anxiety.

The brilliance of this performance came from Curtis’s ability to layer the character’s mounting stress beneath a facade of authority. Every gesture—from nervously straightening his uniform to overcompensating with excessive officiousness—built the comedy organically. His scenes with the actual former prison cook who might recognize him showcase physical comedy through subtle reactions rather than broad slapstick, with Curtis’s expressive eyes doing much of the comedic heavy lifting as his character desperately hopes to avoid exposure.

6. Playing the Bumbling Detective in “40 Pounds of Trouble” (1962)

In this underappreciated comedy, Curtis plays casino manager Steve McCluskey who gets saddled with a young orphan girl while also being pursued by process servers trying to deliver alimony papers. The scene where he attempts to evade detection at Disneyland (the first film given permission to shoot there) showcases his talent for physical comedy and mounting frustration. His increasingly desperate attempts to disguise himself while maintaining his cool in front of the child created a perfect comic juxtaposition.

What made this performance stand out was Curtis’s willingness to play incompetence—a stark contrast from his typical smooth-operator roles. His character’s elaborate plans consistently backfire in increasingly humiliating ways, requiring Curtis to react with physical comedy that built in intensity throughout the film. The Disneyland chase scene in particular showed his gift for location-specific comedy, using the park’s features for gags that revealed both physical agility and impeccable timing as he dodged behind attractions and inadvertently joined parades.

7. His Self-Parody in “The Mirror Crack’d” (1980)

In this Agatha Christie adaptation, Curtis essentially parodied himself and his Hollywood contemporary image by playing film star Martin Fenn. The character’s vanity, insecurity about aging, and desperate attempts to maintain his youthful image gave Curtis the opportunity to poke fun at his own heartthrob history. His scene discussing the challenges of aging in Hollywood with his on-screen wife (a similarly self-parodying Elizabeth Taylor) contained layers of meta-commentary that revealed Curtis’s healthy sense of humor about his own career.

The genius of this performance was Curtis’s willingness to mine his own public persona for comedy, acknowledging the very image issues that had both helped and hindered his career. His character’s excessive concern with camera angles, lighting, and appearance allowed Curtis to exaggerate the very real pressures faced by actors known for their looks. By embracing these insecurities and playing them for laughs, he demonstrated both self-awareness and the confidence of an actor who had transcended being just a pretty face to become a genuine talent comfortable enough to laugh at himself.

8. The Helicopter Lesson in “Boeing, Boeing” (1965)

In this adaptation of the French farce, Curtis plays reporter Robert Reed, who becomes entangled in his friend’s complicated scheme to juggle relationships with three flight attendants. The scene where Curtis attempts to explain the friend’s methodical dating system while using toy helicopters as visual aids showcases his gift for escalating absurdity and physical comedy. As the explanation becomes increasingly convoluted, Curtis’s growing enthusiasm for the ridiculous plan reveals his perfect understanding of how commitment enhances comedy.

What makes this moment particularly funny is Curtis’s absolute conviction as his character admires the mathematical precision of a system the audience recognizes as patently ridiculous. Using the toy helicopters with increasing animation while explaining the careful timing required to keep the flight attendants from discovering each other, his performance builds from subtle amusement to manic energy. The scene demonstrates his ability to find humor in exposition—turning what could have been dull explanation into one of the film’s comedic highlights.

9. The Disguise Sequence in “Not with My Wife, You Don’t!” (1966)

In this comedy about marital jealousy, Curtis plays Tom Ferris, who suspects his wife’s old flame is trying to rekindle their romance. The scene where he disguises himself as an Italian count to spy on them demonstrates Curtis’s willingness to go all-in on an outlandish characterization. With an exaggerated accent, flamboyant gestures, and absurd facial hair, he created a character within a character that showcased his commitment to physical transformation for comedic effect.

The brilliance of this performance comes from Curtis playing multiple psychological layers simultaneously—his character’s terrible acting, jealous surveillance, and mounting frustration when his wife doesn’t recognize him despite the obvious disguise. His increasingly desperate attempts to maintain the facade while gathering information build to a perfectly timed comic payoff. The sequence demonstrated Curtis’s understanding that comedy often works best when characters take ridiculous situations with absolute seriousness.

10. The Auction Bidding War in “The Boston Strangler” (1968)

Though primarily a dramatic film where Curtis delivered one of his most acclaimed serious performances as Albert DeSalvo, “The Boston Strangler” contains an unexpected moment of humor during a society fundraiser. As various wealthy Bostonians bid on items, Curtis’s character—presented as a workman doing repairs—begins bidding substantial amounts, creating confusion and consternation among the upper-class crowd. His deadpan delivery and subtle enjoyment of their discomfort created a moment of perfect dark comedy within the otherwise tense film.

What makes this brief scene remarkable is how Curtis uses it to reveal a dimension of his character while also providing a moment of comic relief in a dark story. His understated approach—maintaining an expression of innocent confusion while deliberately disrupting social norms—demonstrated how precisely he could calibrate a performance to serve both narrative and comedic purposes. The moment showed Curtis’s ability to find humor in unexpected places without undermining the film’s serious themes.

11. The Gangster Dance in “Lepke” (1975)

In this biographical film about notorious gangster Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, Curtis mostly played the role straight, but injected dark humor into unexpected moments. In one memorable scene, after eliminating a rival, his character performs an impromptu celebratory dance that’s both chilling and absurdly funny. The incongruity of this brutal criminal performing a brief, almost childlike jig created a moment of uncomfortable humor that revealed volumes about the character’s psychology.

The effectiveness of this brief comic moment came from its unexpected nature and Curtis’s absolute commitment to the character’s warped perception. Rather than playing for laughs, he showed how the character’s distorted worldview made violence a cause for celebration. This dark humor demonstrated Curtis’s understanding that comedy doesn’t always need to be likable—sometimes it’s most effective when revealing uncomfortable truths about human nature. His willingness to find these complex notes in a biographical drama showed his continuing evolution as an actor beyond traditional comedy.

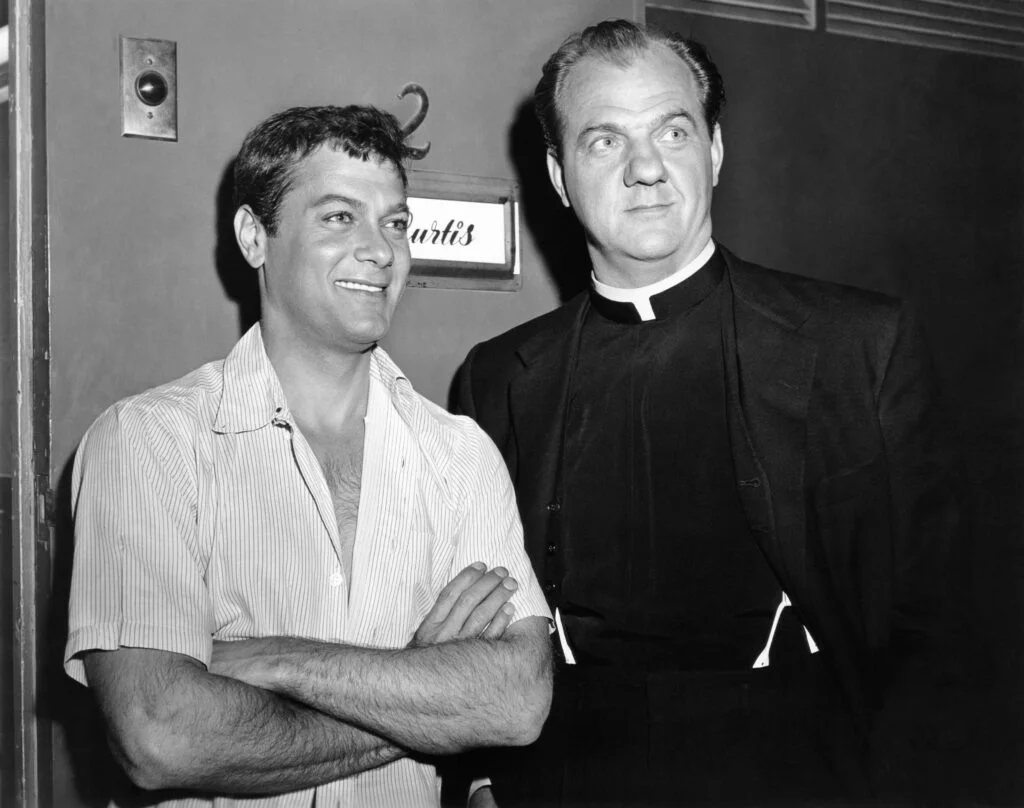

12. Dressing in Drag in “Some Like It Hot” (1959)

Tony Curtis’s transformation into “Josephine” in Billy Wilder’s masterpiece comedy required him to abandon all vanity and embrace full-on physical comedy. His distinctive Bronx accent poking through his feminine disguise created a hilarious contrast that added layers to the performance. The scene where he struggles to maintain his composure while sharing a train berth with Marilyn Monroe showcased both his comedic chops and his willingness to play against his matinee idol image.

What made this performance particularly remarkable was Curtis’s commitment to the absurdity without winking at the audience. When his character further disguises himself as a millionaire to woo Sugar Kane (Monroe), his deliberately ridiculous Cary Grant impression revealed a talent for vocal comedy that surprised audiences who knew him primarily from dramatic roles. His willingness to appear ridiculous—stuffing his chest with hot water bottles and wobbling precariously in heels—helped create one of cinema’s most beloved comedies while proving Curtis was an actor first and a pretty face second.

Tony Curtis’s journey from matinee idol to respected comic actor represented a triumph of talent over typecasting. Through these thirteen performances and many others, he proved that true star power comes not from perfect features but from the willingness to use those features in service of character, story, and—when appropriate—absolute hilarity. His comedic legacy deserves greater recognition among cinema’s great funny men, not least because he had to overcome the considerable obstacle of his own handsomeness to prove just how funny he could be. For an actor initially hired for his looks, Curtis had the last laugh by showing that his greatest asset was never his face—it was what he could do with it.