Before helicopter parenting, liability waivers, and the phrase “safety first” became ubiquitous, children of the 1960s and 1970s experienced a freedom that today’s kids might find hard to imagine. We roamed neighborhoods unsupervised, created games with whatever was at hand, and engaged in activities that would make modern parents gasp in horror. The bumps, bruises, and occasional trips to the emergency room were simply considered part of growing up. Let’s take a nostalgic look back at the childhood games and activities that defined a generation—and would likely trigger panic in today’s more cautious world.

1. Lawn Darts (Jarts)

Few toys epitomize dangerous ’60s and ’70s play equipment quite like lawn darts, those missile-like projectiles with weighted metal tips that children hurled skyward with abandon. The official game involved tossing these potential weapons toward plastic rings on the ground, scoring points for landing inside the target area. The actual gameplay often devolved into increasingly creative (and hazardous) throwing techniques, with minimal concern for tracking where other children might be standing. Mental Floss details the tragedy that came before these hazardous toys were banned.

After numerous injuries and several tragic deaths, lawn darts were banned for sale in the United States in 1988—one of the first toys officially deemed too dangerous to market. Modern versions exist with blunt plastic tips, but they lack the thrilling danger of the originals that could pierce shoe leather and embed themselves in backyard patios. The fact that many families still kept their sets for years after the ban, tucked away in garage rafters or basement storage, speaks to both the game’s popularity and the different approach to risk management in previous generations.

2. Red Rover

“Red Rover, Red Rover, send Jimmy right over!” This playground classic involved two lines of children holding hands to create human chains, with one child called to run full-force and attempt to break through the opposing line. Success meant choosing a captured player to bring back to your team; failure meant joining the enemy line. The game rewarded both speed and strategic selection of the “weakest link” in the opposing team’s chain. Pixies Did It recounts the swashbuckling origins of this game that dates back centuries and crosses several international borders.

Today’s concerns about collision injuries, hyperextended arms, and the psychological impact of being specifically targeted as the “weak link” have made Red Rover increasingly rare in school settings. The combination of full-speed running, sudden impact, and resistance created a perfect storm for dislocated shoulders and wrist injuries that most modern schools aren’t willing to risk. The game also allowed for subtle social dynamics that could border on bullying, with less popular children either chosen as targets too frequently or left standing unchosen until the end.

3. Unsupervised Water Activities

Summer days often meant heading to local swimming holes, ponds, or creeks with nothing but a towel and perhaps a sandwich wrapped in wax paper. Parents would send children off with a casual “be home by dinner” while kids as young as seven or eight ventured to natural water sources where depths were unknown, currents unpredictable, and lifeguards nonexistent. Improvised rope swings hanging from trees created thrilling but hazardous entry points, with minimal checking for submerged objects before the first brave jumper tested the waters. Lake Life State of Mind lists some other lake activities to consider taking up, with abundant supervision.

The lack of supervision extended to backyard pools, where neighborhood children gathered with minimal adult oversight during hot summer days. Diving contests, breath-holding competitions, and games like “Colors” (where one child called out colors while others rushed to touch something matching that color before returning to the pool wall) created numerous opportunities for accidents. Today’s strictly supervised swim times, swim lessons as a prerequisite for water access, and fenced pools with locked gates represent a complete reversal of the carefree water play that defined summer for previous generations.

4. Sledding Down “Suicide Hill”

Every town seemed to have its legendary sledding spot—an impossibly steep hill with obstacles, sudden drops, or a road at the bottom that added an element of genuine peril to winter fun. These unofficial sledding destinations earned ominous nicknames like “Suicide Hill” or “Breaker Hill,” their danger enhancing their appeal to thrill-seeking children. Homemade sleds and toboggans often lacked steering mechanisms or brakes, leaving rocks, trees, and telephone poles as the default stopping method.

Modern communities have largely eliminated unregulated sledding through restrictions, liability concerns, and the grooming of designated “safe” sledding areas. The improvised sleds of yesteryear—cafeteria trays, metal garbage can lids, or flattened cardboard boxes—have been replaced by commercially designed equipment with safety features and clear usage guidelines. While children still sled, the unsupervised dawn-to-dusk sledding adventures that once occurred after every substantial snowfall have largely disappeared from American childhood.

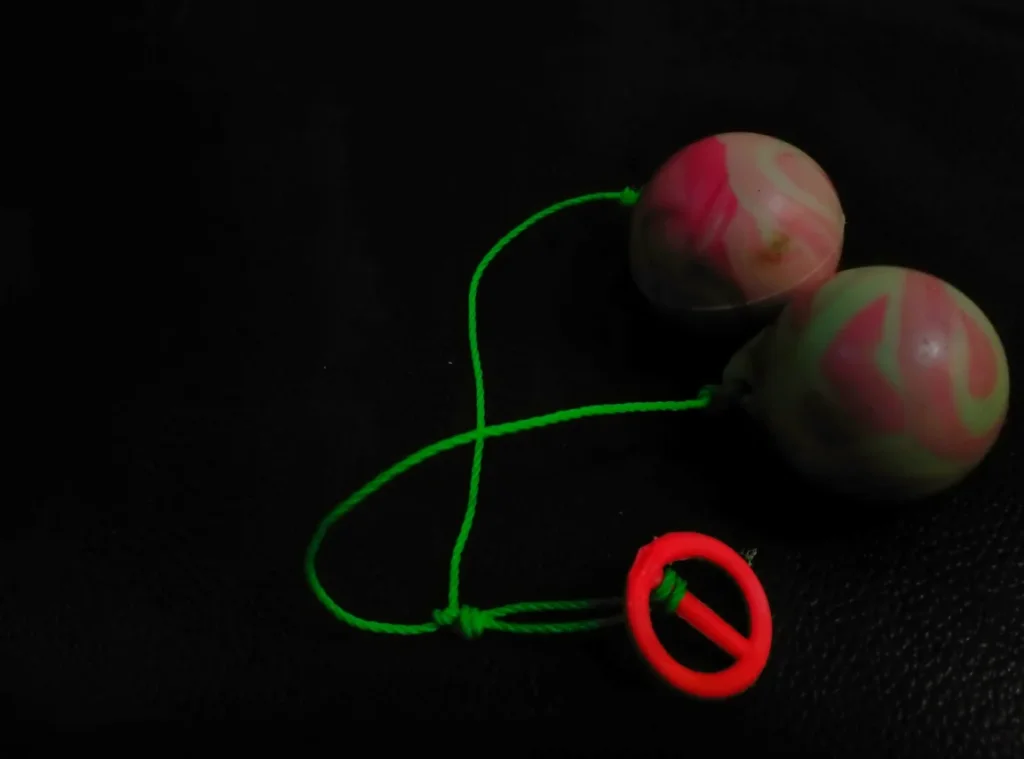

5. Clackers

These deceptively simple toys consisted of two acrylic balls attached to each end of a string, which the player would rhythmically bounce up and down to create a satisfying “clack” sound as the balls collided. The objective was to get the balls clacking above and below the hand in an impressive display of coordination. What made these toys particularly hazardous was the acrylic material, which could shatter into sharp fragments when the balls hit each other with sufficient force—often sending shards flying directly toward the user’s face.

Clackers were eventually pulled from the market after being classified as “mechanical hazards,” but not before countless children had experienced the unique pain of taking a solid hit to the wrist bone from a wildly swinging acrylic ball. Modern variants exist with softer plastic or lighter materials, but they lack the substantial heft and potentially injurious velocity that made the originals simultaneously satisfying and dangerous. The distinct sound of properly operated clackers can still trigger nostalgic memories for those who mastered them without injury.

6. Neighborhood-Wide Games After Dark

Summer evenings in the ’60s and ’70s often featured massive games of Kick the Can, Ghost in the Graveyard, or Flashlight Tag that spanned entire neighborhoods and continued well past sunset. Dozens of children would scatter across multiple blocks, hiding behind parked cars, crouching in bushes, or climbing trees—all with minimal supervision and no way to communicate except through prearranged signals or designated “home bases.” The boundaries might extend for blocks, with only the unwritten rule that certain neighbors’ yards were off-limits.

Today’s parents would likely be horrified at the thought of elementary school children racing through darkened neighborhoods, potentially entering strangers’ yards, and being completely out of sight or communication range for hours. The combination of stranger danger awareness, traffic safety concerns, and the connectivity expectations of cell phones has made these sprawling nighttime games virtually extinct. Modern organized activities with adult supervision, defined boundaries, and scheduled end times bear little resemblance to the improvised, boundary-pushing freedom of these after-dark adventures.

7. Dodgeball with Hard Balls

The dodgeball of previous generations wasn’t played with the soft foam balls found in today’s physical education classes but with kickballs, volleyballs, or specialized rubber balls that could leave impressive welts when thrown with full force. The game celebrated both athletic prowess and a certain tolerance for pain, with the hardest throwers earning playground respect regardless of their targets’ discomfort. Various regional versions added extra elements of danger, such as “Bombardment,” which eliminated the safety of boundary lines in favor of a confined free-for-all.

Modern concerns about bullying, targeted aggression, and the physical and emotional impact of essentially “hunting” less athletic children have led many schools to ban traditional dodgeball entirely. When permitted, the game has been modified with softer balls, stricter throwing rules, and more emphasis on dodging than throwing—transformations that previous generations might view as removing the very essence of the game. The thrill of successfully catching a hard-thrown ball, the adrenaline rush of being the last player standing, and even the character-building aspects of learning to take a hit have been sacrificed in the name of universal inclusion and physical safety.

8. Bike Stunts Without Helmets

Bicycle ownership in the ’60s and ’70s came with minimal safety equipment but maximum freedom, as children constructed increasingly elaborate ramps and obstacle courses for stunt performances. Plywood boards propped on bricks or cinder blocks created primitive jump ramps, while daring riders attempted wheelies, no-handed rides, and standing on seats—all without helmets, knee pads, or any protective gear whatsoever. The inevitable falls and injuries were considered valuable lessons rather than reasons to limit risky riding.

Neighborhood bike culture often featured informal competitions to determine who could perform the most impressive (and dangerous) stunts, with older children teaching younger ones techniques that parents were often blissfully unaware of. Today’s carefully supervised bike riding, with mandatory helmets, elbow and knee protection, and adult-approved routes stands in stark contrast to the self-directed, risk-embracing bicycle culture that once defined childhood independence. While serious head injuries have undoubtedly been prevented by modern safety practices, something of the self-reliance and risk assessment that children developed through unsupervised cycling has been lost as well.

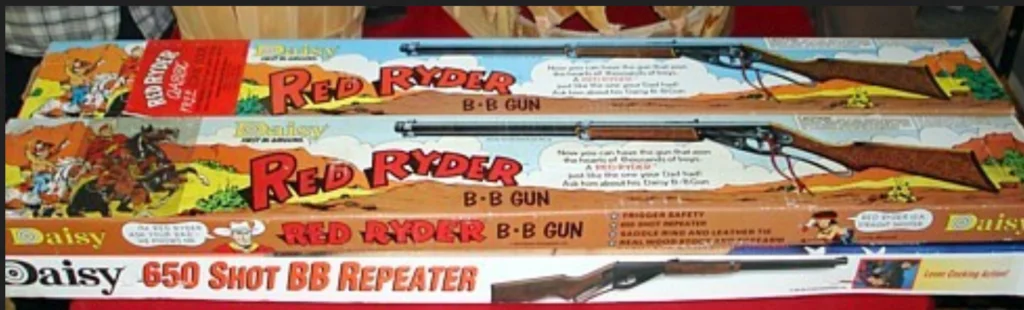

9. BB Gun Wars

In rural and suburban areas, older children and young teenagers sometimes engaged in the supremely ill-advised activity of BB gun “wars,” using low-powered air rifles to shoot at each other from a distance. Participants typically established ground rules about acceptable shooting zones (usually below the neck) and minimum distances, but these improvised safety measures provided minimal protection from the potential for serious eye injuries or other permanent damage. That relatively few children were blinded or seriously injured seems more attributable to luck than judgment.

The concept of children possessing and using air rifles with minimal supervision is itself foreign to many modern parents, let alone the idea of intentionally shooting them in the direction of other human beings. Today’s strict zero-tolerance policies regarding weapons at schools, heightened awareness of gun safety, and the availability of non-projectile alternatives like laser tag or Nerf guns have relegated actual BB gun confrontations to the realm of “dangerous things people somehow survived.” The childhood BB gun experience now typically involves adult supervision, proper safety instruction, and clearly defined non-human targets.

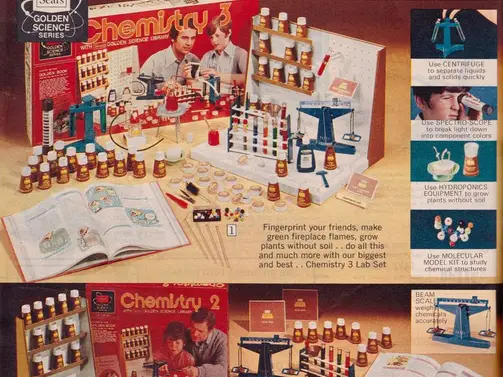

10. Chemistry Sets with Real Chemicals

The chemistry sets available to children in the 1960s and early 1970s contained substances that would never be approved for home use today, including chemicals that could cause genuine explosions, toxic reactions, or burns when mishandled. These sets encouraged open-ended experimentation rather than following safety-tested instructions, with many children using them to create smoke bombs, mild explosives, or noxious gases that they tested in basements and backyards with minimal ventilation and no protective equipment.

Modern chemistry sets have been so thoroughly sanitized that many contain no chemicals at all, instead focusing on innocuous reactions using household substances like vinegar and baking soda. The genuine (if small-scale) danger that made original chemistry sets so engaging—the possibility that something might actually go dramatically wrong if you weren’t careful—has been engineered away in favor of guaranteed safe outcomes. While understandable from a liability perspective, this change has removed the authentic scientific experience of respecting potentially dangerous materials and learning proper laboratory discipline through meaningful consequences.

11. Playing in Construction Sites

Partially built homes, road construction projects, and other building sites served as irresistible playgrounds for children of previous generations, who clambered over dirt mounds, balanced on foundation walls, and explored unfinished structures without permission or supervision. Weekend adventures might include walking across support beams, sliding down dirt piles on pieces of cardboard, or collecting discarded construction materials for fort building—all in environments filled with exposed nails, unstable surfaces, and heavy equipment.

Today’s construction sites are typically surrounded by security fencing, monitored by surveillance cameras, and clearly marked with “No Trespassing” signs that reflect both safety concerns and liability issues. Parents are far more likely to report unsecured construction areas and to explicitly forbid children from entering them under any circumstances. The unstructured play and risk assessment that children once practiced in these environments—deciding which beams could hold their weight or which dirt slopes were too steep to climb—has been replaced by manufactured playground equipment with predictable challenges and tested safety limits.

12. Hitchhiking

Perhaps no childhood activity of the ’60s and ’70s would raise more alarm today than the casual hitchhiking practiced by teenagers and sometimes even younger children. In many communities, especially rural areas, catching rides with strangers was a commonplace method of transportation rather than a frightening risk. Young people might hitchhike to swimming holes, movie theaters, or friends’ homes miles away, with parents either unaware or unconcerned about this practice.

The dramatic shift in attitudes toward hitchhiking reflects broader societal changes around stranger danger, awareness of predatory behavior, and the expectation that children’s whereabouts should be known at all times. Modern parents would likely consider allowing a teenager to hitchhike as a form of negligence, while children themselves have internalized messages about the dangers of accepting rides from unknown adults. What was once a practical transportation solution and even a minor adventure has become an almost unthinkable risk, representing perhaps the starkest example of how childhood freedom has been curtailed in the name of safety.

Looking back at these activities provokes mixed emotions for those who experienced them firsthand. While few would argue for the return of lawn darts or truly dangerous chemistry sets, many wonder if today’s emphasis on structured, supervised, and safety-first childhood has overcorrected, eliminating not just physical risk but also valuable opportunities for independence, decision-making, and natural consequences. Perhaps the most balanced perspective acknowledges both the real dangers that existed in these bygone activities and the genuine developmental benefits that came from navigating risk in an era before childhood was quite so carefully curated.