Jerry Lewis wasn’t just a comedian—he was a comedic force of nature who redefined physical humor for generations to come. With his rubber-faced expressions, manic energy, and singular comedic vision, Lewis created characters that no other performer could have possibly embodied. From his early partnership with Dean Martin to his later solo career and directorial achievements, Lewis left an indelible mark on comedy that continues to influence entertainers today.

1. Professor Julius Kelp in “The Nutty Professor” (1963)

As the socially awkward, buck-toothed scientist Professor Julius Kelp, Lewis delivered what many critics consider his definitive performance. Kelp’s transformation into the suave but obnoxious Buddy Love allowed Lewis to showcase his remarkable range, playing both the sympathetic underdog and the insufferable ladies’ man with equal conviction. The film’s exploration of dual identity served as a metaphor for Lewis’s own complex personality—the vulnerable, childlike performer versus the controlling artistic perfectionist. Naturally, when MeTV ranked the best Jerry Lewis movies, this one ranked very well.

This role demonstrated Lewis’s meticulous approach to character development, with the actor spending months perfecting Kelp’s distinctive walk, voice, and mannerisms. The film, which Lewis also directed and co-wrote, has been preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for its cultural significance. Eddie Murphy’s 1996 remake paid homage to Lewis’s original creation but could never capture the peculiar magic that made Lewis’s version a masterpiece of comedic vulnerability.

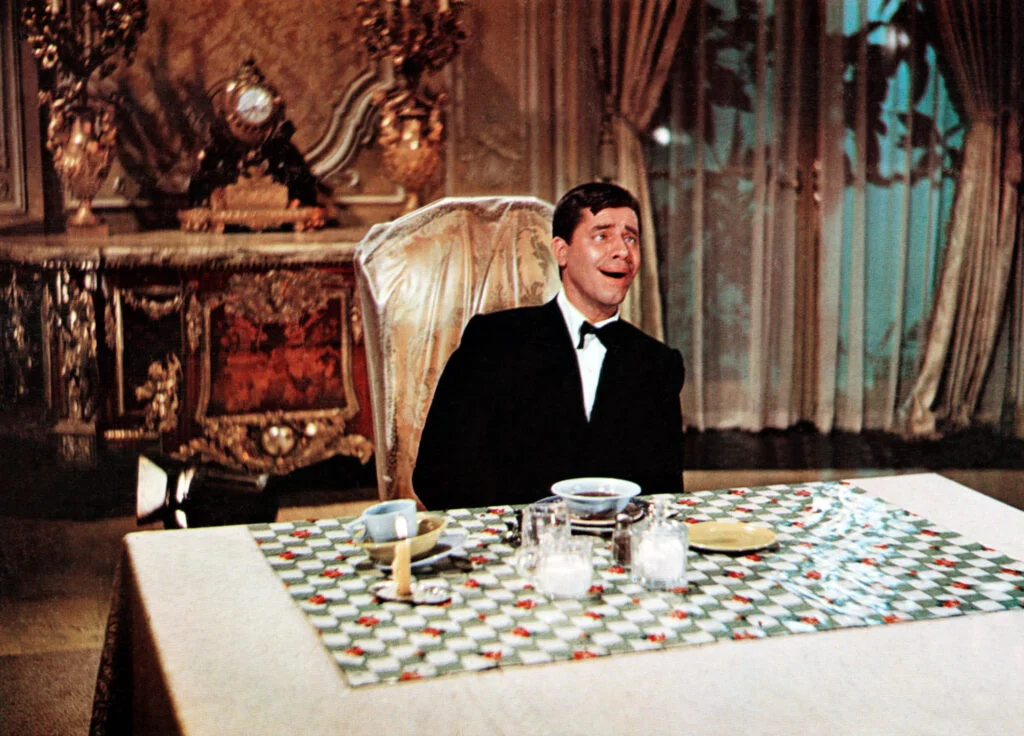

2. Cinderfella in “Cinderfella” (1960)

Lewis’s gender-flipped take on the classic Cinderella tale cast him as the mistreated stepson who transforms into a dashing gentleman with the help of his fairy godfather (Ed Wynn). The film’s grand ballroom entrance scene—where Lewis descends an enormous staircase in slow motion to “Cinder-Fella”—became one of the most memorable visual gags of his career. The physical demands of this sequence were so taxing that Lewis was reportedly hospitalized after filming it. IMDb has some additional bits of information that makes Lewis’s performance even more astounding.

Director Frank Tashlin crafted this Technicolor fantasy specifically for Lewis’s unique talents, allowing him to blend childlike innocence with moments of surprising emotional depth. Paramount initially wanted the film released for Christmas 1960, but Lewis successfully fought to delay it, believing the film deserved a better marketing strategy. Critics praised Lewis’s performance for adding unexpected poignancy to what could have been merely silly slapstick, establishing “Cinderfella” as one of his most enduring family-friendly features.

3. Stanley the Bellboy in “The Bellboy” (1960)

In what would become his directorial debut, Lewis played Stanley, a non-speaking bellhop causing havoc throughout the luxurious Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach. The brilliance of this performance lies in Lewis’s commitment to purely visual comedy, creating a character who communicates entirely through physical expression and pantomime. Lewis famously shot the film during the day while performing at the hotel’s nightclub each evening, completing production in just four weeks. According to Classic Movie Hub, Lewis has way fewer lines than one would think, but he sure makes them count.

The film’s episodic structure allowed Lewis to construct a series of self-contained comedic setpieces showcasing his extraordinary physical control and timing. Film historians often cite “The Bellboy” as a pivotal moment in Lewis’s career, marking his transition from performer to auteur with complete creative control. Lewis later revealed that the character was inspired by the silent film work of Stan Laurel, who was originally asked to consult on the film but passed away before production began.

4. Herbert H. Heebert in “The Ladies Man” (1961)

As Herbert H. Heebert, a heartbroken young man who takes a job as the only male employee in a boarding house for women, Lewis created a character defined by his comical discomfort around the opposite sex. The film featured an extraordinary set—a massive cutaway dollhouse-style boarding house that took up two sound stages and cost $350,000 to build in 1961 (equivalent to about $3.5 million today). Lewis’s innovative directorial choices included a famous choreographed sequence where the camera glides through multiple rooms of the house in one continuous shot.

Herbert’s exaggerated clumsiness and social anxiety provided the perfect vehicle for Lewis’s brand of physical comedy, with elaborate pratfalls and facial contortions that became his trademark. Film scholars have noted how Lewis used the character to explore male anxiety in the changing social landscape of the early 1960s. Lewis later said the elaborate production design nearly caused Paramount executives to shut down production until they saw the first week’s footage and realized his artistic vision.

5. Morty S. Tashman in “The Errand Boy” (1961)

Lewis played Morty Tashman, an inept paperhanger hired by a movie studio executive to spy on wasteful spending, only to cause exponentially more damage himself. The film’s most iconic scene features Morty pretending to be a powerful executive while pantomiming to Count Basie’s “Blues in Hoss’ Flat,” a masterclass in comedic timing that comedians still study today. The performance showcased Lewis’s exceptional ability to synchronize movement with music, a skill he had honed during his years in vaudeville and nightclubs.

As both star and director, Lewis used the movie-studio setting to comment on Hollywood’s excesses while demonstrating his encyclopedic knowledge of film history through visual references and homages. Studio records reveal that Lewis insisted on recording separate international soundtracks where he redubbed his own voice in phonetic Japanese, German, French, and Italian rather than using voice actors. Contemporary directors including Martin Scorsese and Jean-Luc Godard have cited this film as influential on their understanding of visual comedy and film language.

6. Sidney Pythias in “The Delicate Delinquent” (1957)

As Sidney Pythias, a misunderstood janitor mistaken for a juvenile delinquent who forms an unlikely bond with a police officer (Darren McGavin), Lewis delivered his first solo leading role after splitting with Dean Martin. The character’s transformation from terrified misfit to proud police cadet allowed Lewis to balance humor with surprising emotional resonance. The film was originally written for the Martin and Lewis team, with Sidney’s relationship with the cop serving as a substitute for the familiar Lewis-Martin dynamic.

Lewis demonstrated remarkable restraint in this performance, toning down his typically manic energy to create a more three-dimensional character audiences could genuinely root for. Film historians note that “The Delicate Delinquent” marked an important transition in Lewis’s screen persona, moving from purely comedic sidekick to a more complex leading man capable of carrying a film’s emotional weight. Despite mixed critical reception, the film was a commercial success that proved Lewis could thrive without Martin, grossing over $6 million against a modest production budget.

7. Eugene Fullstack in “Boeing Boeing” (1965)

As the neurotic American journalist Eugene Fullstack, Lewis played the perfect foil to Tony Curtis’s smooth-talking playboy in this adaptation of the French stage farce. Eugene’s gradually increasing confidence throughout the film showcased Lewis’s ability to evolve a character beyond simple caricature, culminating in a memorably chaotic climax. Lewis deliberately calibrated his performance to complement rather than overshadow Curtis, demonstrating his often underappreciated skills as a collaborative ensemble player.

Director John Rich praised Lewis’s professionalism and willingness to adjust his performance style to fit the sophisticated tone of the material. The film’s international setting—Paris—allowed Lewis to indulge in cultural misunderstandings that had become a staple of his comedy. Behind-the-scenes accounts reveal that Lewis studied French comedy traditions extensively before filming, incorporating elements of boulevard theater timing into his performance while still maintaining his distinctively American comedic persona.

8. Willard Fillmore in “The Patsy” (1964)

Lewis portrayed Willard Fillmore, a hotel bellhop transformed into a celebrity by a team of showbiz professionals attempting to replace their recently deceased star. The role allowed Lewis to satirize his own rise to fame while demonstrating his versatility through scenes where Willard attempts (and catastrophically fails) at various entertainment specialties. Lewis’s direction included innovative technical achievements, including a memorable sequence where a camera follows him through multiple rooms in a single shot years before similar techniques became common.

The character’s journey from complete incompetence to accidental success served as a pointed commentary on celebrity manufacture in the entertainment industry. Film scholars have noted the autobiographical elements in this performance, with Lewis effectively playing a version of himself before he developed his skills. Production documents reveal that Lewis personally supervised every technical aspect of the film, from lighting design to sound mixing, cementing his reputation as one of Hollywood’s most controlling—and technically knowledgeable—comedy auteurs.

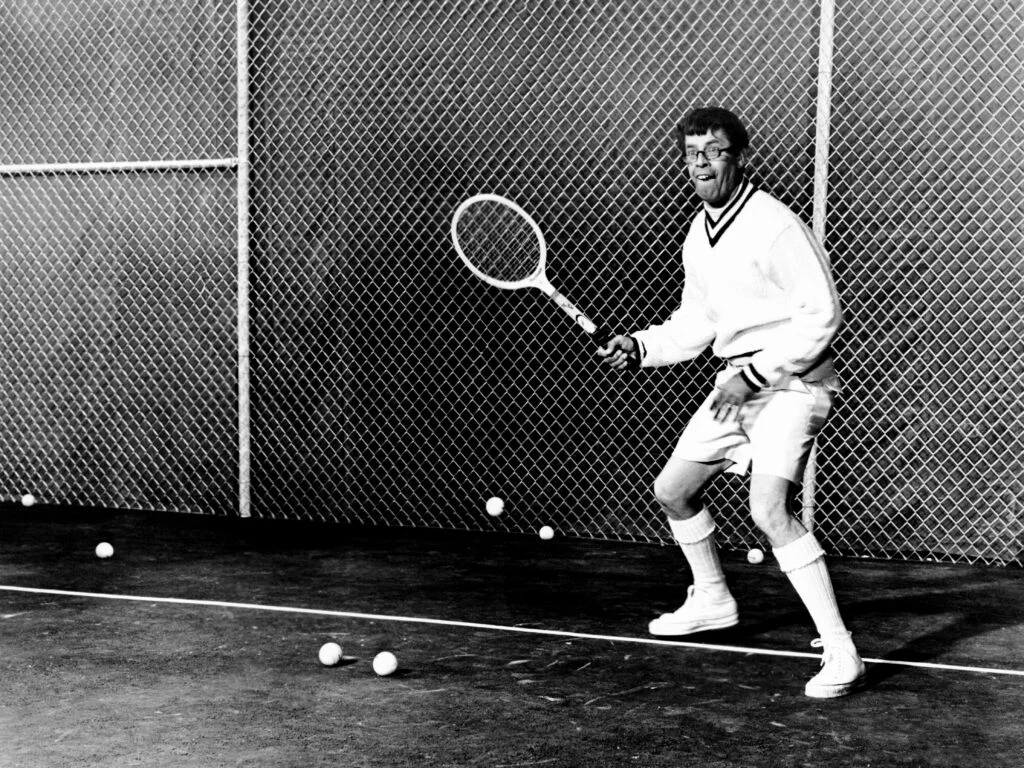

9. Myron Mertz in “Who’s Minding the Store?” (1963)

As Myron Mertz, a dog walker hired to work in a department store by his girlfriend’s mother (who secretly owns the store and wants to humiliate him), Lewis created some of his most memorable physical comedy sequences. The film’s typewriter pantomime scene, where Myron “types” in perfect synchronization with a jazzy soundtrack, demonstrated Lewis’s extraordinary physical precision and musical timing. Director Frank Tashlin, a former animator, designed many sequences as essentially live-action cartoons built around Lewis’s unique physical capabilities.

Lewis’s performance balanced sympathetic underdog qualities with moments of surprising dignity when Myron stands up for himself against his manipulative potential mother-in-law. Department store records indicate that retail sales of items featured prominently in the film increased dramatically following its release, particularly vacuum cleaners after Lewis’s famous battle with an industrial model. Modern comedians including Jim Carrey and Jack Black have specifically cited this performance as influential on their approach to physical comedy.

10. Warren Nefron in “Cracking Up” (1983)

In his final directorial effort, Lewis played Warren Nefron, a man so plagued by catastrophic clumsiness and bad luck that he attempts suicide, only to discover his therapist is equally disturbed. The film’s opening sequence—a masterclass in sustained physical comedy—shows Warren destroying an entire apartment through a cascading series of accidents. Lewis shot this scene when he was 57 years old, demonstrating his continued commitment to physically demanding comedy despite chronic back pain from years of pratfalls.

The film’s episodic structure allowed Lewis to revisit various character types from throughout his career, serving as a kind of summation of his comedic philosophy. Though commercially unsuccessful upon release, “Cracking Up” has been reappraised by French film critics in particular as a darkly existential comedy addressing themes of human dysfunction and psychological fragility. Behind-the-scenes accounts reveal that Lewis personally financed aspects of post-production when the studio attempted to cut his final edit, showing his lifelong determination to maintain creative control of his work.

11. Norman Phiffier in “The Disorderly Orderly” (1964)

As Jerome Littlefield, a well-meaning but disaster-prone hospital orderly with “neurotic identification empathy” (feeling the symptoms of any illness described to him), Lewis created a character perfectly suited to the medical setting’s comedic possibilities. The film’s gurney chase sequence—where Jerome loses control of a patient’s bed down San Francisco’s steep hills—became one of Lewis’s most recognized set pieces. Lewis performed many of his own stunts for these sequences despite having fractured his back just years earlier, requiring him to wear a special brace under his costume.

Working again with director Frank Tashlin, Lewis balanced broad physical gags with moments of genuine tenderness when interacting with patients, showcasing his underappreciated range as a performer. Medical professionals have noted that beneath the slapstick, the film actually addresses serious healthcare themes including patient dignity and caregiver burnout. Lewis later revealed that he spent two weeks observing actual hospital orderlies before filming, incorporating authentic details into his performance while exaggerating them for comic effect.

12. Gerald Clamson/Syd Valentine in “The Big Mouth” (1967)

Lewis played dual roles as mild-mannered accountant Gerald Clamson and his lookalike, gangster Syd Valentine, in this comedy thriller involving stolen diamonds and gangland pursuit. The film’s technical achievements—including scenes where Lewis appeared twice through split-screen effects—were groundbreaking for their time and largely supervised by Lewis himself. Lewis insisted on performing both characters with distinctly different physical mannerisms, voices, and even walking styles to ensure viewers could tell them apart even without dialogue.

The film’s memorable Japanese fishing village sequences showcased Lewis’s controversial approach to ethnic humor, with characterizations that modern audiences find problematic but were common in comedy of the era. Production records indicate that Lewis meticulously storyboarded every scene in pre-production, creating over 2,000 individual drawings to communicate his vision to the crew. Despite mixed critical reception, film historians recognize the movie as an important technical achievement in Lewis’s directorial career, particularly its innovative use of underwater photography.

13. Helmut Doork in “The Day the Clown Cried” (Unreleased, 1972)

Though never officially released, Lewis’s performance as Helmut Doork—a German circus clown imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp and forced to lead children to gas chambers—has become legendary in film history. Based on limited accounts from those who’ve seen footage, Lewis reportedly delivered a haunting dramatic performance unlike anything in his public filmography. Lewis maintained almost complete control over the project, serving as director, producer, and star while financing much of the production himself when initial funding collapsed.

After completing principal photography, Lewis shelved the film, reportedly dissatisfied with the results and concerned about the appropriateness of the material. The Library of Congress now holds a copy that cannot be screened until 2024, according to Lewis’s donation agreement. Harry Shearer, one of the few to see a rough cut, famously described it as “drastically wrong” while others who worked on the production defended Lewis’s sincere intentions to address Holocaust history through the lens of a tragic clown figure.

14. Professor John Frink Sr. in “The Simpsons” (2003)

Lewis made a memorable animated appearance as Professor Frink’s father in the “Treehouse of Horror XIV” episode, bringing his distinctive vocal mannerisms to a character explicitly modeled after Julius Kelp from “The Nutty Professor.” The performance won Lewis his only Emmy Award and introduced his comedic style to a new generation of viewers. Lewis recorded his lines during a period of serious health challenges, demonstrating his lifelong commitment to performance even while dealing with personal difficulties.

The character’s blend of mad scientist tropes and Lewis’s signature vocal patterns created a perfect synthesis of animation and the comedian’s established persona. Series creator Matt Groening reported that Lewis improvised approximately 40% of his dialogue during the recording session, leaving the writing staff in awe of his creative spontaneity. This late-career voice performance exemplified Lewis’s continued cultural relevance decades after his commercial peak, cementing his legacy across multiple entertainment mediums and generations.

From bucktoothed professors to hapless bellboys, Jerry Lewis created an unmatched gallery of unforgettable characters that pushed the boundaries of physical comedy while often containing surprising emotional depth. His unique combination of technical precision, boundless energy, and childlike vulnerability produced performances that remain instantly recognizable decades later. Though sometimes dismissed by American critics during his lifetime, Lewis’s artistic legacy continues to influence comedians worldwide who recognize what audiences always knew—there was simply nobody else who could do what Jerry Lewis did.