Long before content warnings and helicopter parenting, children of the ’70s and ’80s regularly found themselves white-knuckling through supposedly family-friendly films that left lasting psychological impressions. What makes these cinematic experiences so memorable isn’t just that they were scary—it’s that they ambushed us with their terror, hiding behind colorful posters and G or PG ratings that gave parents no reason for concern. Here’s our countdown of twelve films marketed to children that contained nightmare fuel we never saw coming.

1. The Secret of NIMH (1982)

Don Bluth’s beautifully animated tale about a widowed mouse trying to save her home seems innocent enough—until you realize it’s packed with graphic violence, medical experimentation, and existential dread. The scene where Mrs. Brisby visits the Great Owl features some of the most atmospheric horror ever created in children’s animation, with decaying animal skeletons littering his lair and massive, unblinking eyes emerging from the darkness. The film’s scientific backstory involving cruel laboratory testing on animals introduced many children to concepts of mortality and suffering that Disney would never have touched. Even today, AV Club writes that this movie has the power of leaving every young viewer with lingering anxiety.

What made NIMH particularly unsettling was its refusal to soften its darker elements with comic relief or reassuring winks to the audience. The blood-red backlit animation during the film’s numerous death scenes, the uncomfortably realistic depiction of mud slowly suffocating characters, and the nightmarish visions filled with rotting corpses conveyed a respect for children’s ability to process genuine fear. Parents who picked this film based on its cute mouse protagonist had no idea they were subjecting their kids to sophisticated psychological horror that rivaled adult thrillers of the era.

2. Watership Down (1978)

This animated adaptation of Richard Adams’ novel about rabbits seeking a new home delivers some of the most traumatizing imagery ever marketed to children. The film’s unflinching depiction of bloody rabbit warfare, complete with torn throats and bulging eyes, has seared itself into the memory of unsuspecting youngsters for generations. The sequence where the fields “run red with blood” wasn’t metaphorical—the screen literally floods with crimson as rabbits tear each other apart in a primal battle for survival. The Independent credits this particular film with traumatizing a whole entire generation.

Perhaps most disturbing was the character of General Woundwort, whose menacing presence and brutal violence created a villain more genuinely frightening than most adult horror antagonists. The film’s apocalyptic visions, featuring a grotesque black rabbit of death and fields filling with blood, introduced countless children to graphic violence with no warning whatsoever. Parents who assumed that animated rabbits meant gentle entertainment found themselves comforting traumatized children who had just witnessed what amounted to “Apocalypse Now” with long ears.

3. The Dark Crystal (1982)

Jim Henson and Frank Oz created a fantasy world unlike anything children had seen before—one filled with grotesque creatures, existential dread, and body horror that would make David Cronenberg proud. The villainous Skeksis, with their decaying bodies, cruel experiments, and death rituals, were nightmare fuel disguised as puppetry. The infamous “essence draining” scene, where a helpless creature is strapped to a chair and has its life force painfully extracted until it withers into a mindless husk, traumatized an entire generation of children who expected Muppet-style hijinks. Cinemablend recounts how subsequent titles worked hard to maintain the movie’s legacy, especially the task of terrifying viewers.

What made The Dark Crystal particularly unsettling was its alien atmosphere—a world without a single human character to provide comfort or familiarity. The film’s sound design, featuring labored breathing, creaking joints, and inhuman screams, created an immersive sense of wrongness that followed children into their dreams. Parents who trusted the Henson name from Sesame Street found themselves with wide-eyed children unable to sleep, haunted by images of vulture-like creatures feasting on putrid food and draining the life essence from innocent beings.

4. Return to Oz (1985)

Disney’s unofficial sequel to the beloved classic took a sharp turn into psychological horror territory, trading Judy Garland’s technicolor wonderland for a dystopian nightmare. The film opens with Dorothy receiving electroshock therapy to “cure” her of her Oz delusions—a disturbing premise that immediately signals this isn’t your mother’s Oz. The Wheelers—humans with wheels instead of hands and feet who screech maniacally as they pursue Dorothy—remain one of cinema’s most unsettling creations, delivering terror through their unnatural movements and inhuman shrieks.

Perhaps most traumatizing was Princess Mombi, who collected heads like handbags, swapping them out depending on her mood while keeping her victims alive and conscious in glass cabinets. The scene where her headless body gropes around for Dorothy in the darkness has caused more childhood trauma than most acknowledged horror films. Parents who thought they were treating their kids to more yellow brick road adventures instead subjected them to a surrealist nightmare featuring mental institutions, decapitation, and living garden ornaments frozen in eternal screams.

5. The NeverEnding Story (1984)

Behind the fantasy adventure lurked existential concepts far beyond what most children could process, creating a psychological horror disguised as a magical quest. The death of Artax the horse in the Swamp of Sadness—where the beloved animal slowly sinks into mud while his young owner screams in anguish—was traumatic enough by itself. But the film went further with the Nothing—a conceptual antagonist representing the death of imagination and hope—introducing children to the concept of nihilistic void and cultural entropy.

The G’mork, a wolf-like creature who explains that the Nothing will leave humans “without hopes and without dreams,” delivered philosophical horror more disturbing than any jump scare. The film’s climactic scene where Fantasia crumbles into fragments of light around a child who has lost everything introduced many young viewers to concepts of loss and cosmic insignificance rarely explored in children’s entertainment. Parents who approved this film based on its fantasy elements had no warning about its profound psychological darkness or its willingness to destroy beloved characters in front of traumatized young audiences.

6. The Watcher in the Woods (1980)

Disney ventured into supernatural horror with this tale of an American family moving into a British mansion haunted by the disappearance of a young girl decades earlier. The frequent visions of a blindfolded girl screaming for help while trapped in another dimension terrified young viewers who expected typical Disney fare. The film’s use of mirrors, strange lights, and whispered voices created an atmosphere of dread more effective than many R-rated horror films of the era.

What made this film particularly disturbing was its grounding in reality—unlike fantasy films where the terror could be dismissed as impossible, The Watcher used real-world settings and plausible scenarios as its foundation. The séance scene, where a young girl becomes possessed and speaks in another voice while objects fly around the room, introduced many children to concepts of the occult with Disney’s apparent approval. Parents who trusted the Disney brand were blindsided by a genuine supernatural thriller that borrowed techniques from The Exorcist and The Haunting while marketing itself to children.

7. The Last Unicorn (1982)

This animated fantasy hid existential horror behind its magical unicorn protagonist and colorful animation style. The Red Bull—a monstrous creature made of flame that hunts unicorns to the ends of the earth—pursued the last unicorn with a relentless, primal menace that haunted children’s dreams. The harpy scene, featuring a three-breasted bird-woman with decaying human features who brutally kills a witch on screen, delivered body horror in a film supposedly meant for young viewers.

The film’s themes of mortality, loss of innocence, and the death of magic created a profound melancholy rarely seen in children’s entertainment. The unicorn’s transformation into a human woman—presented as a form of death rather than a magical gift—introduced children to concepts of lost identity and the pain of consciousness. Parents who selected this film based on its unicorn protagonist had no warning about its meditations on mortality, scenes of violence, or its ultimately heartbreaking message about the impossibility of regaining innocence once it’s lost.

8. Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983)

Another Disney foray into horror, this adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s novel about a sinister carnival arriving in a small town delivered sophisticated terror disguised as family entertainment. Mr. Dark, played with menacing charm by Jonathan Pryce, offered townsfolk their deepest desires—with horrifying consequences that explored the dark side of human nature. The scene where a beautiful woman ages into a withered corpse introduced many children to body horror and the existential fear of aging and death.

The film’s exploration of temptation and human weakness created villains far more disturbing than typical antagonists in children’s films—ones that exposed the darkness within ordinary people rather than external monsters. The tarantula scene, where the creatures crawl over a paralyzed boy unable to scream, exploited primal fears in ways typically reserved for adult horror. Parents who trusted Disney’s family-friendly reputation were unprepared for a film that explored the corrupting power of desire and featured scenes of children being hunted by supernatural forces that understood their deepest fears.

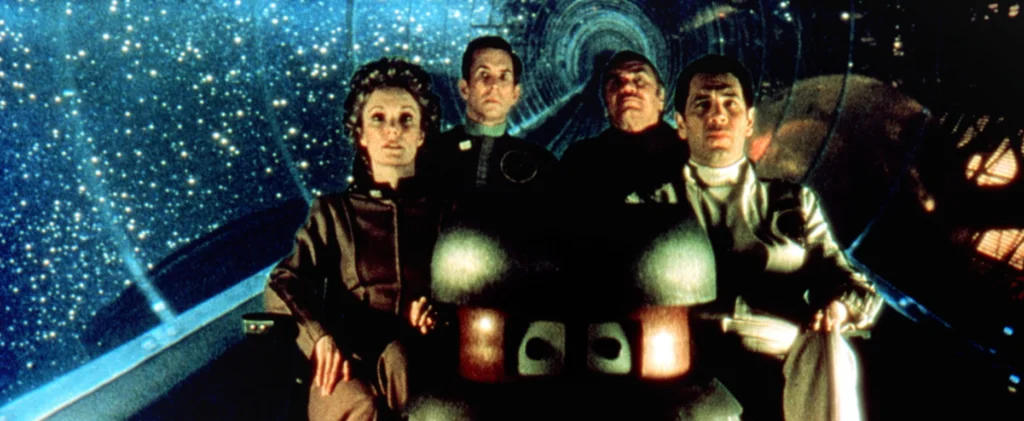

9. The Black Hole (1979)

Disney’s science fiction effort began as a Star Wars competitor but veered into cosmic horror territory with its finale. The film’s villain, Dr. Hans Reinhardt, becomes increasingly unhinged throughout the story, eventually revealing he has lobotomized his former crew and turned them into soulless robot servants. The red-eyed robot Maximilian remains one of Disney’s most frightening creations, especially during the scene where he murders a crew member with his whirling blades.

The film’s journey through the titular black hole becomes a surreal descent into what appears to be literal Heaven and Hell, complete with angelic figures and a demonic landscape of fire. The final image—the evil Dr. Reinhardt merging with Maximilian in what appears to be the afterlife—introduced children to concepts of eternal damnation wrapped in Disney packaging. Parents expecting space adventures similar to Star Wars instead found existential questions about death, the afterlife, and the nature of humanity that left children staring wide-eyed at the ceiling long after bedtime.

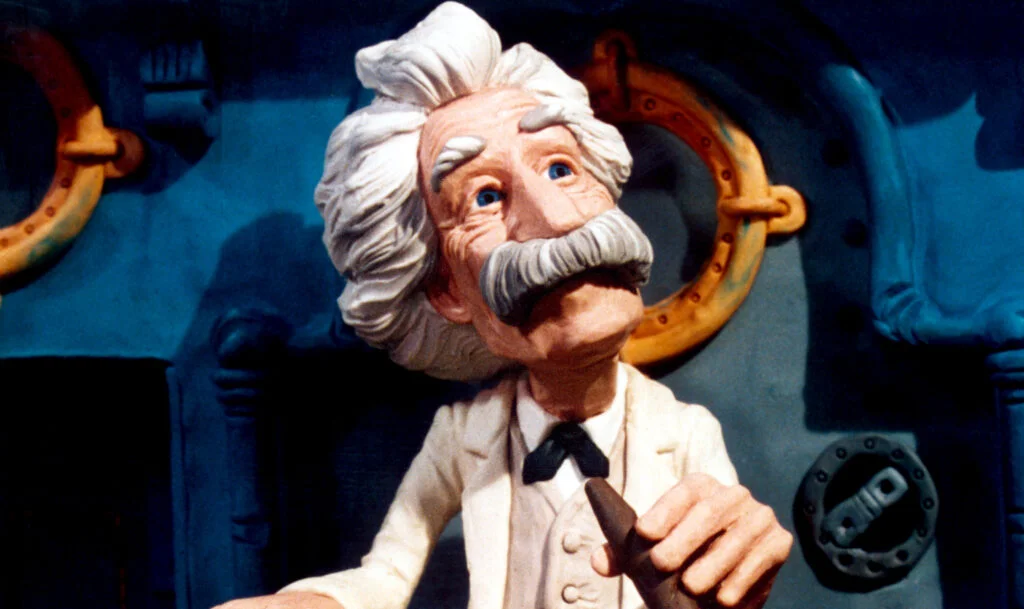

10. The Adventures of Mark Twain (1985)

This stop-motion film featured beloved American characters Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, and Becky Thatcher—then subjected them to cosmic horror beyond human comprehension. The infamous “Mysterious Stranger” sequence features the children meeting Satan himself, who creates tiny clay people only to destroy them while delivering a nihilistic monologue about the meaninglessness of human existence. Children watched as Satan casually destroyed his creations while explaining that “life itself is only a vision, a dream,” introducing concepts of existential meaninglessness in what was marketed as an educational adventure.

The film’s framing story—Mark Twain piloting an airship toward Halley’s Comet to end his life—grounded its fantastic elements in a suicide narrative rarely addressed in children’s entertainment. The dark philosophical musings, surreal imagery, and cosmic despair created an atmosphere more aligned with Lovecraftian horror than children’s entertainment. Parents who selected this film for its educational value and classic literary characters had no warning about its unflinching exploration of mortality, nihilism, and the casual cruelty of existence.

11. Labyrinth (1986)

Jim Henson’s fantasy starring David Bowie as the Goblin King contained psychological horror elements that weren’t apparent from its marketing. The film’s premise—a baby brother stolen by goblins after his sister’s careless wish—tapped into primal childhood fears of responsibility and loss. The helping hands scene, where Sarah falls into a pit only to be caught by dozens of disembodied hands that form faces and speak to her, created body horror that seemed designed specifically to invade children’s nightmares.

The Junk Lady sequence, where Sarah is nearly buried under the weight of her own materialistic desires, delivered psychological horror more sophisticated than most adult thrillers. Jareth’s manipulation of Sarah throughout the film, including a drugged dream sequence with disturbing masked figures, introduced children to concepts of gaslighting and psychological control. Parents who expected a straightforward fantasy adventure found themselves explaining dream manipulation, existential choices, and the film’s uncomfortable subtext of adolescent awakening to confused children who just wanted to see puppets and magic.

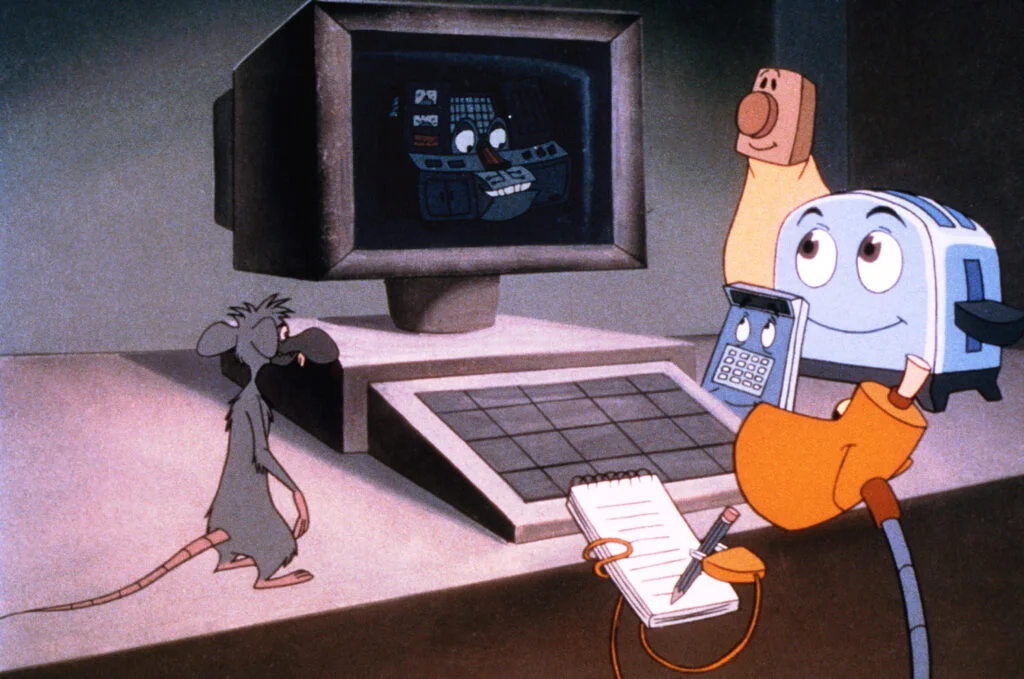

12. The Brave Little Toaster (1987)

This animated film about household appliances searching for their master hid profound darkness behind its cheerful premise. The junkyard scene, where old cars sing about their meaninglessness before being crushed to death on screen—complete with visible terror and screams cut short—introduced children to industrial horror and existential dread. The nightmare sequence featuring a demonic clown trying to drown the titular toaster ranks among animation’s most terrifying moments, exploiting common childhood fears with sadistic precision.

Perhaps most disturbing was the film’s unflinching look at obsolescence and abandonment—core fears that resonated with children at a primal level. The air conditioner’s mental breakdown and subsequent self-destruction early in the film established that this was no ordinary talking-object movie, but rather an exploration of existential purpose and the fear of being discarded. Parents who selected this based on its cute title and animated format had no warning about its meditations on death, worthlessness, and the horror of being replaced—themes that resonated with children’s deepest insecurities about their place in the world.

These films represent a unique moment in cinema history when the boundaries between children’s and adult content were less defined, creating experiences that shaped—and occasionally scarred—a generation. While modern parents might be shocked at what was marketed to children in these decades, many who grew up with these films look back on them with a strange fondness. Perhaps there was value in these cinematic ambushes after all—preparing children for a world that doesn’t always provide trigger warnings before its most frightening moments. These twelve films, for better or worse, respected children enough to terrify them properly.