Before screens dominated our attention and virtual worlds became our playgrounds, an entire generation discovered the wonders of nature through a handful of beloved figures who brought the outdoors into our living rooms. These charismatic guides—some human, some animated, all memorable—sparked curiosity about the natural world in ways that shaped our relationship with the environment for decades to come. For Baby Boomers who grew up in the golden age of nature programming and outdoor adventures, these twelve icons didn’t just entertain; they fostered a deep connection with wildlife, conservation, and the call of the wild that many still feel today. From trusted television hosts to illustrated forest guardians, these were the friendly faces that made us want to step outside and explore.

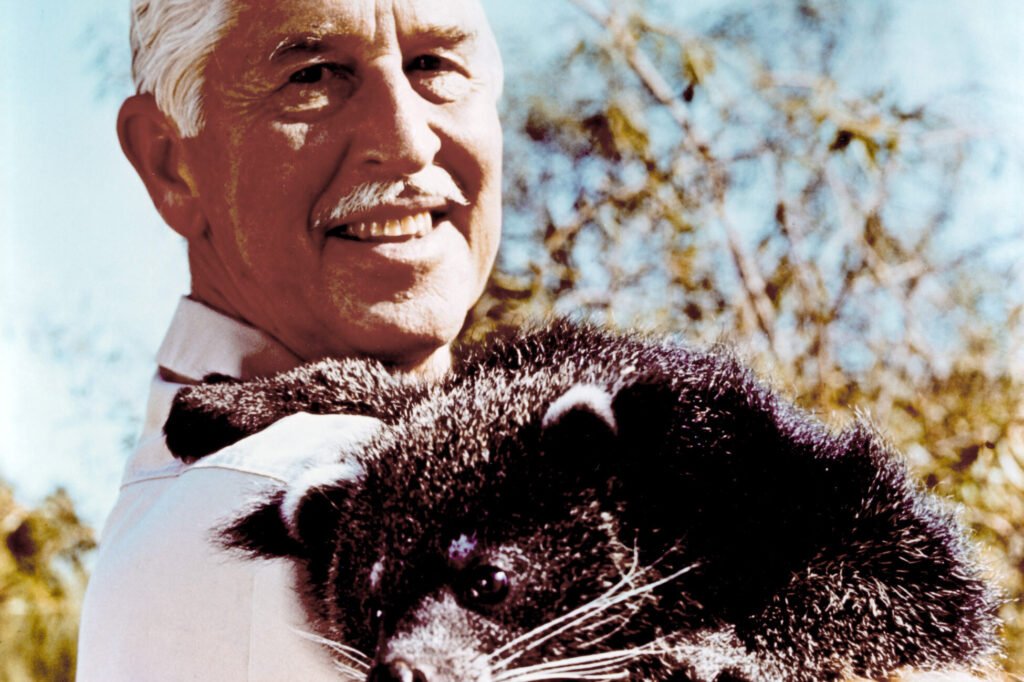

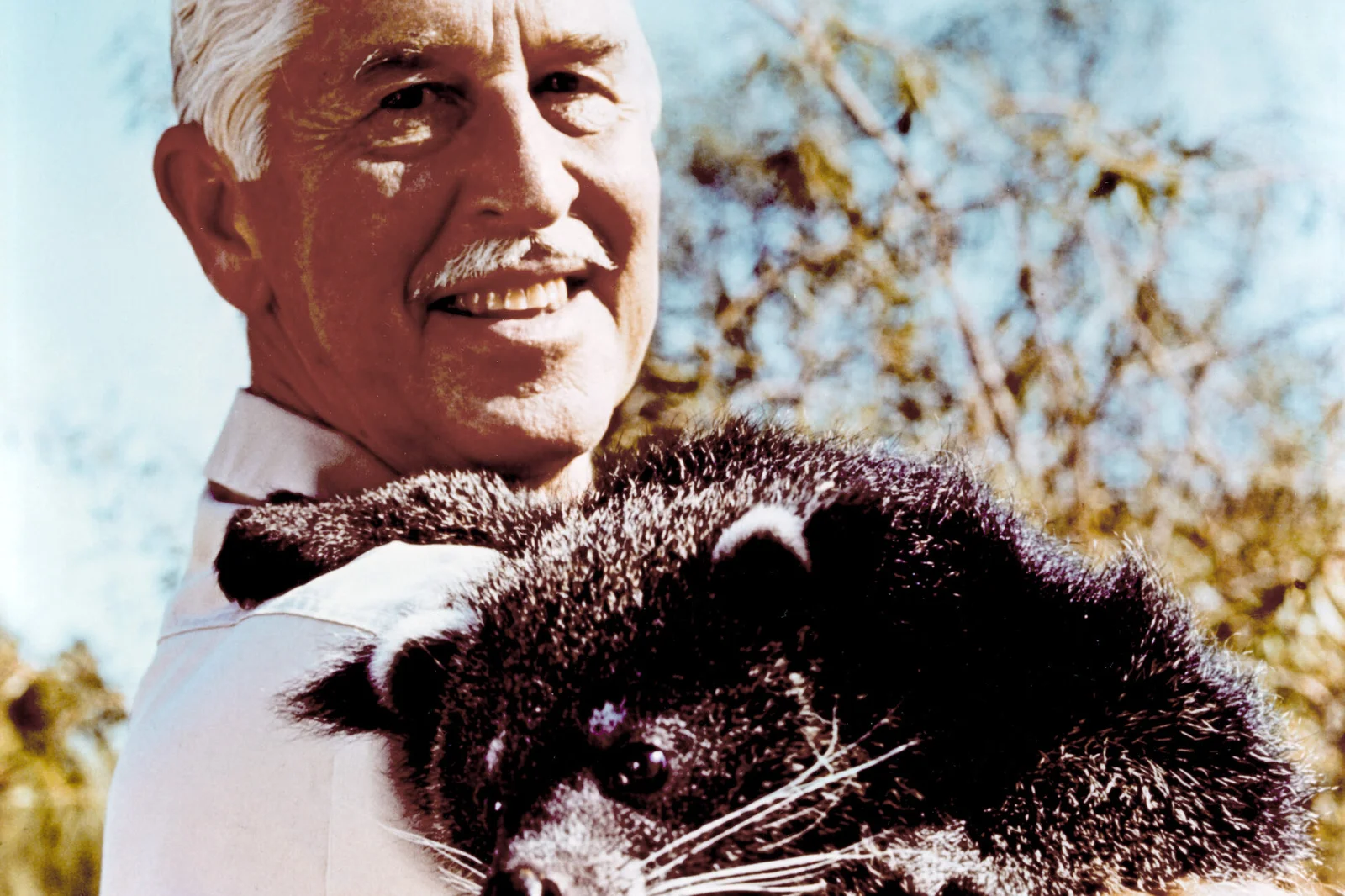

1. Marlin Perkins and “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom”

Sunday evenings from 1963 to 1985 found families gathered around television sets as silver-haired Marlin Perkins introduced Americans to exotic wildlife from the comfort of their living rooms. The dignified zoologist narrated adventures while his younger sidekick Jim Fowler did the dangerous work—wrestling anacondas or tagging bears—prompting the running family joke: “I’ll stay here while Jim checks if that lion has dental problems.” Perkins had a remarkable ability to make educational content genuinely exciting, though children quickly noticed how his narration would seamlessly transition from charging rhinos to insurance policies, creating perhaps the earliest recognition of sponsored content among young viewers. To this day, Mutual of Omaha acknowledges and celebrates Marlin’s one-of-a-kind legacy.

What made Perkins truly special wasn’t just the exotic animals but his genuine respect for wildlife at a time when conservation wasn’t yet mainstream. His calm, authoritative voice described animal behavior with the perfect balance of scientific accuracy and accessible storytelling that made children feel like junior zoologists. Each episode created a generation of youngsters who begged for trips to the zoo, collected National Geographic magazines, and developed early conservation awareness—even if they also giggled whenever Perkins remained in the jeep while sending Jim into potential danger, a division of labor that became the show’s unintentional comedy signature.

2. Smokey Bear

“Only YOU can prevent forest fires” became imprinted on the collective consciousness of American children through the gentle but firm ursine spokesman in the ranger hat. Created in 1944 but reaching peak cultural influence through the 1950s and ’60s, Smokey Bear taught fire safety with a gravity that children instinctively respected—perhaps because his origin story involved a real bear cub rescued from a New Mexico wildfire. The anthropomorphized bear appeared on posters in schools, campgrounds, and forest visitor centers, his soulful eyes making children feel personally responsible for preventing wilderness disasters through careful management of campfires and matches. Forest History Society shines a light on just how extensive this creature’s impact has been and is to to date.

The character’s effectiveness stemmed from his perfect balance of authority and approachability—serious enough that children listened but friendly enough that they embraced his message rather than rebelling against it. Smokey became so influential that many Boomers still experience a twinge of guilt when lighting a barbecue without proper clearance or watching a campfire spark unexpectedly. His image evolved from stern forest protector to kindly conservation teacher as environmental awareness grew, but his core message remained consistent: nature needs human stewardship, and even the youngest citizens have a role to play in protecting America’s wilderness.

3. Jacques Cousteau and “The Undersea World”

With his distinctive red cap, French accent, and the research vessel Calypso, Jacques Cousteau transported landlocked Americans to underwater worlds previously inaccessible to ordinary viewers. His groundbreaking television specials throughout the 1960s and ’70s revealed the mysterious ocean depths with technological innovations like underwater cameras and breathing apparatus that he helped develop himself. Cousteau’s poetic narration describing marine life—delivered in his mesmerizing accent—transformed scientific documentation into something approaching art, making millions of children eager to explore tide pools and dream of becoming marine biologists. According to Barron’s, today, his descendants are determined to continue his noble work.

What distinguished Cousteau from other nature presenters was his evolution from explorer to environmentalist, bringing viewers along on his personal journey toward conservation awareness. Early episodes showcased adventure and discovery, while later programs increasingly emphasized ocean preservation and the impacts of pollution—a progression that mirrored society’s growing environmental consciousness. For many Boomers, Cousteau provided first exposure to environmental concepts that would later become central to public discourse, making children feel connected to distant coral reefs and responsible for their protection long before globalization made such connections commonplace.

4. Ranger Rick

The raccoon in ranger attire who appeared in the National Wildlife Federation’s children’s magazine became the trusted guide to backyard discoveries for millions of young nature enthusiasts. First published in 1967, Ranger Rick magazine featured the charismatic raccoon and his friends Deep Green Wood teaching conservation principles through illustrated adventures that made environmental stewardship feel like an exciting club rather than a classroom lesson. The magazine combined engaging wildlife stories with practical projects children could complete in their own neighborhoods—building bird feeders, identifying local insects, or creating backyard habitats.

What made Ranger Rick particularly effective was how he encouraged children to see nature as existing everywhere—not just in distant wilderness, but in suburban backyards and city parks. The magazine’s blend of entertainment and education extended children’s attention spans for environmental topics, with many households keeping issues for years as informal field guides. For countless Boomers, receiving the monthly magazine created not just environmental awareness but also reading habits that parents appreciated—making Ranger Rick one of the rare children’s subscriptions that satisfied both educational goals and entertainment desires simultaneously.

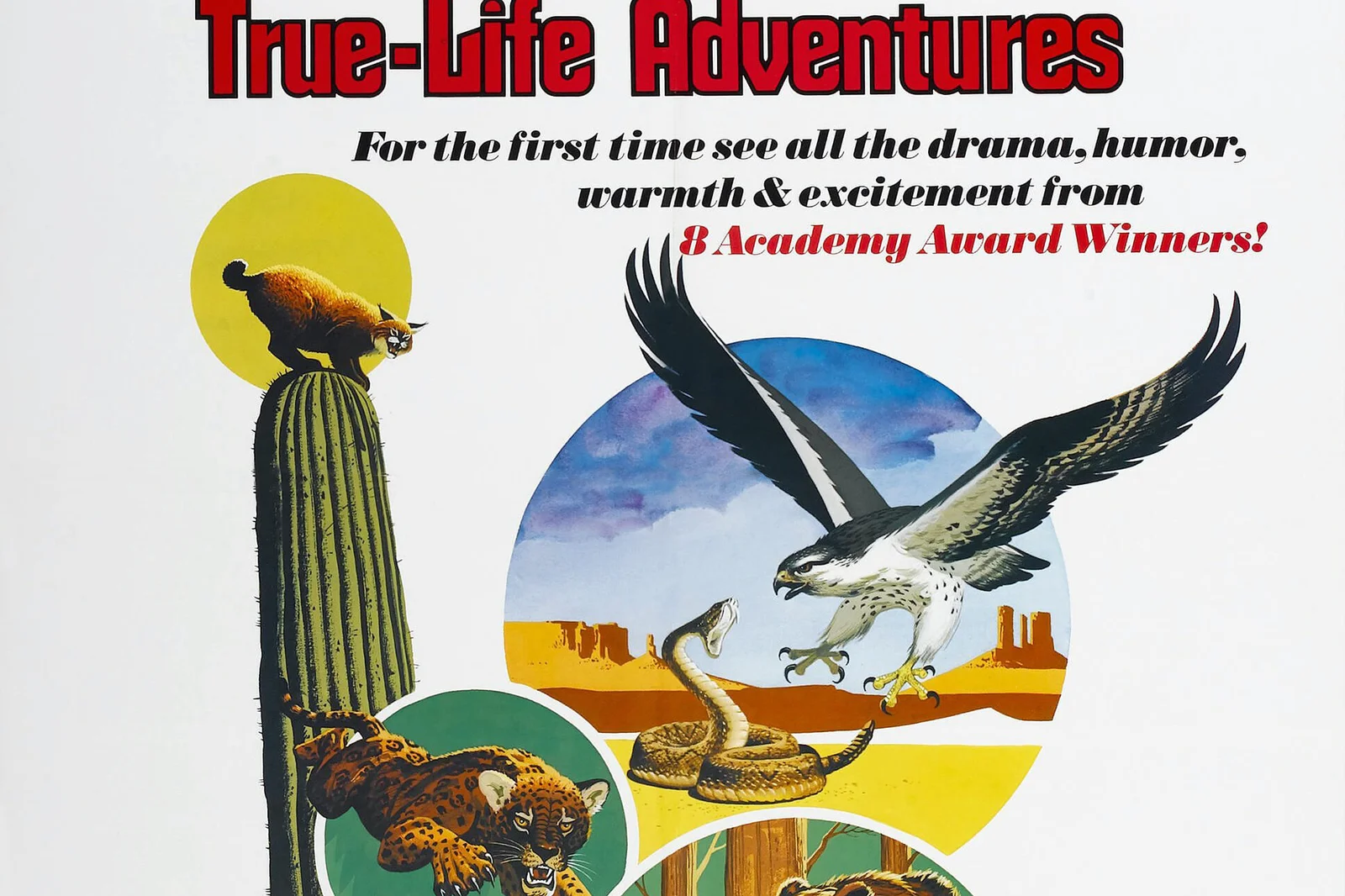

5. Walt Disney’s Nature Documentaries

Before Disney meant principally animation and theme parks, the studio produced groundbreaking “True-Life Adventures” nature documentaries that won eight Academy Awards between 1948 and 1960. These beautifully filmed wildlife features—with titles like “The Living Desert” and “The Vanishing Prairie”—introduced baby boomers to American wilderness with dramatic storytelling techniques that anthropomorphized animals just enough to create emotional investment without sacrificing scientific integrity. The familiar Disney production values elevated nature documentation to artistic heights, with musical scores that perfectly complemented animal behaviors and narration that found the perfect balance between education and entertainment.

What made these films particularly influential was their theatrical release—families experienced nature on the big screen as special events, often providing children’s first exposure to wildlife beyond dogs, cats, and occasional zoo visits. The dramatic cinematography captured behaviors rarely witnessed by human eyes—desert flowers blooming in time-lapse, predator-prey relationships unfolding in real time, birds performing elaborate mating rituals—creating indelible impressions that sparked lifelong interests in natural history. These films also represented early mainstream environmental awareness, with conservation messages subtly woven into narratives decades before environmentalism became a household concept.

6. Johnny Appleseed

The semi-mythological figure of Johnny Appleseed (based on nurseryman John Chapman) captured American children’s imagination through elementary school pageants, Disney’s animated short, and countless illustrated books. Portrayed as a gentle wanderer wearing a cooking pot as a hat and planting apple trees across the frontier, Johnny represented an accessible form of environmental stewardship that even the youngest children could understand and aspire to emulate. His simple message—that one person could transform the landscape through persistent, small actions—resonated deeply with children developing their sense of agency in the world.

The character’s blend of historical basis and folk embellishment made him particularly effective as an environmental icon—real enough to believe in but legendary enough to inspire. For many Boomers, Johnny Appleseed represented their first exposure to conservation concepts, teaching that planting trees was both practical (providing food) and virtuous (creating beauty and habitat). His character embodied values of simplicity, kindness to animals, and living harmoniously with nature that contrasted with the increasing materialism and technological focus of post-war America, offering a nostalgic but relevant environmental ethic that many still find appealing in our digital age.

7. Euell Gibbons and Grape-Nuts Commercials

“Ever eat a pine tree? Many parts are edible” became an unlikely catchphrase when wilderness survival expert Euell Gibbons appeared in Grape-Nuts cereal commercials in the early 1970s. The bearded outdoorsman who authored “Stalking the Wild Asparagus” brought foraging and wild food knowledge into mainstream awareness, making previously obscure naturalist skills suddenly fashionable. Gibbons represented a countercultural perspective that appealed to Vietnam-era youth seeking authenticity and self-sufficiency, while his grandfatherly appearance made these alternative ideas palatable to their parents’ generation.

What made Gibbons particularly influential was his timing—appearing as spokesman during the first Earth Day era when environmental consciousness was rising but practical skills were declining. His commercials and books suggested that nature wasn’t just for aesthetic appreciation but direct sustenance, a radical concept for suburban Americans increasingly disconnected from food sources. For many Boomers, Gibbons sparked curiosity about edible plants in their own neighborhoods, leading to family nature walks specifically seeking wild berries or recognizable herbs. His unexpected fame also spawned countless parodies and jokes, ensuring his message reached even those who wouldn’t normally engage with naturalist content.

8. Lassie in “Forest Rangers” Seasons

While most remember Lassie as a farm dog, the collie’s adventures from 1964-1970 featured her working with Forest Rangers, fighting wildfires, tracking poachers, and rescuing lost hikers. These episodes introduced millions of children to forestry services and conservation concepts through the perspective of a beloved animal character, creating emotional connection with wilderness protection. The show’s formula typically involved Lassie detecting environmental problems that humans had overlooked—pollution in streams, injured wildlife, or dangerous forest conditions—demonstrating an inherent harmony between animals and nature that humans needed to respect and protect.

What made these episodes particularly effective was how they combined exciting outdoor adventure with subtle environmental messages at a time when conservation was not yet politically polarized. Children absorbed principles of wilderness stewardship while being entertained by dramatic rescues and animal heroics. The Forest Ranger period coincided with significant national legislation like the Wilderness Act and Clean Air Act, introducing children to conservation ethics that would become increasingly prominent in American culture. For many Boomers, these episodes created a sense that forests were both magical places for adventure and valuable resources requiring protection—concepts that informed their later support for environmental initiatives.

9. Golden Guide Nature Books

The distinctive yellow spines of Golden Guide nature books occupied bookshelves in countless Baby Boomer households, providing accessible introduction to birds, trees, insects, rocks, and other natural subjects. These pocket-sized field guides featured illustrated identification pages with clear, concise text suitable for elementary school readers but accurate enough for adult beginners. The books’ durability and compact size made them perfect companions for actual outdoor exploration, transitioning children from passive nature appreciation to active investigation and discovery.

What made these guides particularly influential was their democratic approach to natural history—assuming anyone could become a knowledgeable naturalist through observation and documentation. The illustrations emphasized field markings and distinctive features that could be observed without specialized equipment, empowering children to make their own identifications rather than relying solely on adult expertise. For many Boomers, receiving a Golden Guide meant graduating to “serious” nature study, often launching collections that grew book by book as interests expanded from birds to wildflowers to astronomy. These guides normalized scientific observation as a recreational activity, creating citizen naturalists who developed species awareness long before biodiversity became a common term.

10. Woodsy Owl

“Give a hoot, don’t pollute!” became a national earworm when Woodsy Owl debuted in 1970 as the U.S. Forest Service’s anti-pollution mascot. The wide-eyed owl with his ranger hat and green bow tie represented a direct response to increasing litter and environmental degradation, targeting children as agents of change during the dawn of the environmental movement. Woodsy appeared in public service announcements, school materials, and at forest visitor centers, always delivering his message with a perfect blend of concern and encouragement that made children feel empowered rather than scolded.

What made Woodsy particularly effective was his specific, actionable focus—unlike broader environmental messages, his campaign centered on individual behaviors like proper trash disposal and mindful consumption that children could immediately implement. The character’s debut coincided with the first Earth Day and growing public awareness of environmental issues, making him both a product of and contributor to the mainstreaming of conservation values. For many Boomers, Woodsy represented their first engagement with environmental citizenship—the concept that everyday actions had ecological consequences and that even children had responsibilities toward natural spaces.

11. Flipper

The bottlenose dolphin star of the 1964-1967 television series introduced millions of children to marine conservation through entertaining underwater adventures with her human companions. Flipper’s intelligence, playfulness, and apparent moral compass—often saving humans or identifying wrongdoers—created powerful emotional connections with an ocean creature many viewers would never encounter in person. The show’s Florida setting showcased marine ecosystems when most nature programming focused on terrestrial environments, expanding children’s concept of wildlife beyond forest animals to include coral reefs, sea turtles, and coastal habitats.

What made Flipper particularly influential was how the show portrayed human-animal relationships as partnerships rather than ownership or exploitation, revolutionary for its time. The dolphin worked with humans but maintained agency and wildness, communicating through body language and distinctive vocalizations that children quickly learned to interpret. For many Boomers, Flipper created first awareness of marine mammals as intelligent beings worthy of protection, laying groundwork for later support of conservation legislation and shifting attitudes toward animals in captivity. The show’s underwater cinematography—groundbreaking for television—revealed submerged worlds with visual clarity that inspired countless children to learn swimming specifically to explore beneath the surface themselves.

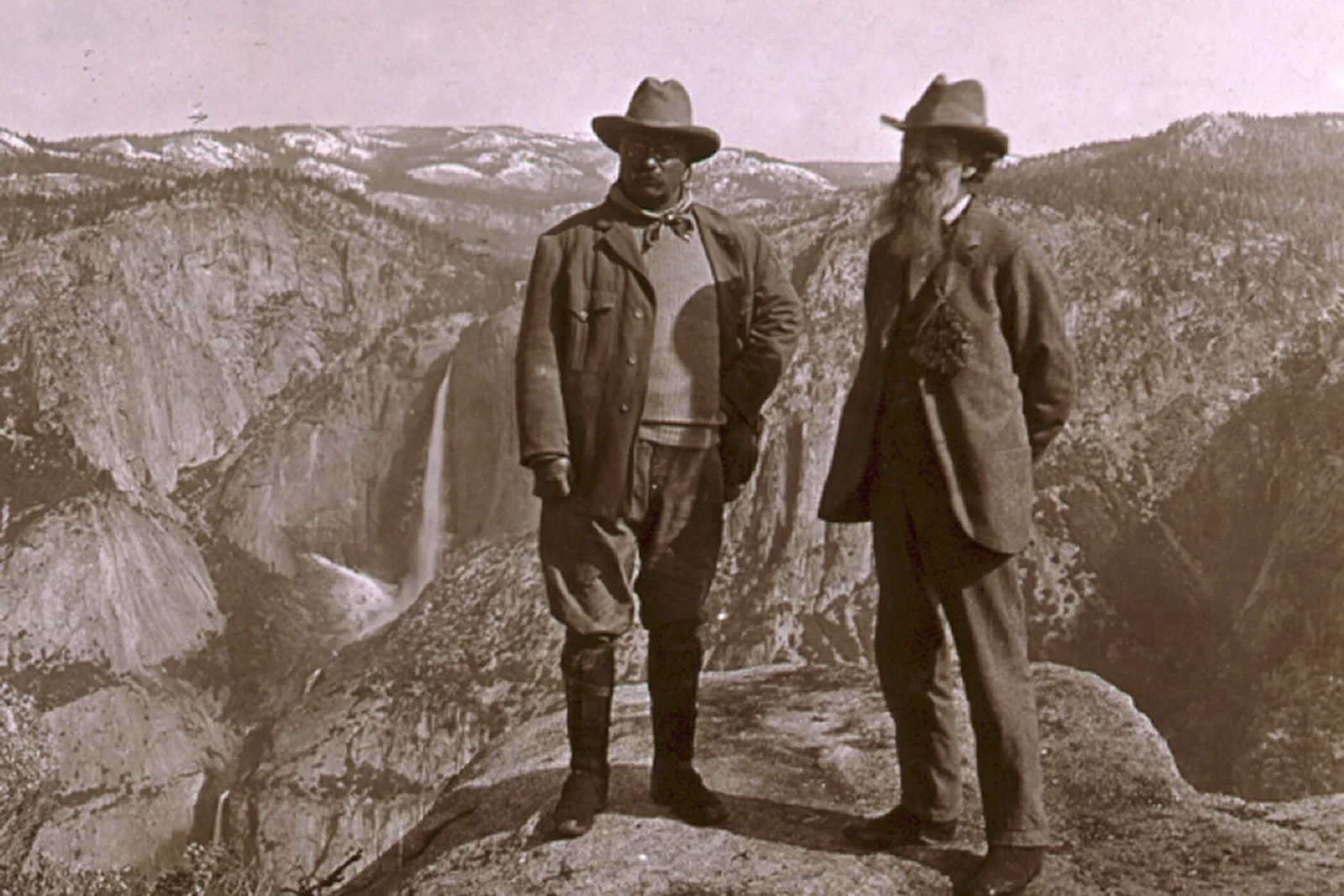

12. John Muir’s Legacy in School Curricula

While not a contemporary figure for Boomers, naturalist John Muir’s writings and philosophy became standard components of public education during the 1950s and ’60s, introducing millions of children to conservation principles through classroom exposure. Elementary school readers frequently included Muir’s accessible nature observations alongside basic information about his role establishing national parks and founding the Sierra Club. His quotations about wilderness preservation—”The mountains are calling and I must go” and “Going to the woods is going home”—became deeply ingrained in the American relationship with natural spaces.

What made Muir’s educational presence particularly influential was how it transcended geography—children in concrete urban environments encountered his wilderness ethic alongside those in rural settings, creating shared cultural touchpoints around nature appreciation. His writings presented conservation not as political policy but moral imperative, framing environmental protection within American values of heritage and responsibility to future generations. For many Boomers, Muir represented their first exposure to the concept that wilderness had intrinsic value beyond human use—a philosophical foundation that would inform environmental attitudes throughout their lives. His presence in curriculum also normalized the idea that spiritual connection with nature was compatible with scientific understanding, offering permission for emotional responses to natural beauty.

These twelve nature icons did more than entertain or educate—they shaped an entire generation’s relationship with the outdoors during formative years. Their influence extended beyond factual knowledge about wildlife or ecosystems to create emotional connections with natural processes and spaces. For Baby Boomers who grew up with these trusted guides, stepping outside meant entering a world they recognized from beloved books, programs, and characters who had taught them to see wonder in everything from backyard birds to distant wilderness. As this generation now watches grandchildren navigate nature primarily through screens, many feel renewed appreciation for these early influences that fostered direct, unmediated experiences with the natural world—experiences that research increasingly shows are essential for both environmental awareness and personal wellbeing.