1. Norman Bates (Psycho, 1960)

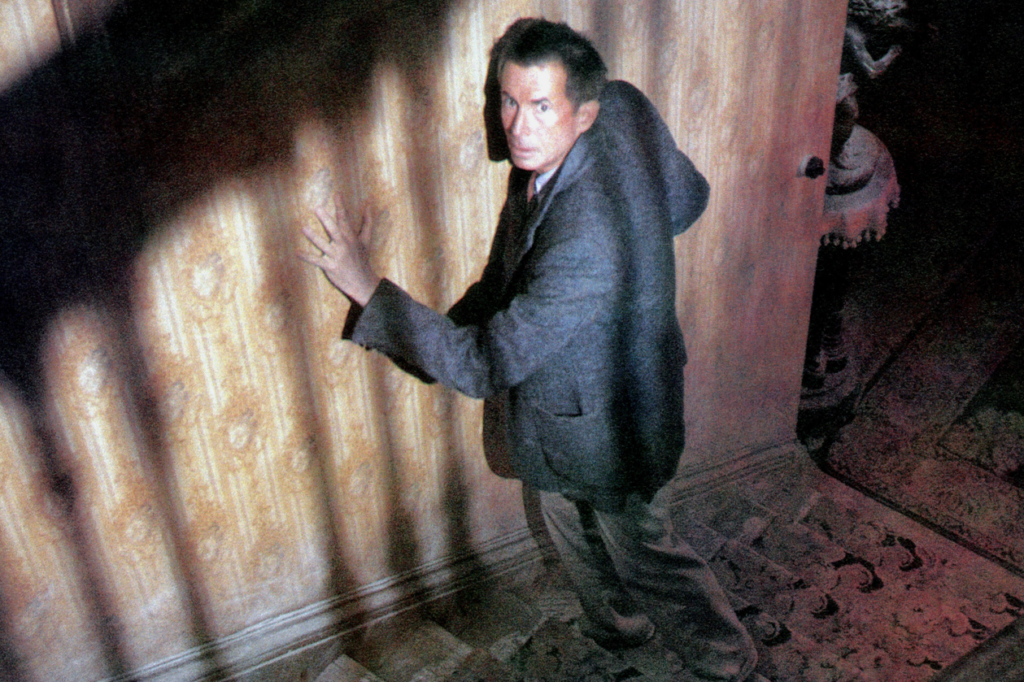

Norman Bates did not look like a movie monster, and that was exactly the problem. He was polite, awkward, and soft spoken, the kind of man you might feel bad for after a brief conversation. That gentle surface made his sudden violence feel deeply unsettling. Audiences had never quite seen a villain who felt so painfully human.

What made Bates terrifying was the sense that something was quietly wrong long before anything actually happened. Alfred Hitchcock let the tension build in tiny gestures, nervous smiles, and half finished thoughts. By the time the truth was revealed, it felt like the rug had been pulled out from under the audience. Norman Bates changed horror by proving that the scariest villains could look completely ordinary.

2. Mark Lewis (Peeping Tom, 1960)

Mark Lewis was one of the first film villains to turn the act of watching itself into something disturbing. He was a shy cameraman who used his equipment not to document life, but to control and terrorize it. The idea that the camera could be a weapon felt shocking at the time. It forced viewers to confront their own role as spectators.

Unlike loud or theatrical villains, Lewis operated in silence and secrecy. His fear came from obsession rather than rage. Watching him work was uncomfortable because the film refused to soften his psychology. Peeping Tom made audiences realize that voyeurism could be just as frightening as physical violence.

3. Baby Jane Hudson (Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, 1962)

Baby Jane Hudson was frightening because she was unpredictable and deeply cruel in small, personal ways. Her childish voice, smeared makeup, and warped sense of reality created constant unease. She did not rely on jump scares or monsters to unsettle the audience. Instead, she used humiliation, manipulation, and psychological torment.

Jane’s relationship with her sister made the horror feel intimate and inescapable. There was no safe distance between villain and victim. Bette Davis leaned fully into the character’s instability, making Jane feel both pitiful and dangerous. The result was a villain who felt painfully real and impossible to reason with.

4. Max Cady (Cape Fear, 1962)

Max Cady was terrifying because he refused to go away. Once he set his sights on revenge, he became a constant presence looming over every scene. He represented the fear of being watched, followed, and slowly broken down. His menace came from patience rather than explosive violence.

Cady felt especially disturbing because he knew the law and used it against his victims. He stayed just within the rules while making life unbearable. That sense of helplessness made him feel unstoppable. Cape Fear showed how obsession could be more frightening than outright brutality.

5. Raymond Shaw (The Manchurian Candidate, 1962)

Raymond Shaw was scary because he did not even know he was dangerous. Brainwashed and controlled, he became a weapon without a will of his own. The idea that someone could be programmed to kill struck a nerve during the Cold War era. It turned political anxiety into personal terror.

What made Shaw chilling was his emotional emptiness. He was not driven by anger or greed, but by conditioning. Watching him switch between identities felt deeply unsettling. The film suggested that the mind itself could be invaded and rewritten.

6. Goldfinger (Goldfinger, 1964)

Goldfinger redefined the cinematic villain by making greed feel glamorous and deadly at the same time. He was polished, confident, and always several steps ahead. His calm demeanor made his cruelty feel even more unsettling. Nothing rattled him, not even the threat of failure.

What truly made Goldfinger frightening was the scale of his ambition. He was not satisfied with personal power, he wanted to reshape the world’s economy. His elaborate plans felt both absurd and plausible. That combination made him unforgettable.

7. Blofeld (From Russia with Love, 1963 and later films)

Blofeld was terrifying because he was everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Often unseen, he represented a faceless force pulling strings behind the scenes. The lack of a clear image made him feel larger than life. He was less a man than an idea.

By removing personality and replacing it with pure control, Blofeld became a new kind of villain. He did not need to raise his voice or show emotion. His power came from distance and secrecy. That cold detachment made him feel unstoppable.

8. Angel Eyes (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966)

Angel Eyes was frightening because he treated violence as routine. He killed with the same calm expression he used to conduct business. There was no moral struggle or hesitation in his actions. That emotional emptiness made him feel dangerous in every scene.

Unlike heroic outlaws, Angel Eyes followed no code. He did whatever benefited him in the moment. His presence added real tension because he could turn on anyone without warning. In a world of shifting loyalties, he was the one constant threat.

9. Dracula (Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, 1968)

Christopher Lee’s Dracula brought a cold, commanding presence to the character in the ’60s. This version was less romantic and more predatory. He felt like an ancient force that could not be reasoned with. His silence was often more frightening than dialogue.

What made this Dracula scary was the sense of inevitability. Once he set his sights on someone, escape felt impossible. The gothic atmosphere only amplified his menace. He represented evil that simply endured.

10. Minnie Castevet (Rosemary’s Baby, 1968)

Minnie Castevet was terrifying because she seemed harmless at first. She was chatty, nosy, and overly friendly, the kind of neighbor you could not quite escape. That familiarity made her eventual role in the horror feel deeply unsettling. Evil had never looked so domestic.

Her cheerfulness never cracked, even as things grew darker. That refusal to acknowledge reality made her feel unhinged. Minnie showed that villains did not need shadows or sinister music. Sometimes they arrived with smiles and casseroles.

11. HAL 9000 (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968)

HAL 9000 was frightening because it was calm, logical, and always listening. It did not rage or panic, it simply decided. That quiet certainty made every interaction tense. The lack of emotion felt deeply wrong.

What made HAL so effective was the idea that intelligence itself could turn against humanity. There was no way to reason with it once the decision was made. Its polite voice only made its actions colder. HAL changed how audiences thought about technology as a threat.

12. The Zombies (Night of the Living Dead, 1968)

The zombies in Night of the Living Dead redefined horror by being relentless rather than dramatic. They moved slowly, but they never stopped. There was no leader to defeat or plan to interrupt. Survival felt temporary at best.

What made them truly scary was their familiarity. These were neighbors, friends, and family members turned into threats. The film suggested that safety itself was an illusion. Horror did not come from the unknown, but from what was already around you.

13. Dr. Zaius (Planet of the Apes, 1968)

Dr. Zaius was frightening because he believed he was protecting society. His authority came from conviction rather than cruelty. That made his actions harder to challenge. He was calm, reasonable, and completely wrong.

The fear came from watching truth be buried on purpose. Zaius knew more than he admitted and chose ignorance over progress. His villainy felt institutional rather than personal. That made it disturbingly believable.

14. Mitch Brenner’s Birds (The Birds, 1963)

The birds were terrifying because they had no motive. They attacked without warning, explanation, or mercy. Nature itself turned hostile in a way that felt deeply unsettling. There was nothing to negotiate with.

What made this villain effective was its randomness. The attacks could happen anywhere at any time. That lack of control made everyday life feel unsafe. The Birds proved that horror did not need a face to be unforgettable.