Before DNA analysis, computer databases, and high-tech crime labs dominated detective shows, television sleuths relied on something far more entertaining—pure instinct and street smarts. The ’60s and ’70s gave us an unforgettable lineup of investigators who cracked cases through tenacity, psychological insight, and often unorthodox methods that would make today’s procedurally-correct detectives cringe. These characters didn’t need microscopes or algorithm matches; they had something more compelling: personality, intuition, and a knack for understanding human nature that kept viewers tuning in week after week.

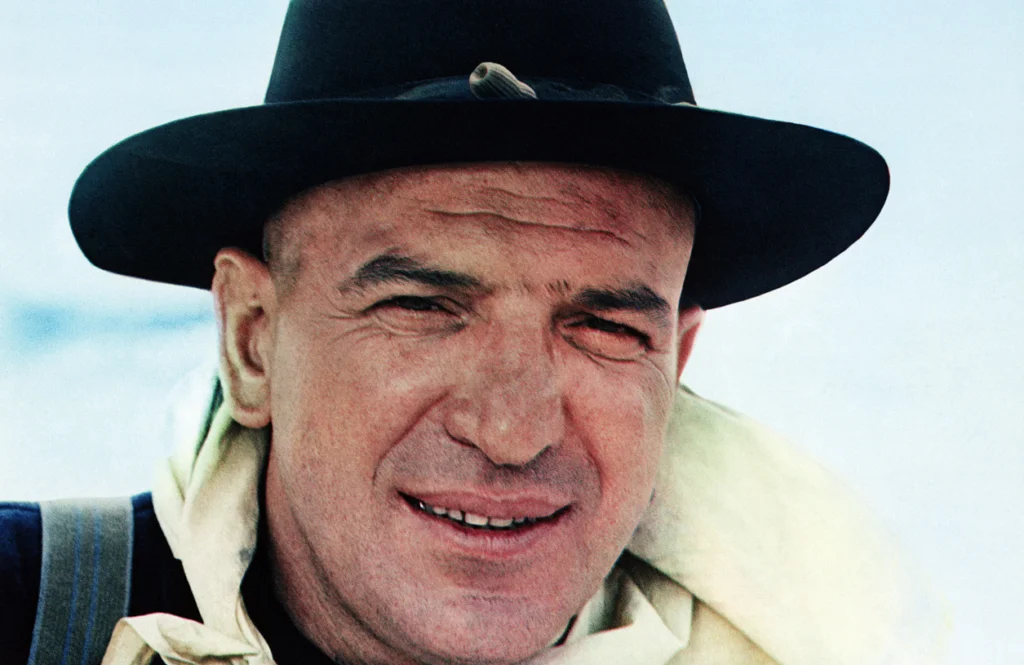

1. Columbo (Peter Falk)

Lieutenant Columbo redefined the detective genre by showing viewers the murderer’s identity in the opening scenes, transforming each episode from “whodunit” to “howcatchem” as the rumpled detective matched wits with typically wealthy, arrogant killers. With his wrinkled raincoat, ever-present cigar, and deceptively bumbling demeanor, Columbo lulled suspects into a false sense of security before skewering them with his famous phrase, “Just one more thing…” His apparent absentmindedness masked a brilliant analytical mind that caught the tiniest inconsistencies in suspects’ stories, proving that appearances could be devastatingly deceptive. So enduring does this show remain that BBC has reflected on why exactly the world still remembers this iconic detective.

Columbo never relied on forensic evidence, preferring instead to build psychological traps that exposed killers’ hubris and ultimately led them to incriminate themselves. His 1971-1978 series (later revived) showcased how a keen understanding of human vanity and arrogance was often more effective than any laboratory test. The lieutenant’s genius lay in his ability to notice subtle details—an out-of-place book, an illogical choice, a timeline that didn’t quite add up—and then slowly, methodically pursue those inconsistencies until the murderer’s carefully constructed alibi collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions.

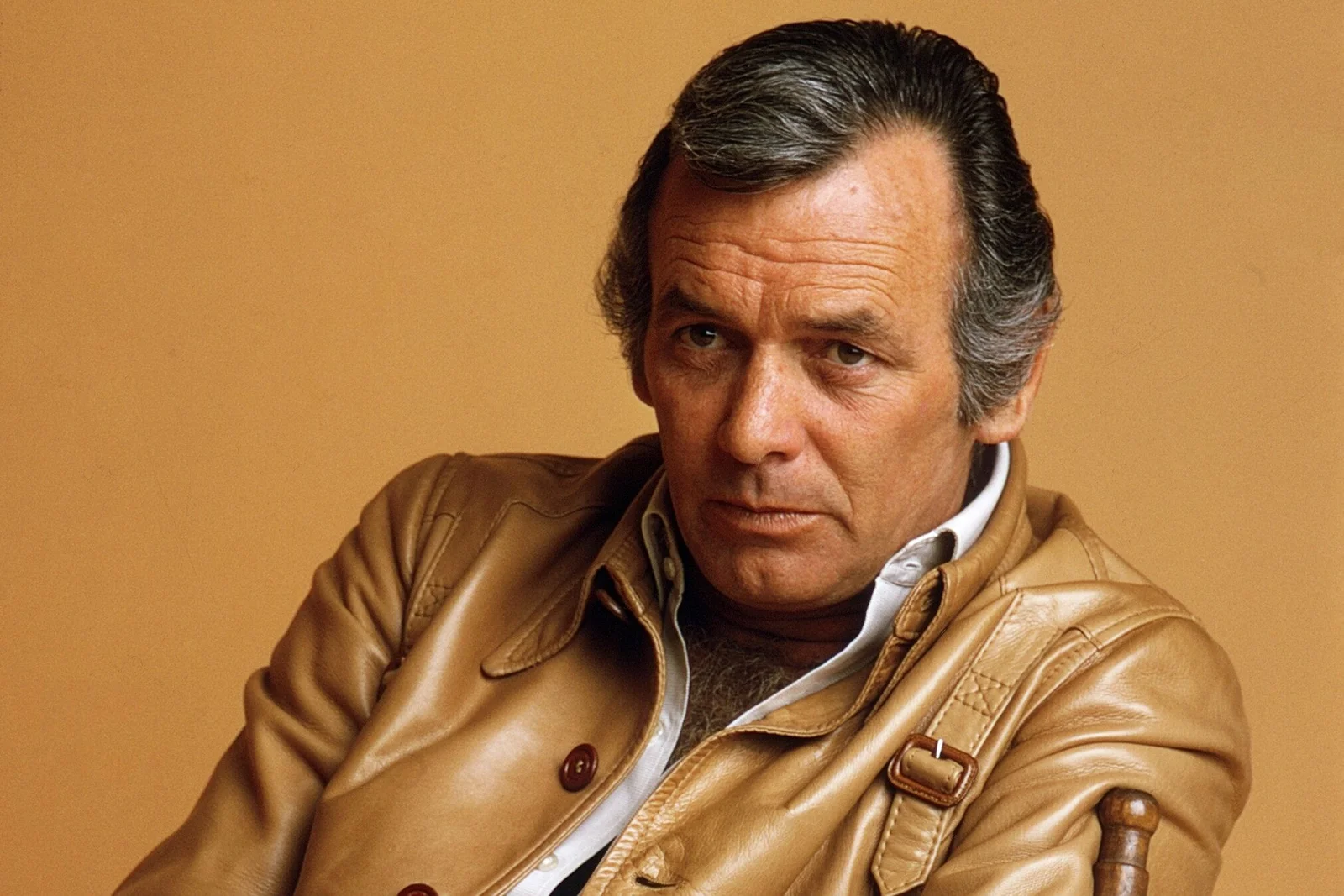

2. Jim Rockford (James Garner)

James Garner’s ex-con private investigator Jim Rockford lived in a ramshackle trailer on the beach, charged “$200 a day plus expenses,” and approached crime-solving with a world-weary pragmatism that resonated with post-Watergate America. Unlike the square-jawed heroic detectives that preceded him, Rockford preferred avoiding fistfights (though he inevitably ended up in them), maintained a healthy skepticism of authority, and often seemed more interested in getting paid than achieving justice. His investigations relied on an extensive network of street contacts, masterful telephone pretexting (creating false pretenses to obtain information), and a charming ability to talk his way into—and out of—dangerous situations. Yahoo has reviewed what happened to the cast who made this show so timeless.

“The Rockford Files” (1974-1980) featured a detective who solved cases through persistence rather than brilliance, often taking physical and emotional beatings along the way. Rockford’s investigative toolkit consisted of lock picks, business cards with changeable occupations, a Rolodex of dubious contacts, and an unparalleled ability to create convincing cover stories on the fly. His practical approach to detective work—follow the money, watch for the double-cross, and always check motives—showed viewers a gritty realism largely absent from earlier detective shows while establishing the template for countless flawed, reluctant investigators who would follow in later decades.

3. Kojak (Telly Savalas)

With his signature lollipop, gleaming bald head, and catchphrase “Who loves ya, baby?”, Lieutenant Theo Kojak brought a distinctive combination of tough-guy attitude and compassionate policing to 1970s detective drama. Working homicide in Manhattan’s gritty South Precinct, Kojak navigated a crime-ridden New York City through street smarts and psychological intimidation rather than scientific methods. His interrogation techniques relied on understanding criminals’ psychology and using their weaknesses against them—sometimes through sympathy, sometimes through fear, but always through a deeply intuitive grasp of human motivation. TVInsider took a leaf out of Kojak’s book and uncovered some additional secrets behind the series.

Kojak’s 1973-1978 series addressed social issues rare in earlier police dramas, including racism, drug addiction, and police corruption, giving his gut-instinct investigative approach a more contextual, sociological dimension. His crime-solving method centered on immersing himself in victims’ and suspects’ worlds, understanding the neighborhood dynamics and social forces that contributed to crime, and applying pressure at exactly the right moment to crack a case open. Kojak demonstrated that effective detective work wasn’t just about evidence but about understanding the human ecosystem where crimes occurred—a lesson that even today’s forensically-focused investigators would do well to remember.

4. Barnaby Jones (Buddy Ebsen)

After the murder of his son, retired private investigator Barnaby Jones returned to detective work, bringing old-school observation skills and gentle interrogation techniques to cases that younger, flashier detectives couldn’t crack. Portrayed by Buddy Ebsen (previously known as Jed Clampett on “The Beverly Hillbillies”), Jones upended expectations by solving complex crimes despite his advanced age and seemingly outdated methods. His unassuming, grandfatherly demeanor caused criminals to underestimate him—a fatal mistake as Jones’ lifetime of experience gave him insights into human behavior that more aggressive investigators often missed.

“Barnaby Jones” (1973-1980) showcased a detective who relied on patience, careful documentation, and the psychological advantage of being perpetually underestimated. Working with his daughter-in-law Betty (who handled the limited “technical” aspects of their investigations), Jones built cases through meticulous attention to detail and an almost supernatural ability to sense when suspects were lying. His approach to crime-solving reflected a belief that human nature hadn’t fundamentally changed despite societal upheaval, allowing him to apply decades of observational wisdom to the rapidly evolving cultural landscape of the 1970s.

5. Ironside (Raymond Burr)

Former San Francisco Police Chief Robert Ironside didn’t let paraplegia end his crime-fighting career, instead gathering a diverse team to be his “legs” as he solved cases from his wheelchair using pure intellect and psychological insight. Raymond Burr’s portrayal from 1967-1975 broke ground not just in representing disability on television but in showcasing a detective whose physical limitations enhanced rather than hindered his crime-solving abilities. Forced to rely entirely on observation, deduction, and understanding human psychology, Ironside developed investigative skills that put most able-bodied detectives to shame.

Ironside’s team—including Officer Ed Brown, juvenile delinquent-turned-assistant Mark Sanger, and socialite-turned-plainclothes-officer Eve Whitfield—executed his orders but relied on the Chief’s strategic direction and psychological profiling to guide investigations. His approach to solving crimes emphasized motive and opportunity over physical evidence, with Ironside often constructing elaborate scenarios based on understanding suspects’ psychological makeup rather than tangible clues. The series demonstrated that the most powerful investigative tool wasn’t found in a lab but in understanding the complex, often contradictory nature of human behavior and motivation.

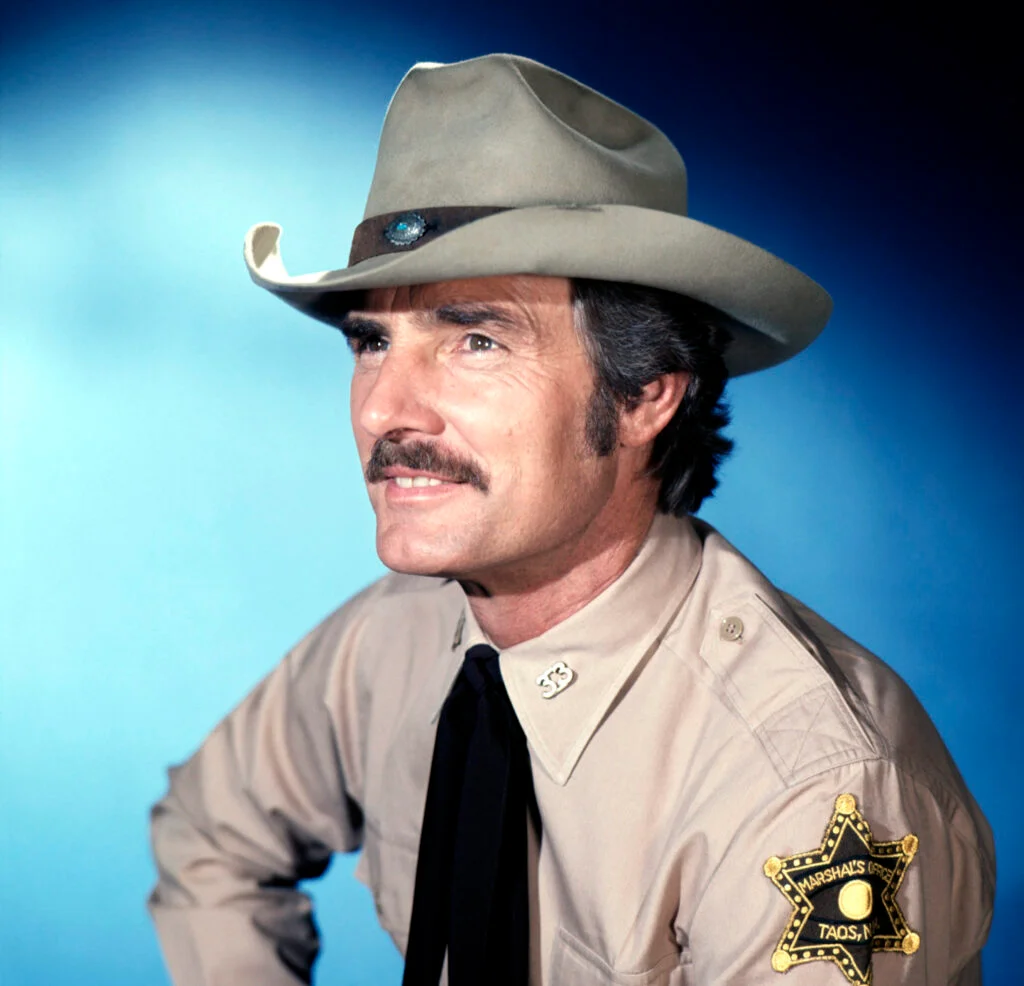

6. McCloud (Dennis Weaver)

“There you go!” became the catchphrase of Marshal Sam McCloud, a fish-out-of-water New Mexico lawman working “on loan” to the NYPD who brought rural common sense and cowboy ethics to sophisticated Manhattan crimes. Played with laconic charm by Dennis Weaver, McCloud rejected metropolitan police procedures in favor of intuition, horsemanship (yes, he occasionally rode horses through New York streets), and good old-fashioned straight talk. His Southwestern approach to crime-solving—direct questions, moral clarity, and an uncanny ability to see through urban deception—regularly outperformed the more procedurally-minded detectives around him.

During its 1970-1977 run, “McCloud” inverted the standard urban crime drama by suggesting that big-city sophistication often overcomplicated investigations that could be solved through straightforward reasoning and ethical clarity. McCloud’s investigative style relied on establishing genuine human connections across cultural divides, whether interviewing potential witnesses or interrogating suspects, proving that authentic engagement often yielded more information than technical procedures. His success demonstrated that understanding human nature transcended regional differences and that sometimes the most effective investigative approach was simply being genuine in a world of artifice and pretense.

7. Mannix (Mike Connors)

Joe Mannix took more physical punishment than perhaps any detective in television history, solving cases through a combination of persistence, toughness, and an almost superhuman ability to absorb beatings while continuing investigations. After leaving a high-tech detective agency in the first season (1967), Mannix established his own practice with the assistance of his secretary Peggy Fair, rejecting computer analysis in favor of legwork, informants, and when necessary, his fists. Mike Connors portrayed Mannix as a detective who literally couldn’t be deterred—no matter how many times he was knocked unconscious, shot, or thrown down stairs, he always returned to the case with renewed determination.

“Mannix” distinguished itself from other detective shows of the era by featuring genuinely brutal action sequences and a protagonist whose primary investigative technique was refusing to quit, even when physically outmatched or outnumbered. His relentless approach—showing up at locations until someone talked, following suspects until they made mistakes, and generally making himself an immovable obstacle to criminals—represented a physicality largely absent from more cerebral detectives of the period. Mannix demonstrated that sometimes solving crimes wasn’t about brilliant deduction but simply outlasting and outfighting the opposition—a testament to grit over forensic science.

8. Banacek (George Peppard)

Thomas Banacek solved impossible thefts and disappearances for insurance companies, collecting a percentage of the recovered value while displaying unflappable sophistication and an encyclopedic knowledge of obscure Polish proverbs. George Peppard played the Boston-based investigator (1972-1974) as an elegant puzzle-solver whose cases involved items vanishing under seemingly impossible circumstances—a football player disappearing in the middle of a play, a valuable car evaporating from a moving train, an experimental plane disappearing while being towed. His investigations relied on understanding both the mechanics of illusion and the psychology of misdirection rather than traditional evidence collection.

Banacek epitomized the detective as intellectual showman, dramatically revealing solutions to seemingly impossible crimes through reconstructions that explained how the seemingly magical disappearances were actually clever frauds. His method involved questioning witnesses, scrutinizing locations, and then mentally reconstructing crimes by asking not just how objects could vanish but why someone would want them to disappear in such complicated ways. The series highlighted how understanding human motivation—particularly greed and the desire to create “perfect” crimes—could be more important than physical evidence in solving mysteries designed specifically to confound traditional investigation.

9. Frank Cannon (William Conrad)

Detective Frank Cannon broke the physical stereotype of the television detective—overweight, middle-aged, and with a gourmet’s appreciation for fine food and wine, he nonetheless outthought and occasionally outfought criminals half his age and twice his agility. William Conrad’s portrayal (1971-1976) brought gravitas and intelligence to a character whose appearance caused suspects to underestimate him, much to their eventual regret. Cannon’s investigative approach relied heavily on his previous experience as a police officer, utilizing established networks, understanding criminal psychology, and applying pressure at exactly the right points to break cases.

“Cannon” presented a detective whose physical limitations necessitated reliance on intellect, experience, and psychological insight rather than action heroics, though the series didn’t shy away from showing Cannon holding his own in physical confrontations when necessary. His investigations typically involved establishing relationships with witnesses and suspects, carefully observing interpersonal dynamics, and detecting subtle inconsistencies in statements that revealed underlying truths. Cannon demonstrated that effective detective work often came down to experience—knowing which questions to ask, which threats carried weight, and when a seemingly insignificant detail actually represented the key to the entire case.

10. Harry O (David Janssen)

Harry Orwell (Harry O) carried a bullet lodged near his spine from a previous shooting, giving David Janssen’s semi-retired police detective a permanent limp and a philosophical outlook on crime and punishment rarely seen in the genre. Living in a beach house in San Diego (later Santa Monica), Harry supplemented his disability pension with private investigation work approached with a world-weary existentialism that set him apart from more enthusiastic counterparts. His physical limitations prevented traditional action-hero approaches to cases, forcing him to rely on psychological insight, carefully cultivated contacts, and a unique ability to understand both victims and perpetrators as complex human beings rather than case elements.

During its 1974-1976 run, “Harry O” presented investigations as much concerned with why crimes occurred as with who committed them, with Harry often developing empathy for both victims and perpetrators while still pursuing justice. His detection methods emphasized human connection—genuine conversations rather than interrogations, understanding life circumstances that led to criminal behavior, and recognizing patterns in human conduct that pointed toward likely suspects. Harry’s approach illustrated that sometimes the most effective crime-solving tool wasn’t scientific analysis but genuine human empathy—understanding people well enough to anticipate their actions, recognize their deceptions, and ultimately, reveal their secrets.

11. Baretta (Robert Blake)

“And dat’s the name of dat tune!” was the signature phrase of Tony Baretta, an unconventional undercover detective who lived with a cockatoo named Fred and solved crimes by immersing himself in the street life of the urban neighborhoods he protected. Robert Blake portrayed Baretta (1975-1978) as a detective who could seamlessly blend into any environment through disguises, street dialect, and a chameleon-like ability to adapt to different social contexts. His crime-solving relied not on evidence processing but on becoming part of the communities where crimes occurred, understanding their internal dynamics, and identifying perpetrators through direct engagement rather than distant analysis.

Baretta’s approach to detection emphasized that criminal investigations couldn’t be conducted remotely or theoretically—they required getting dirty, taking risks, and establishing authentic connections within communities most police officers only viewed from patrol cars. His methods included cultivating regular informants (notably the street-wise Rooster), assuming identities that gave him access to criminal networks, and creating scenarios that pressured suspects into revealing themselves. The series demonstrated that effective crime-solving often required breaking down the barrier between detective and community, suggesting that true understanding came only from immersion rather than observation.

12. Quincy, M.E. (Jack Klugman)

While most TV detectives of the era worked for police departments or as private investigators, Dr. Quincy approached crime-solving from the unique perspective of a medical examiner who refused to accept easy answers or convenient conclusions about suspicious deaths. Jack Klugman portrayed the passionate, often irascible coroner (1976-1983) as a crusader who saw his autopsy table as the starting point for investigations rather than merely a place to confirm obvious causes of death. Though he worked with medical tools, Quincy solved crimes through persistence and intuition rather than sophisticated forensics, frequently butting heads with his supervisor Dr. Asten and police homicide Lieutenant Monahan when his hunches contradicted their preferred conclusions.

“Quincy, M.E.” stood apart from other detective shows by focusing on the “why” and “how” of deaths rather than simply identifying perpetrators, with Quincy often uncovering public health dangers, systemic injustices, or institutional failures along the way. His investigative style combined medical knowledge with old-fashioned detective work—interviewing witnesses, visiting crime scenes, and pursuing leads long after being ordered to drop cases—making him a true hybrid of scientist and street detective. Quincy demonstrated that even in a seemingly scientific field like pathology, intuition and human understanding remained essential to discovering truth, particularly when that truth was inconvenient for those in power or challenged conventional wisdom about a case’s apparent resolution.

The detectives of the ’60s and ’70s remind us that before crime labs dominated police work, investigation was primarily about people—understanding their motivations, recognizing their patterns, and ultimately, outthinking them. These iconic characters solved crimes not through microscopes and databases but through something far more entertaining: distinctive personalities applying unique insights into human behavior. While today’s procedurals might showcase more realistic methods, they rarely capture the pure characterization and psychological chess matches that made these classic detectives so compelling. Their legacy continues to influence detective fiction across all media, reminding creators that while forensic science might solve cases, it’s the detectives themselves—flawed, persistent, and brilliantly intuitive—who solve crimes in ways that capture our imagination.