Long before the internet transformed how we access information, libraries were magical kingdoms of knowledge, adventure, and community. The 1970s represented a golden age of library culture, when these public spaces were far more than just repositories of books—they were vibrant community centers that shaped entire generations of young readers and learners. These sanctuaries of knowledge offered experiences that were simultaneously educational, social, and deeply personal.

1. Card Catalog Adventures

The massive wooden card catalog was a child’s first introduction to research and organization, a tactile treasure hunt of information that required genuine detective skills. Each drawer contained hundreds of meticulously typed cards, with children learning to navigate alphabetical and subject classifications through a hands-on process. Pulling out drawers, sliding cards, and tracking down book locations became an exciting puzzle that taught research skills long before computers existed. American Libraries Magazine turns the page on exploring this innovation’s nuanced history.

Librarians would patiently teach children how to use these complex filing systems, transforming what could have been a mundane task into an educational adventure. The satisfying sound of wooden drawers sliding open, the smell of aged paper, and the sense of accomplishment when finding the exact card you needed created a memorable sensory experience. Card catalogs were more than information retrieval systems—they were gateways to endless worlds of discovery.

2. Summer Reading Programs

Before digital tracking and online challenges, summer reading programs were beautifully analog experiences that motivated children to read voraciously. Libraries would create elaborate tracking systems with colorful charts, stickers, and sometimes even prizes like free pizzas or movie tickets for completing reading goals. These programs transformed reading from a school requirement into an exciting personal challenge. According to TImes Union, this practice is enjoying some steady resurgence.

Children would proudly display their reading logs, competing with friends and siblings to read the most books during summer vacation. Librarians became cheerleaders of literacy, designing creative themes and decorations that made the library feel like a special destination. The programs weren’t just about quantity but celebrating the joy of reading, creating lifelong love of books for countless children.

3. Storytime as Community Ritual

Library storytime was a cherished weekly ritual that went far beyond simple book reading. Librarians were performance artists who transformed children’s literature into magical experiences, using different voices, dramatic gestures, and interactive elements that captivated young audiences. These sessions were social experiences where children learned listening skills, made friends, and discovered the power of narrative. Foundations Worldwide Inc. stresses the importance of storytime not just in libraries but everywhere children receive care.

The carefully curated selection of books reflected contemporary social values, introducing children to diverse stories and perspectives. Storytime was often one of the few free, accessible community activities for families, creating a democratic space where all children could participate regardless of economic background. Librarians became trusted community figures who nurtured childhood imagination and learning.

4. Audiovisual Wonderland

1970s libraries were multimedia experiences that went far beyond books. Children could borrow record albums, filmstrips, educational cassettes, and even early educational films. The audiovisual section felt like a technological wonderland, with specialized equipment for experiencing different media. Learning became a multisensory experience that expanded beyond traditional reading.

These resources were particularly valuable for families who couldn’t afford expensive home entertainment systems. Children could explore music, educational documentaries, and language learning materials that were otherwise unavailable. The audiovisual section represented a democratization of knowledge, providing access to cultural experiences that transcended economic barriers.

5. Quiet Spaces for Personal Exploration

Libraries offered something increasingly rare in modern childhood—genuine unstructured personal time. Children could explore shelves independently, discover books by accident, and spend hours reading without adult interference. These quiet spaces taught self-direction, curiosity, and the joy of independent learning in a way structured educational environments rarely could.

The library’s peaceful atmosphere allowed children to develop personal reading preferences and explore topics of genuine interest. Comfortable reading nooks, soft lighting, and the unspoken rule of quiet created an almost sacred space for intellectual exploration. Unlike noisy home environments or structured classrooms, libraries offered a unique sanctuary for personal discovery.

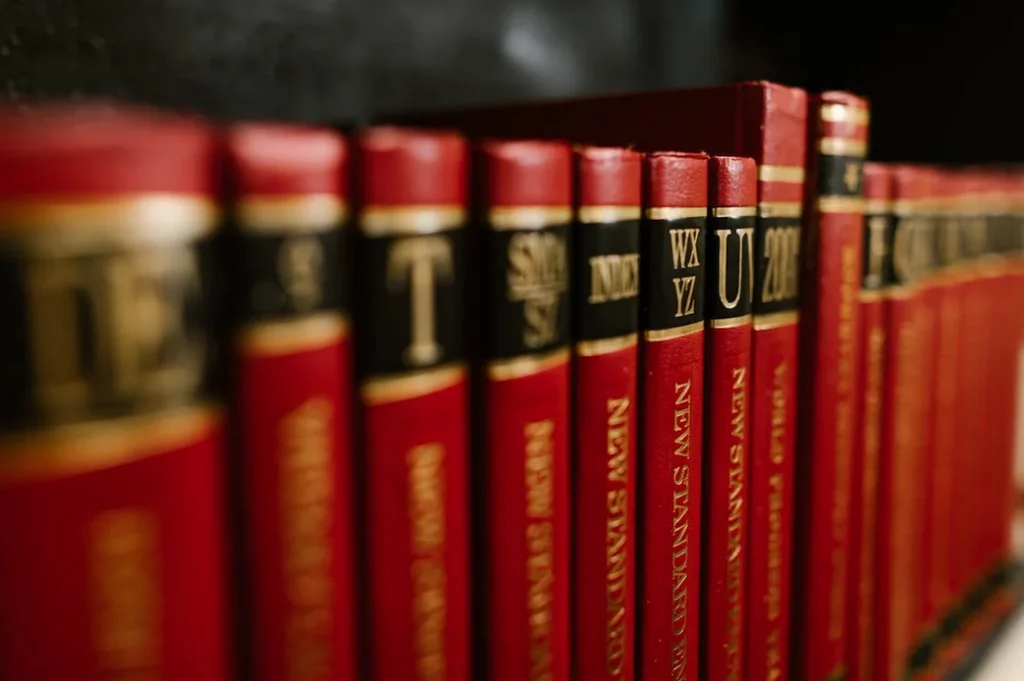

6. Encyclopedias and Reference Sections

Before internet search engines, library reference sections were portals to comprehensive knowledge. Massive encyclopedia sets became windows to the world, with children spending hours exploring everything from ancient civilizations to scientific discoveries. These resources taught research skills and satisfied natural childhood curiosity in ways modern digital sources cannot replicate.

The physical act of pulling heavy reference volumes, carefully turning pages, and cross-referencing information created a more intentional learning experience. Children learned patience, systematic research, and the joy of deep, focused exploration. Reference sections weren’t just information repositories—they were laboratories of intellectual curiosity.

7. Community Bulletin Boards

Library bulletin boards were analog social networks that connected community members in meaningful ways. Local classes, events, volunteer opportunities, and community notices created a vibrant information ecosystem. For children, these boards represented early lessons in community engagement and understanding local social dynamics.

Parents would browse these boards while children explored books, creating a holistic family experience. The bulletin boards reflected local culture, showcasing everything from Little League signups to art classes and cultural events. They represented grassroots communication in an era before digital connections, teaching children about community participation.

8. Librarians as Trusted Mentors

Librarians in the 1970s were more than information managers—they were trusted community mentors who took genuine interest in children’s intellectual development. They would carefully curate book recommendations, help children explore new interests, and create personalized reading experiences. These relationships often transcended the library, with librarians becoming trusted adult figures.

Many children discovered lifelong passions through librarian recommendations, whether in literature, science, history, or art. Librarians understood individual children’s interests and could suggest books that expanded their horizons while respecting their current reading levels. They were patient teachers who made learning feel like an exciting adventure.

9. Interlibrary Loan Magic

The interlibrary loan system represented a fascinating collaborative network that seemed almost magical to children. If a specific book wasn’t available locally, librarians could request it from other libraries, sometimes from entirely different states. This system taught children about broader information networks and the interconnectedness of knowledge.

Waiting for a requested book became an exciting experience, with children learning patience and anticipation. The process revealed that knowledge wasn’t confined to local boundaries but existed in a broader, collaborative ecosystem. Interlibrary loans were early lessons in information sharing and community cooperation.

10. Free Access and Easy Learning

Libraries represented one of the most genuinely democratic institutions of the 1970s, providing free access to knowledge regardless of economic background. Children from all socioeconomic levels could access the same resources, learn the same information, and explore the same worlds. This universal access was revolutionary in an era of increasing social stratification.

The library card became a symbol of personal empowerment, allowing children to curate their own learning experiences. No monetary transaction was required, creating a pure exchange of knowledge. Libraries embodied the idea that learning is a fundamental right, not a privilege reserved for the wealthy.

11. Craft and Activity Workshops

Many libraries expanded beyond book lending to offer free workshops and activities for children. From puppet-making classes to reading clubs, summer science demonstrations to cultural celebration events, libraries became dynamic community centers. These programs provided enriching experiences that complemented formal education.

Children could explore interests outside traditional academic environments, discovering talents and passions through library-sponsored activities. The workshops were typically free or low-cost, making them accessible to entire communities. Libraries transformed from quiet book repositories to vibrant learning centers.

12. Microfiche and Research Excitement

The mysterious world of microfiche represented technological wonder for 1970s children. These miniature film slides containing compressed information felt like secret code waiting to be deciphered. Special microfiche readers in library research sections created an atmosphere of scientific exploration, teaching children advanced research techniques.

Learning to use microfiche readers became a rite of passage, with librarians patiently teaching complex navigation skills. These resources allowed access to historical newspapers, academic journals, and research materials that were otherwise unavailable. Microfiche represented the cutting edge of information technology, inspiring children’s technological curiosity.

Libraries in the 1970s were more than buildings filled with books—they were vibrant community ecosystems that nurtured intellectual curiosity, provided democratic access to knowledge, and created lasting memories for an entire generation. These spaces represented something profound: the belief that learning is a lifelong adventure best pursued with curiosity, patience, and joy.