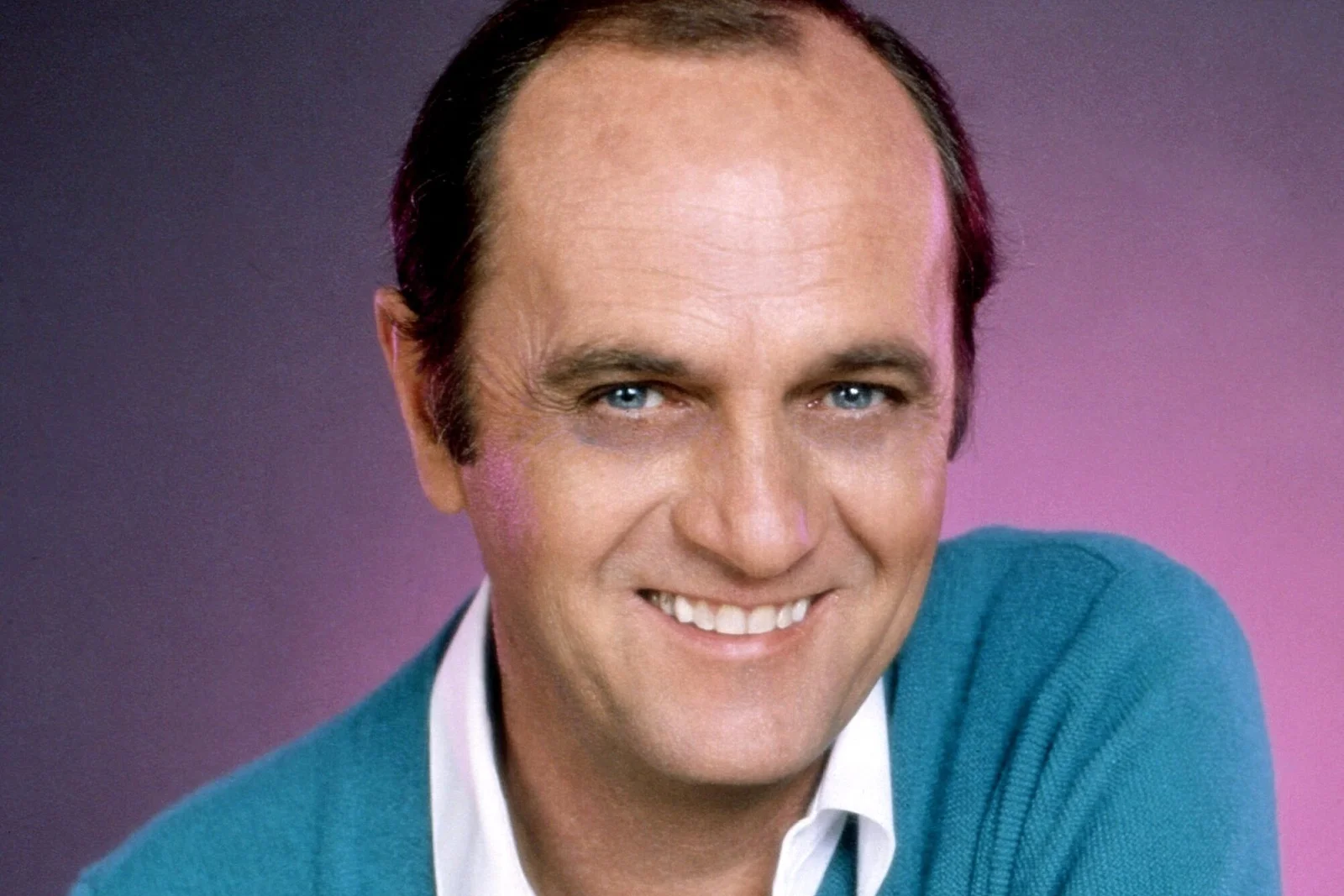

In a comedy landscape often dominated by broad gestures and loud personalities, Bob Newhart carved out his own distinctive niche with a deliberately quiet, stammering style that somehow made everyday observations explosively funny. His deadpan delivery, perfectly timed pauses, and subtle reactions could accomplish more with a raised eyebrow than most comedians achieve with elaborate setups. Newhart’s genius lay in his ability to remain the calm center of increasingly absurd situations, playing the bewildered everyman trying to maintain his dignity while the world around him descended into madness. From his groundbreaking comedy albums to his iconic television series, Newhart’s understated approach to humor has proven remarkably durable, influencing generations of comedians while still drawing laughs decades later.

1. The Driving Instructor Telephone Routine

Perhaps no single routine better exemplifies Newhart’s genius than his one-sided telephone conversation as a driving instructor dealing with his most challenging student yet. The beauty of this bit lies in what’s left unsaid—the audience only hears Newhart’s increasingly desperate attempts to guide his unseen student through basic driving maneuvers, with each calm instruction followed by growing alarm as catastrophe apparently unfolds on the other end of the line. His progression from professional patience to barely concealed panic creates a mental picture far funnier than any visual could have achieved. So extensive was Newhart’s legacy, The Kennedy Center paid him special tribute for his work in theater and as a citizen serving his country.

What makes this routine truly masterful is Newhart’s commitment to believability throughout—his character genuinely wants to help this student succeed despite mounting evidence that everyone would be safer if they remained permanently off the road. Even as the situation escalates to absurd proportions, Newhart never breaks character or acknowledges the comedy, making his flustered reactions and desperate improvisations all the more hilarious. The routine’s perfect pacing—starting with minor difficulties that snowball into chaos—demonstrates Newhart’s architectural approach to comedy, building a structure where each laugh sets up a bigger one to follow.

2. The Button-Down Mind Album’s Instant Success

When Newhart’s debut comedy album “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart” was released in 1960, no one—least of all the former accountant himself—expected it would become the first comedy album to hit #1 on the Billboard charts, outselling Elvis Presley and the Sound of Music soundtrack. The album’s unprecedented success represented a seismic shift in American comedy, proving that intelligent, low-key observational humor could connect with mainstream audiences accustomed to broader comedic styles. The sight of this unassuming everyman accepting the Album of the Year Grammy (beating Frank Sinatra, among others) perfectly captured the delightful improbability of his sudden rise. AllMusic dives into the nuances of Newhart’s work immortalized in album form.

What made this triumph particularly satisfying was that Newhart had abandoned his accounting career after recording himself performing fake telephone calls to entertain friends—a hobby that unexpectedly launched one of comedy’s most distinguished careers. His success validated a completely different approach to comedy that valued intelligence and subtlety over catchphrases and physical humor. The album’s title itself—”The Button-Down Mind”—perfectly captured Newhart’s persona: seemingly conventional and restrained on the surface, but harboring wonderfully subversive and absurdist thoughts just beneath that professional exterior.

3. The Sir Walter Raleigh Phone Call

Among Newhart’s most beloved routines is his imagined telephone conversation between a marketing executive and Sir Walter Raleigh, who’s trying to explain his new discovery—tobacco—to a skeptical listener. The executive’s increasingly baffled reactions as he tries to understand why anyone would want to set dried leaves on fire and inhale the smoke creates a masterclass in comedic escalation. Newhart’s performance makes the routine feel like we’re eavesdropping on history’s most disastrous product pitch meeting, with each new detail about tobacco making the concept sound more ridiculous. IndieWire further lists cinematic works that show off Newhart at this best.

The routine’s genius lies in its anachronistic perspective—applying modern marketing logic to historical innovation creates a delicious cognitive dissonance. Newhart’s character tries valiantly to remain professional while struggling to comprehend why anyone would buy this bizarre product, his corporate politeness barely masking his growing conviction that Sir Walter has completely lost his mind. The routine culminates with the executive trying to gently dissuade Raleigh from mentioning his other discovery—”You’ve what? You’ve dipped some leaves in water? Tea? You call it tea? T-E-A? No, that’ll never catch on either.”

4. The Psychology of Bob Hartley

Newhart’s portrayal of Chicago psychologist Dr. Bob Hartley on “The Bob Newhart Show” created one of television’s most subtly funny characters—a man whose professional life involved helping others navigate their neuroses while being hilariously blind to his own quirks and anxieties. The comedic tension between Hartley’s role as a mental health professional and his personal awkwardness created endless opportunities for Newhart’s trademark reactions. His sessions with his therapy group showcased Newhart’s brilliant ensemble timing, allowing him to function as both straight man and comedic foil depending on the moment.

What made Bob Hartley particularly endearing was his genuine desire to help others despite his own imperfections, creating a character who was simultaneously an authority figure and an everyman struggling with ordinary problems. His relationship with his wife Emily (brilliantly played by Suzanne Pleshette) featured some of television’s most realistic and funny married couple dynamics—affectionate but unsparing, supportive yet exasperated. The show’s workplace setting also allowed Newhart to develop his specialty: reacting to increasingly bizarre statements from others with a mixture of confusion, forced politeness, and mounting disbelief that perfectly mirrored the audience’s own reactions.

5. The Newhart Series Finale

Television history contains few moments as unexpectedly hilarious as the final scene of Newhart’s second successful sitcom, “Newhart,” which ran from 1982 to 1990. After eight seasons of playing Vermont innkeeper Dick Loudon surrounded by increasingly eccentric townspeople, the series conclusion delivered the ultimate punchline: Newhart wakes up in bed—not as Dick Loudon but as Dr. Bob Hartley from his previous series, next to his wife Emily from “The Bob Newhart Show.” He then describes his bizarre dream about running an inn in Vermont, effectively revealing that the entire eight-year “Newhart” series had been Bob Hartley’s dream.

This meta-joke worked on multiple levels—it playfully acknowledged Newhart’s television history, subverted the cliché of the “it was all a dream” ending by making it deliberately absurd, and reunited him with Suzanne Pleshette for a perfect callback to their beloved chemistry. The audience’s shocked reaction when Pleshette appeared—they hadn’t been told about this twist—created a moment of genuine surprise rarely achieved in television comedy. Most impressively, this clever conceit has only grown in stature over time, regularly appearing on lists of the greatest television finales ever produced, proving that Newhart’s understated approach could still deliver spectacularly unexpected comedy.

6. The Empire State Building Jumper Routine

Among Newhart’s most darkly brilliant routines was his telephone conversation as a police officer trying to talk down a potential jumper from the Empire State Building. The routine demonstrated Newhart’s willingness to find humor in uncomfortable situations without ever seeming cruel or exploitative. His character begins with textbook crisis intervention techniques before gradually revealing his complete unsuitability for this sensitive task—getting distracted by bureaucratic concerns about jurisdiction, paperwork requirements, and whether the jumper has the proper permits for his planned activity.

What elevates this routine beyond mere dark humor is Newhart’s portrayal of a fundamentally decent person who genuinely wants to help but is hopelessly constrained by procedural thinking and institutional limitations. The comedy emerges from his character’s inability to transcend his training rather than from any callousness toward the jumper’s plight. As the conversation progresses and the officer becomes increasingly invested in preventing the jump—partly out of compassion but also to avoid dealing with the administrative headache it would cause—we witness a perfect example of Newhart finding humor in the gap between institutional responses and human needs.

7. The Submarine Commander Routine

Newhart’s ability to find comedy in crisis management reached its apex in his submarine commander routine, where he portrays a naval officer dealing with the increasingly problematic maiden voyage of a new submarine. Beginning with minor concerns (“The radio doesn’t work? Well, that’s why we have these test runs”), his character maintains an admirably calm demeanor while the situation deteriorates to surreal proportions, culminating with the revelation that the submarine may have been launched without a door—a design oversight of considerable significance.

The genius of this routine lies in Newhart’s escalating attempts to maintain protocol and leadership dignity in the face of mounting absurdity. His commander tries valiantly to view each catastrophic report as merely an interesting data point rather than cause for panic, attempting to reassure his increasingly alarmed crew with hilariously inadequate corporate-speak and management platitudes. The routine perfectly captures the comedy of organizational dysfunction—the submarine becomes a metaphor for any institution where authority figures must pretend to have answers when they’re clearly in over their heads.

8. The Grace Under Pressure of Dick Loudon

In “Newhart,” his portrayal of Dick Loudon—a successful how-to book author who purchases a Vermont inn—allowed Newhart to perfect his signature comedic dynamic: the sane man surrounded by eccentrics. As the only normal person in a town populated by increasingly bizarre characters, Dick’s reactions of bewilderment, frustration, and resigned accommodation provided the perfect showcase for Newhart’s reactionary comedy. His attempts to apply logical thinking to his neighbors’ decidedly illogical behavior created a comic tension that sustained the series through eight successful seasons.

The character’s evolution over the series reflected a wonderfully realistic arc—initially shocked by the town’s eccentricities, eventually learning to anticipate them, and finally developing strategies to navigate them without completely sacrificing his own sanity. His relationship with his wife Joanna (Mary Frann) created a small island of normality amid the chaos, with their shared glances and shorthand communication reflecting a couple united in their bewilderment at their adopted community. The show’s supporting characters—particularly the backwoodsmen Larry, Darryl, and Darryl—became increasingly outlandish, allowing Newhart’s understated reactions to grow correspondingly more effective.

9. The Abraham Lincoln Press Secretary Routine

One of Newhart’s most brilliant conceptual pieces imagined a press secretary trying to coach Abraham Lincoln on the upcoming Gettysburg Address, offering increasingly desperate suggestions to make his remarks more media-friendly. The comedy emerges from the collision between Lincoln’s historical gravitas and the shallow concerns of modern public relations, with Newhart’s character focusing on presentation details while completely missing the profound content of Lincoln’s address. His suggestions to “jazz it up” with audience participation or catchier phrasing highlights the contrast between historical substance and contemporary style.

The routine works as both historical comedy and media satire, imagining how modern communication techniques might have undermined one of American history’s most profound moments. Newhart’s press secretary character becomes increasingly frustrated with Lincoln’s insistence on using phrases like “four score and seven years ago” instead of simply saying “87 years ago,” creating a perfect clash between historical eloquence and modern directness. By the routine’s end, we hear the beleaguered press secretary attempting to convince Lincoln that nobody remembers speeches anyway—a punchline whose irony gives the comedy an additional historical resonance.

10. The Bus Driver’s School Routine

Newhart’s routine about the first day of training at a bus driver’s school showcases his ability to find absurdity in seemingly straightforward instructional situations. As the instructor moves through increasingly bizarre scenarios that drivers might encounter—from mundane fare disputes to truly outlandish passenger behaviors—his matter-of-fact delivery suggests these are all routine challenges that any professional driver should expect to handle with aplomb. The comedy builds as the situations become more surreal while the instructor’s tone remains consistently practical and unalarmed.

What makes this routine particularly effective is how it mirrors actual training sessions we’ve all experienced, where instructors often seem to downplay genuinely challenging situations or present complex problems as if they have simple solutions. Newhart’s instructor character maintains his authoritative demeanor even while describing scenarios that would clearly be beyond any reasonable job expectation, creating a perfect satire of professional training’s limitations. The routine culminates with advice on handling a passenger who wants to commit suicide by jumping off the moving bus—”Try to talk them out of it, but remember, we do have a schedule to maintain.”

11. The Retirement Home Dinner Scene

One of “The Bob Newhart Show’s” most memorable moments occurs when Bob and Emily have dinner with his parents at their retirement community, resulting in a meal of hilariously slow progression as the elderly servers and residents operate at a pace that tests Bob’s patience to its breaking point. Newhart’s mounting frustration—expressed primarily through subtle facial expressions rather than outbursts—creates a masterclass in reactive comedy as he attempts to maintain politeness while silently calculating whether they’ll finish dinner before breakfast service begins.

The scene works brilliantly because it captures a universal experience—the adjustment to different tempos in different environments—without mockery or cruelty toward the elderly characters. Bob’s frustration stems not from lack of compassion but from his own inability to adjust to a different rhythm of life, making him the butt of the joke rather than the retirement community residents. His attempts to subtly speed things along without seeming rude create a perfect showcase for Newhart’s physical comedy skills, proving he could generate enormous laughs with the smallest gestures and expressions.

12. The Tobacco Industry Spokesman Routine

Decades before the major tobacco settlements, Newhart created a devastatingly funny routine featuring a tobacco industry public relations man attempting to respond to the first scientific studies linking smoking with health problems. The spokesman starts with confident denial before moving through increasingly desperate rhetorical strategies as the evidence becomes harder to dismiss. His progression from “These studies are inconclusive” to suggesting that correlation doesn’t imply causation to finally proposing that cancer might actually cause smoking rather than vice versa creates a perfect satire of corporate obfuscation.

What makes this routine particularly impressive is how it tackles a serious public health issue while keeping the focus on institutional dishonesty rather than individual smokers. Newhart’s spokesman character isn’t portrayed as evil but as someone trapped in an impossible job—defending the indefensible with whatever rhetorical tools he can grasp. The comedy emerges from watching this process of rationalization unfold in real time, with each new spin attempt becoming more transparent than the last. The routine demonstrated Newhart’s ability to create sharp social commentary while maintaining his characteristic light touch.

13. The Introduction of Darryl and Darryl

Few television moments captured the essence of Newhart’s comedic style better than the introduction of the silent brothers Darryl in the “Newhart” series. When local woodsman Larry first introduces his brothers, both named Darryl, Dick Loudon naturally asks which is which, creating a perfect setup for Larry’s deadpan response: “That doesn’t really matter.” What elevated this from a simple joke to comedy legend was the brothers’ complete silence—they never spoke a single word throughout the series (until the finale), allowing Newhart countless opportunities to react to their mute presence.

The brilliance of this running gag was its simplicity and sustainability—the writers found endless ways to incorporate the silent brothers into scenarios where their lack of speech created maximum awkwardness for Dick. Newhart’s increasing familiarity with their peculiarity created a wonderful character arc—his initial bewilderment gradually evolving into resigned acceptance. The studio audience’s anticipatory reaction whenever the brothers appeared demonstrated how effectively this minimalist comedy concept had connected with viewers. When the brothers finally did speak in the series finale (both simultaneously saying “QUIET!” after eight years of silence), it provided one of television’s most satisfying payoffs to a long-running joke.

Bob Newhart’s genius reminds us that in comedy, what’s not said can be as powerful as what is. His perfectly calibrated reactions, strategic pauses, and subtle double-takes created space for audiences to actively participate in the comedy rather than passively receive it. While louder, more aggressive comic styles might seem more immediately impressive, Newhart’s understated approach has demonstrated remarkable staying power—his routines remain fresh and funny decades after their creation because they tap into universal human experiences of confusion, frustration, and the attempt to maintain dignity amid life’s absurdities. In a cultural landscape that often equates volume with impact, Newhart’s quiet mastery proves that sometimes the biggest laughs come from the smallest reactions.