Before streaming services and hundreds of cable channels competed for our attention, public television stood as an oasis of thoughtful programming in a desert of commercial entertainment. Those familiar faces that appeared in our living rooms weren’t just television personalities—they were trusted friends who spoke directly to us, never talking down or rushing through complex ideas. With limited production budgets but unlimited passion for their subjects, these educational pioneers created programming that often taught us more about science, art, history, and ourselves than our formal education ever could.

1. Julia Child

The towering presence who transformed American home cooking burst into our living rooms in 1963 with “The French Chef,” bringing sophisticated European techniques to middle-class kitchens across the nation. Child’s distinctive warbling voice and occasional on-air mishaps—like famously dropping a potato pancake before flipping it back into the pan with the cheerful advice that “you’re alone in the kitchen”—made haute cuisine approachable in a way no cookbook ever could. Her genuine enthusiasm and refusal to edit out mistakes created an authenticity rarely seen on television, assuring viewers that perfection wasn’t necessary for delicious results. On top of everything else, All That’s Interesting reports on Child’s extensive career as a spy.

“The French Chef” continued well into the 1970s, followed by other series including “Julia Child & Company” and “Dinner at Julia’s,” each expanding her devoted audience and influencing how Americans thought about food. Beyond specific recipes, Child taught fundamental techniques and the confidence to experiment, transforming home cooking from dutiful drudgery into creative expression. Her greatest gift may have been showing that learning could be joyful rather than serious—a philosophy that defined the best of public television’s educational mission and influenced countless other programs that followed.

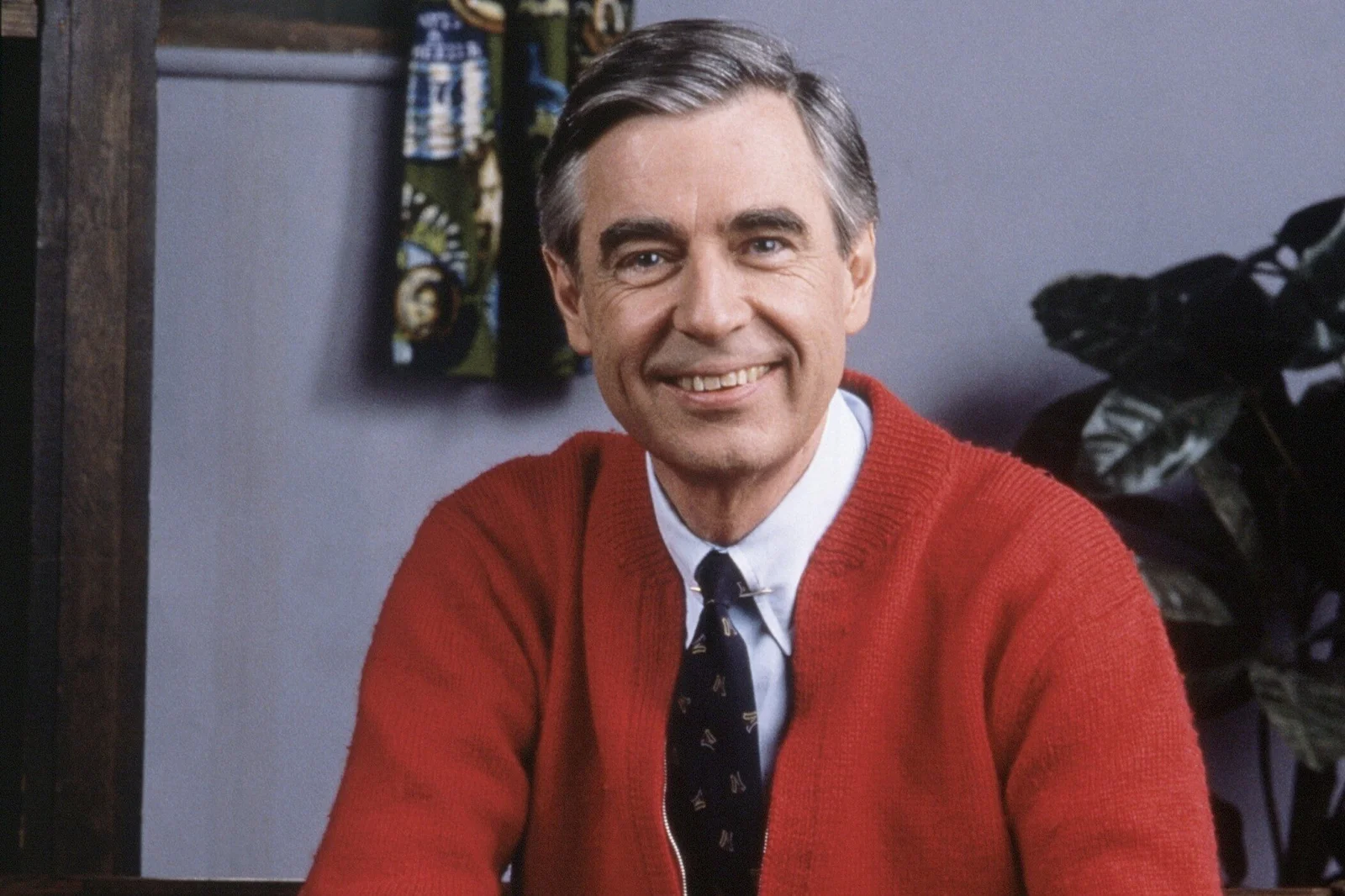

2. Fred Rogers

The gentle soul in the cardigan sweater created “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” in 1968 as a radical alternative to frenetic children’s programming, speaking directly to young viewers with respect and kindness that acknowledged their emotional complexity. Rogers’ slow, deliberate pace and willingness to address difficult topics like death, divorce, and anger provided emotional education rarely found in school curricula or other children’s media. His famous invitation—”Won’t you be my neighbor?”—offered unconditional acceptance that comforted not just children but also parents and grandparents who found themselves humming along to “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.” Biography credits Rogers and his show with forever transforming children’s television.

Rogers’ background in child development and theology informed his carefully constructed program, where even puppet characters in the Land of Make-Believe dealt with realistic emotions and ethical dilemmas. His congressional testimony defending public television funding in 1969—where he recited the lyrics to “What Do You Do With the Mad That You Feel?”—remains one of the most powerful demonstrations of educational television’s unique value. Rogers taught several generations not just social skills but also self-worth, creating a legacy that continues to provide comfort and guidance decades after his final episode.

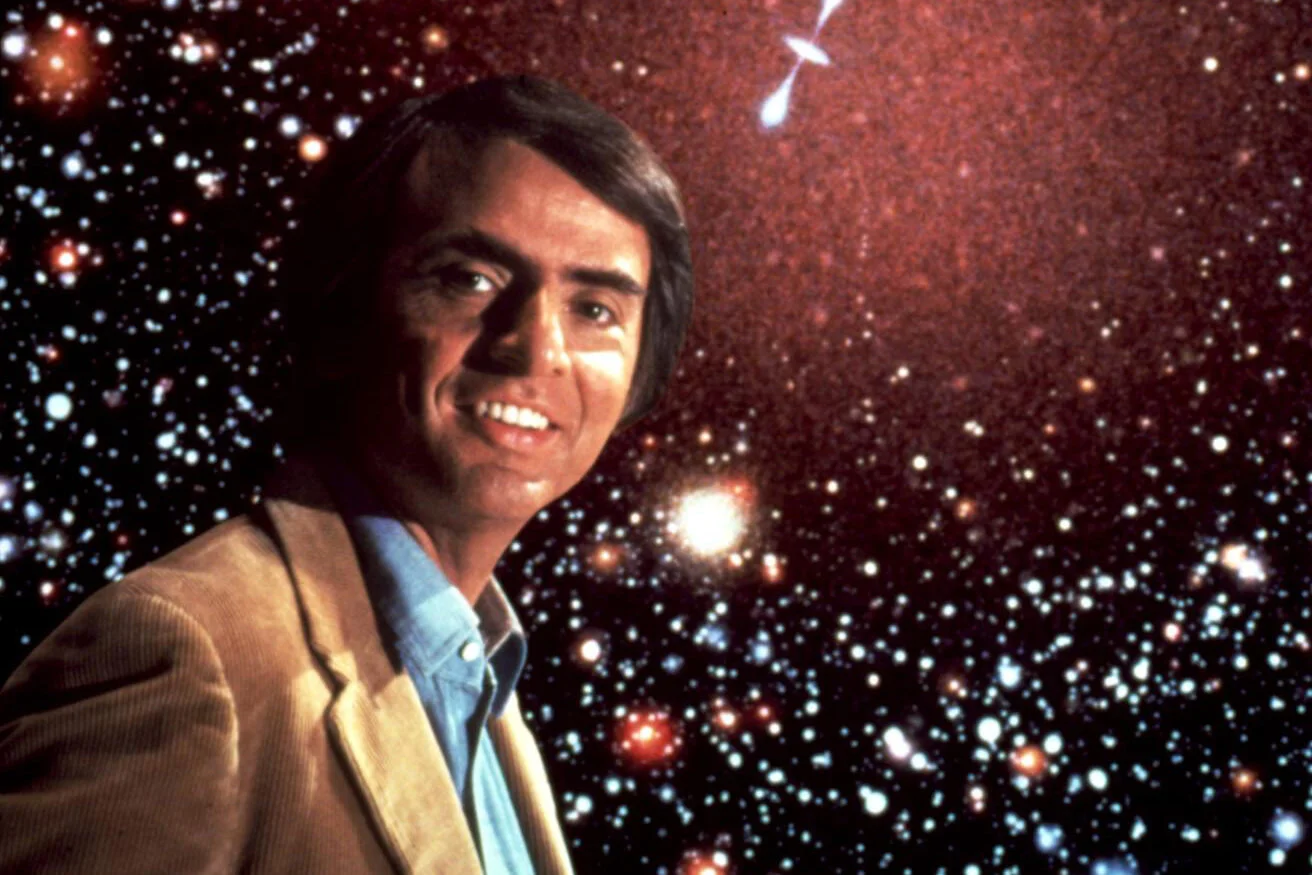

3. Carl Sagan

The charismatic astronomer who made “billions and billions” part of the American lexicon revolutionized science communication with his landmark series “Cosmos” in 1980. Sagan’s poetic descriptions of scientific concepts—delivered with his characteristic pronunciation of “cosmos” and “billions”—made astrophysics and evolutionary biology accessible without simplifying their wonder. His “spaceship of the imagination” carried viewers across the universe and through time, demonstrating how visual storytelling could illuminate abstract concepts that textbooks rendered incomprehensible. Discover Magazine writes that Sagan and his contributions were vital in shaping space science.

The series’ famous opening line—”The cosmos is all that is, or ever was, or ever will be”—established science as a spiritual quest, bridging the perceived gap between scientific inquiry and human meaning. Sagan’s evident wonder at the universe proved more contagious than any classroom lecture could, inspiring countless viewers to pursue careers in science or simply to look at the night sky with greater understanding. His ability to connect scientific concepts to human history and personal meaning demonstrated that education need not be compartmentalized into separate subjects—a holistic approach that defined the best of public television’s educational philosophy.

4. Bob Ross

The soft-spoken artist with the magnificent afro introduced “The Joy of Painting” in 1983, transforming art instruction from technical demonstration into therapeutic experience. Ross’s hypnotic voice describing “happy little trees” and “almighty mountains” created a meditative atmosphere that made painting seem less about technical skill and more about self-expression and emotional well-being. His wet-on-wet technique allowed beginners to create completed landscapes in thirty minutes, providing the immediate gratification often missing from traditional art education.

Though professional artists sometimes criticized his formulaic approach, Ross accomplished something more valuable than teaching fine art technique—he democratized creativity and gave permission to create without fear of failure. His gentle reminders that “there are no mistakes, just happy accidents” offered life philosophy disguised as painting instruction. Ross’s enduring popularity and internet resurrection decades after his death demonstrate how effectively he connected with viewers on an emotional level beyond the mere transmission of skills.

5. Jacques Pépin

The French master chef who served as personal cook to three French heads of state brought classical culinary training to American public television with “The Complete Pépin” in 1970, followed by numerous other series. Pépin’s approach differed significantly from Julia Child’s—where she was exuberant and occasionally chaotic, he was precise and economical in movement, demonstrating techniques honed through formal apprenticeship in France’s top restaurants. His ability to transform basic ingredients into elegant meals without waste or pretension made sophisticated cooking accessible to viewers of all economic backgrounds.

In later series like “Today’s Gourmet” and “Fast Food My Way,” Pépin increasingly emphasized practical home cooking rather than restaurant techniques, adapting his classical training to contemporary American lifestyles. Beyond specific recipes, he taught fundamental principles like knife skills, stock preparation, and ingredient evaluation that empowered viewers to cook independently rather than slavishly following recipes. Pépin’s partnership with Julia Child in “Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home” created some of public television’s most delightful moments, as these two masters good-naturedly disagreed about techniques while demonstrating the joy of cooking as both art and friendship.

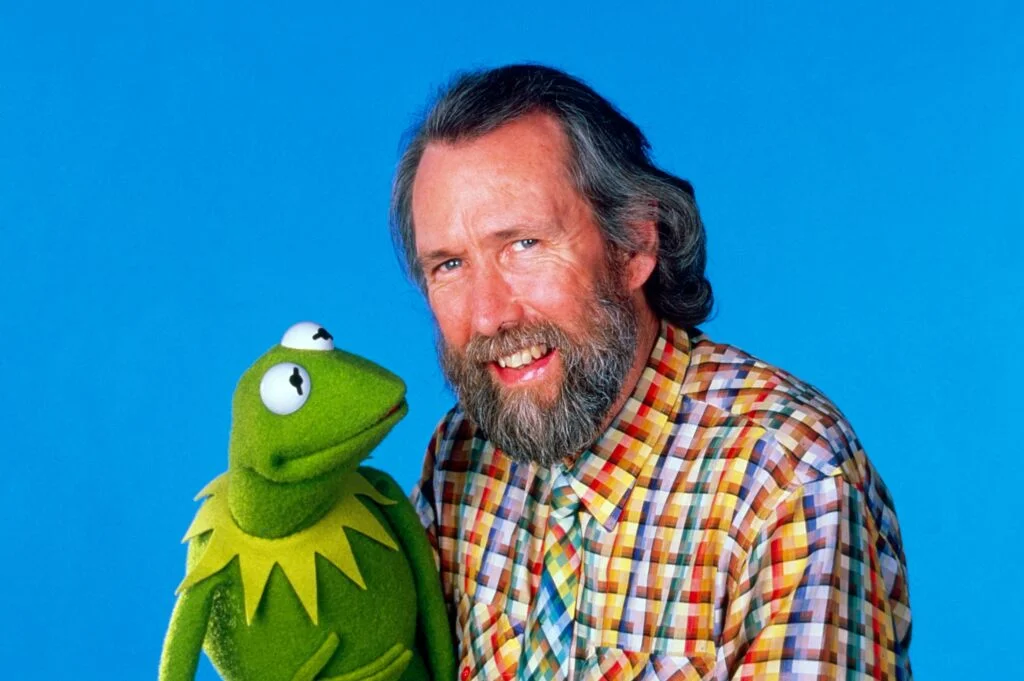

6. Jim Henson

The visionary puppeteer who redefined children’s television revolutionized public broadcasting with his contributions to “Sesame Street” beginning in 1969, creating memorable characters like Kermit the Frog, Ernie, and Big Bird. Henson’s Muppets treated educational content with irreverent humor that appealed to both children and parents, making alphabet lessons and counting practice genuinely entertaining. His technical innovations in puppetry—including the use of monitor playback that allowed puppeteers to see exactly what viewers would see—created a visual style that remains instantly recognizable decades later.

Henson’s later creation “The Muppet Show” demonstrated his range beyond educational content, though it maintained the gentle humor and emotional intelligence that characterized all his work. His collaboration with Frank Oz produced some of television’s most beloved character pairs (Bert and Ernie, Kermit and Miss Piggy), teaching cooperation and conflict resolution through comedy. Henson’s tragic early death in 1990 cut short a remarkable creative life, but his characters continue educating new generations through the foundation and production company that bear his name.

7. Bill Nye

The energetic engineer in the bow tie made science irresistibly cool with “Bill Nye the Science Guy,” which debuted in 1993 and quickly became a classroom staple. Nye’s fast-paced demonstrations and quirky humor created science lessons that children voluntarily watched after school, memorizing his catchphrases and theme song. His commitment to hands-on experimentation encouraged students to replicate demonstrations at home, extending the educational experience beyond passive viewing.

Each episode focused on a single scientific concept explored through multiple experiments, reinforcing key principles through repetition and application. Nye’s genuine enthusiasm—often expressed through his trademark exclamation “Science rules!”—made his passion for discovery contagious among viewers who might otherwise have found science intimidating or boring. His later advocacy work on climate change and evolution demonstrated how childhood science education could translate into adult scientific literacy—the ultimate goal of educational television.

8. James Burke

The British science historian created intellectual connections across disciplines with his landmark series “Connections” in 1978, followed by “The Day the Universe Changed” in 1985. Burke’s central insight—that technological developments occur through unexpected links between seemingly unrelated fields—challenged the linear progression narrative of traditional history education. His breathless narration as he physically raced between locations demonstrated the excitement of intellectual discovery, making history and science feel like detective work rather than memorization.

Burke’s famous demonstrations—like broadcasting from inside an echo chamber to explain radar development or standing in a medieval field to describe agricultural innovations—used location filming to make abstract concepts concrete. His overarching message about interconnectedness of knowledge directly contradicted the compartmentalized subject approach of traditional education, encouraging viewers to think across disciplinary boundaries. Burke’s intellectual ambition and faith in viewers’ intelligence exemplified public television’s commitment to challenging content that commercial networks might have deemed too complex for mainstream audiences.

9. Margaret Mead

The pioneering anthropologist who introduced cross-cultural perspectives to television audiences in the 1970s, challenging American viewers to question their cultural assumptions.

As one of the few female scientific authorities on television, she provided an important role model while making complex anthropological concepts accessible.

10. Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer

The journalistic duo who created “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report” in 1975 (later “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” and now “PBS NewsHour”) established a standard for thoughtful news coverage that contrasted sharply with the increasingly sensationalized commercial broadcasts. Their revolutionary format—devoting extended segments to single issues rather than jumping between brief stories—allowed for nuance and context absent from sound-bite journalism. Their respectful interview style, characterized by genuinely open-ended questions and patient listening, elicited substantive responses rather than rehearsed talking points.

When the program expanded to a full hour in 1983, it became television’s first hour-long daily news broadcast, allowing even greater depth and complexity. MacNeil and Lehrer’s commitment to political balance and factual accuracy established a reputation for trustworthiness that continues under subsequent anchors. Their approach to news as education rather than entertainment taught viewers to expect substance rather than sensation from journalism—a lesson increasingly valuable in today’s fragmented media landscape.

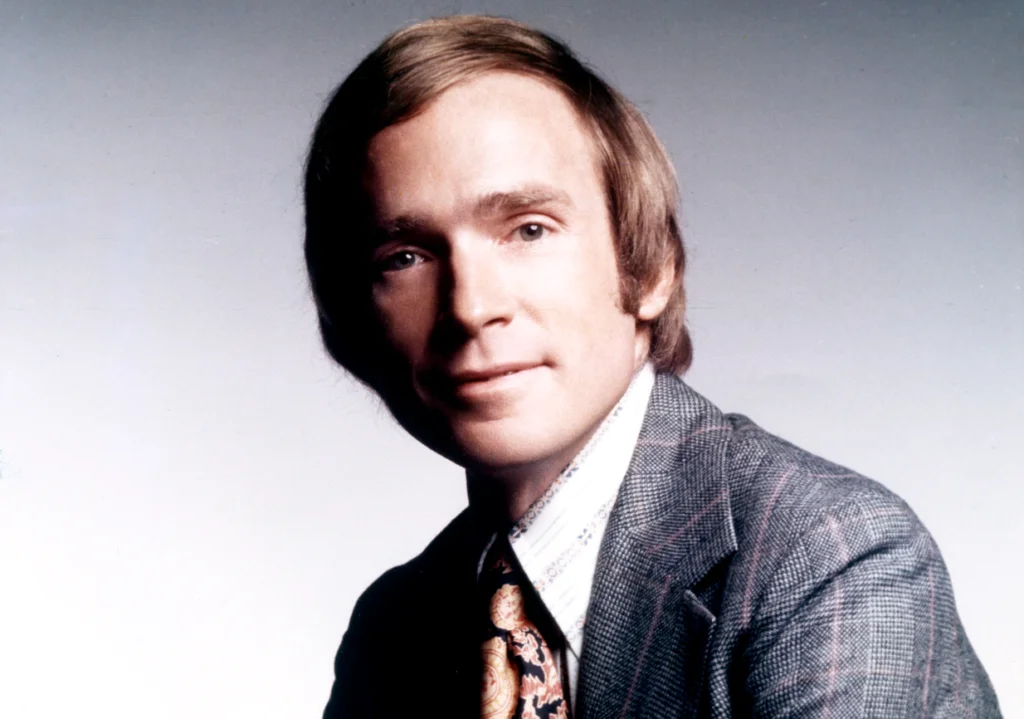

11. Dick Cavett

The sophisticated talk show host whose PBS version of “The Dick Cavett Show” featured in-depth conversations with cultural figures rarely given serious attention on commercial television.

His literary intelligence and willingness to allow conversations to unfold naturally created interviews of unprecedented depth that now serve as valuable historical documents.

12. Marshall Efron

The subversive consumer advocate brought countercultural sensibility to public television with “The Great American Dream Machine” and “Consumer Survival Kit” in the early 1970s, using humor to deliver pointed criticism of commercial products and advertising. Efron’s portly presence and deadpan delivery created memorable segments like his famous demonstration of artificial ingredients in commercial ice cream, where he created a non-melting “ice cream” from chemicals and petroleum products. His willingness to name specific brands and products provided consumer education rarely found in schools or mainstream media.

Efron’s approach combined entertainment with genuine consumer advocacy, teaching viewers to question advertising claims and understand product labeling. His segments on food additives, appliance safety, and deceptive marketing predated the consumer advocacy movement that would later gain mainstream acceptance. Though less remembered than some public television personalities, Efron’s influence on consumer awareness and critical media literacy continues in today’s product review culture and food transparency movements.

The educational pioneers of public television shared a fundamental belief that their viewers were intelligent, curious, and deserving of respect—assumptions not always evident in commercial programming or, sadly, in some classrooms. Their lasting legacy lies not just in specific facts or skills they taught, but in modeling a way of engaging with knowledge that emphasized wonder, connection, and personal relevance. While formal education sometimes reduced learning to standardized tests and memorization, these beloved television teachers reminded us that true education engages heart and spirit alongside intellect—a holistic approach that continues to distinguish the best of public broadcasting from its commercial counterparts.