Remember when movies didn’t need to wrap everything up in a neat little bow? The 1960s gave us some of the most daring, provocative, and downright shocking film endings that left audiences buzzing in theater lobbies long after the credits rolled. These weren’t your typical Hollywood happy endings – they were bold, uncompromising, and sometimes brutally honest about the complexities of life.

Looking back at these cinematic gems, it’s fascinating to see how much our expectations have changed. Today’s audiences expect clear resolutions, moral victories, and characters who learn valuable lessons. But back then, filmmakers weren’t afraid to leave us hanging, challenge our assumptions, or send us home with more questions than answers.

1. Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

The machine-gun finale of Arthur Penn’s groundbreaking crime drama shocked moviegoers with its unprecedented violence and ambiguous morality. Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty’s iconic outlaws meet their end in a hail of bullets that seems to go on forever, filmed in slow motion that makes every impact feel visceral and real. The camera lingers on their bullet-riddled bodies with an unflinching gaze that would make modern focus groups squirm in their seats.

What really wouldn’t fly today is how the film makes us sympathize with these bank robbers right up until their violent end, never offering the moral clarity that contemporary audiences crave. There’s no redemption arc, no last-minute epiphany about the error of their ways – just two people who lived by violence dying by violence. Modern test screenings would probably demand a scene where Bonnie expresses regret or Clyde tries to surrender, but Penn refused to give audiences that comfort.

2. The Graduate (1967)

Mike Nichols ended this cultural touchstone with Benjamin and Elaine sitting on that bus, their initial joy at escaping together slowly fading into uncertainty and doubt. The camera holds on their faces as the reality of what they’ve just done – and what comes next – begins to sink in. That final shot, with its uncomfortable silence and dawning realization, would have modern studio executives demanding reshoots.

Today’s audiences expect romantic comedies to end with couples gazing lovingly into each other’s eyes, planning their future together. Instead, The Graduate gives us two people who suddenly realize they might have made a terrible mistake, sitting in awkward silence as the bus carries them toward an uncertain future. Focus groups would probably hate that lingering sense of “what have we done?” that replaces the expected happily-ever-after moment.

3. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Charlton Heston’s Taylor finally escapes the ape civilization only to discover the twisted remains of the Statue of Liberty buried in the sand, realizing he’s been on post-apocalyptic Earth all along. His anguished cry about mankind’s self-destruction provides one of cinema’s most powerful and hopeless endings. The revelation that humans destroyed their own civilization offers no hope for redemption or rebuilding – just pure, existential despair.

Modern blockbusters would never dare end on such a note of complete hopelessness, especially in a big-budget science fiction film. Today’s version would probably show Taylor finding other human survivors or discovering a way to rebuild civilization, giving audiences something to feel good about. But Franklin J. Schaffner’s ending offers no such comfort – just the brutal truth that we are our own worst enemy, delivered with uncompromising bleakness.

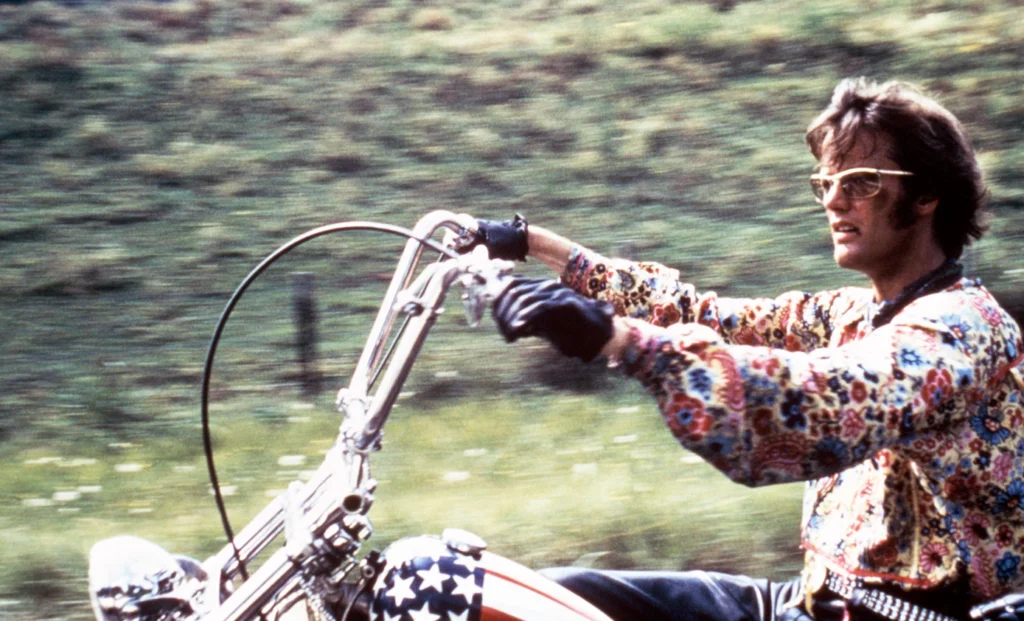

4. Easy Rider (1969)

Dennis Hopper’s counterculture road movie ends with Billy and Wyatt getting gunned down by rednecks for no other reason than their long hair and lifestyle choices. The senseless violence comes out of nowhere, cutting short their journey of self-discovery with brutal suddenness. There’s no final confrontation, no chance for our heroes to defend themselves – just random hatred and death on a lonely highway.

Contemporary audiences would demand justice for these characters, expecting the killers to be caught or at least identified. Modern storytelling conventions require that violence serve a narrative purpose, but Easy Rider’s ending suggests that sometimes bad things happen to people for no good reason at all. The film’s refusal to provide closure or meaning to their deaths would frustrate today’s viewers who want to understand why tragedy strikes and what it all means.

5. Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Joe Buck’s dream of making it big in Florida dies along with his friend Rizzo on that Greyhound bus, leaving our naive cowboy alone and directionless in a world that has consistently chewed him up and spit him out. The film ends with Joe holding his deceased companion, finally understanding that his dreams of easy money and success were just illusions. There’s no suggestion that he’s learned valuable lessons that will help him succeed – just the reality that life can be cruel and dreams often die hard deaths.

Modern audiences would expect Joe to honor his friend’s memory by making something of himself, perhaps using the hard-won wisdom from his experiences to find success and meaning. Instead, John Schlesinger leaves us with a broken man who has lost the only real relationship he ever had, facing an uncertain future with no clear path forward. Today’s version would probably end with Joe starting fresh, but the original offers no such hopeful resolution.

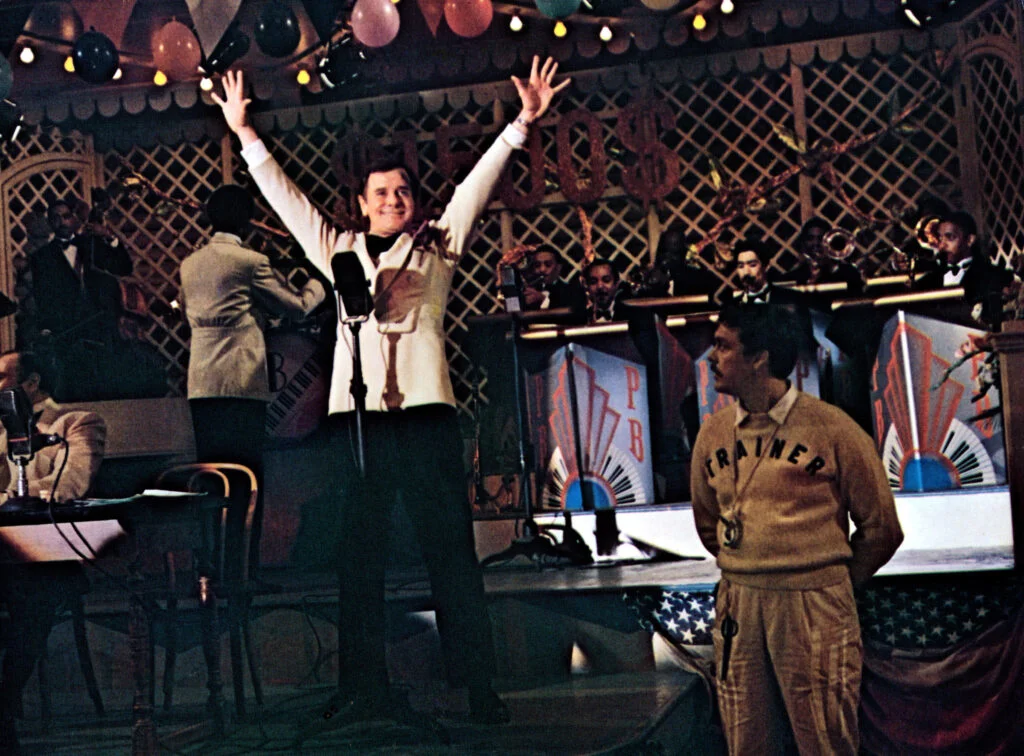

6. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)

Sydney Pollack’s depression-era drama ends with Robert putting Gloria out of her misery, literally shooting her as an act of mercy after their brutal dance marathon experience breaks her spirit completely. The film’s final moments show Robert being arrested for murder, even though his actions were motivated by compassion for someone who had given up on life entirely. The ending suggests that sometimes kindness looks like cruelty, and mercy can be indistinguishable from murder.

Today’s audiences would struggle with the moral ambiguity of euthanasia presented without clear ethical guidelines or comfortable answers. Modern films would likely include scenes showing Gloria’s family or background to help us understand her desperation, or provide Robert with a legal defense that makes his actions seem more justified. But Pollack refuses to make it easy, presenting a complex moral situation without offering simple solutions or clear-cut heroes and villains.

7. Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Roman Polanski’s psychological horror masterpiece ends with Rosemary accepting her role as mother to the Antichrist, gently rocking her demonic offspring after discovering the truth about her pregnancy. Rather than rejecting the child or fleeing in horror, she embraces her maternal instincts even knowing what her baby represents. The final image of her singing a lullaby to Satan’s son would send modern audiences into fits of confusion and moral outrage.

Contemporary horror films would never dare suggest that a mother could accept such an evil child, expecting instead that she would sacrifice herself to save the world from this threat. Today’s version would probably end with Rosemary finding a way to destroy the baby or herself, choosing the greater good over maternal love. But Polanski’s ending suggests that maternal bonds transcend even ultimate evil, a concept that would make modern focus groups extremely uncomfortable.

8. The Wild Bunch (1969)

Sam Peckinpah’s brutal Western ends with Pike Bishop and his aging outlaws choosing to go out in a blaze of glory rather than fade away quietly, resulting in a massacre that claims everyone involved. The final shootout is lengthy, violent, and ultimately pointless – these men die for no cause greater than their own stubborn refusal to change with the times. Their deaths accomplish nothing except to eliminate the last of their kind from a world that no longer has room for them.

Modern audiences would expect these characters to find redemption through sacrifice, perhaps dying to save innocent people or to right some terrible wrong from their past. Instead, Peckinpah gives us men who die simply because they’re too proud and set in their ways to adapt to a changing world. Today’s westerns would probably show them finding peace or passing on their wisdom to a younger generation, but The Wild Bunch offers no such comfort or meaning to their violent end.

9. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction epic ends with Dave Bowman’s transformation into the Star Child, a sequence so abstract and open to interpretation that audiences left theaters arguing about what they had just witnessed. The film provides no explanation for the monoliths, no clear resolution to humanity’s evolutionary journey, and no easy answers about our place in the universe. Kubrick deliberately crafted an ending that raises more questions than it answers, trusting audiences to grapple with cosmic mysteries.

Today’s science fiction blockbusters would never dare end with such ambiguity, expecting instead clear explanations for alien technology and humanity’s destiny among the stars. Modern test audiences would demand to know who built the monoliths, why they’re helping humanity evolve, and what the Star Child plans to do next. But Kubrick’s ending suggests that some questions are too big for simple answers, a philosophy that would frustrate contemporary viewers accustomed to detailed exposition and tidy resolutions.

10. Blow-Up (1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s mystery ends with photographer Thomas realizing that reality itself might be subjective, as he watches mimes play invisible tennis and actually hears the ball being hit. The possible murder he thought he photographed may or may not have happened, and the film suggests that truth is less important than perception. The final image of Thomas disappearing from the frame entirely implies that identity itself might be an illusion.

Modern audiences would demand clear answers about whether the murder actually occurred, expecting forensic evidence or police investigation to resolve the mystery definitively. Today’s version would probably include flashbacks showing exactly what happened, removing all ambiguity about the central crime. But Antonioni’s ending suggests that absolute truth might be impossible to achieve, a concept that would leave contemporary viewers feeling cheated and confused.

11. The Odd Couple (1968)

Gene Saks’ adaptation of Neil Simon’s play ends with Felix and Oscar going their separate ways after their friendship reaches a breaking point, but without the heartwarming reconciliation that modern audiences would expect. Felix moves in with the upstairs neighbors, the Pigeon sisters, while Oscar returns to his messy bachelor lifestyle, and neither man seems to have learned much from their experience living together. The film suggests that some personality conflicts are simply irreconcilable, no matter how much affection exists between people.

Contemporary comedies would never let these beloved characters part ways without a touching scene where they realize how much they mean to each other and find a way to make their friendship work. Today’s version would probably end with Felix and Oscar finding a compromise that allows them to remain roommates, or at least close friends who regularly spend time together. But the original ending acknowledges that sometimes people just aren’t compatible, even when they genuinely care about each other.

12. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

George Roy Hill’s beloved Western ends with Butch and Sundance surrounded by Bolivian soldiers, charging out of their hideout into certain death as the screen freezes on their final moment of defiant action. We never see them actually die, but the overwhelming odds make their fate inevitable, turning their last stand into a moment of tragic heroism. The freeze-frame ending preserves them forever in that instant of courage, refusing to show the brutal reality of their deaths.

Modern audiences would probably demand either a miraculous escape or at least a heroic death scene that shows them taking down multiple enemies before falling, making their sacrifice meaningful and satisfying. Today’s version might even include a twist revealing that they somehow survived, setting up a sequel or at least providing hope for their future. But Hill’s ending acknowledges that even beloved outlaws must eventually face the consequences of their choices, preserved in our memory at their most heroic moment rather than in death.

These twelve endings remind us of a time when filmmakers trusted audiences to handle complexity, ambiguity, and uncomfortable truths. They didn’t feel the need to explain everything or tie up every loose thread, understanding that the best stories often leave us with something to think about long after we’ve left the theater. While modern cinema has its own merits, there’s something to be said for the bold storytelling choices that made the 1960s such a revolutionary decade in film history.

This story ’60s Movie Endings That Would Never Fly with Today’s Audiences was first published on Takes Me Back.