The American highway system of the 1970s was dotted with attractions that beckoned travelers with promises of the bizarre, the educational, and the utterly perplexing. These weren’t the polished theme parks or curated museums we know today—they were passion projects, entrepreneurial gambles, and sometimes just plain odd manifestations of individual obsessions. With gas station maps as their guides and wood-paneled station wagons as their vessels, families would veer off the interstate at the sight of hand-painted signs or towering oddities, often finding themselves in experiences that straddled the line between charming and unsettling. These attractions captured a uniquely American spirit—part hucksterism, part genuine wonder—that has largely faded from our homogenized travel landscape.

1. Mystery Spots and Gravity Hills

Scattered across America, these physics-defying locations promised to show visitors places where the normal rules of gravity supposedly didn’t apply. Water appeared to flow uphill, people seemed to stand at impossible angles, and balls would roll “up” inclined surfaces while tourists watched in amazement. These attractions often featured ramshackle wooden structures built at disorienting angles, with tour guides demonstrating various “supernatural” phenomena using rehearsed patter that hadn’t changed since the 1950s. The scientific explanations involving optical illusions and manipulated perspectives were readily available but seldom emphasized—the mystery was the selling point. California Through My Lens explores the subtleties that made this particular spot so successful.

What made these spots both fascinating and slightly unsettling was how committed the operators were to their pseudoscientific narratives about “magnetic vortexes” or “intersecting cosmic forces.” Visitors left with souvenir certificates confirming they had witnessed something paranormal, feeding into a cultural moment when Americans were particularly receptive to tales of the unexplained. The cramped quarters of these attraction buildings, often located in remote wooded areas with limited signage until you were nearly upon them, created an atmosphere where reality felt genuinely suspended—even if it was just your perception being cleverly manipulated.

2. Reptile Gardens and Alligator Farms

Long before exotic animal ethics became a mainstream concern, roadside reptile attractions invited travelers to gaze upon collections of snakes, lizards, and alligators housed in facilities that ranged from surprisingly professional to distressingly makeshift. The star attractions were typically the alligator wrestling shows, where sunburned men in khaki shorts would demonstrate various holds on bewildered reptiles while delivering educational commentary punctuated by wisecracks. Gift shops inevitably sold baby alligator heads preserved in acrylic, snake skins, and various preserved specimens that would raise eyebrows (and possibly legal concerns) today. South Dakota Travel explores the history and evolution of reptile museum through a photographic lens.

The unsettling quality of these attractions stemmed from the contrast between the promotional materials—often featuring cartoon alligators wearing sunglasses—and the reality of concrete pits filled with lethargic reptiles in varying states of care. Many facilities began with genuine conservation or educational intentions before economic realities pushed them toward more sensational presentations. The distinctive smell of these places—a mixture of water that needed changing, reptile food, and the peculiar musty odor of the animals themselves—created a sensory experience that lingered long after visitors returned to their cars, often with a newly purchased rubber snake wrapped around someone’s neck.

3. Deserted Ghost Towns

The ’70s saw a boom in preserved (or reconstructed) ghost towns capitalizing on Americans’ fascination with the Wild West and frontier history. These attractions ranged from authentic abandoned mining communities to hastily assembled collections of salvaged buildings arranged to resemble historical settlements. Visitors wandered through dusty streets, peering into recreated saloons with mannequins frozen in mid-poker game or barbershops with ominously stained straight razors displayed on counters. Often the experience included treasure panning opportunities where children were guaranteed to find “real gold” (brass-colored flakes) in exchange for a modest fee. Travel US News has a list of some must-see ghost towns to visit.

What made these attractions both compelling and eerie was their liminal status—not quite authentic history and not quite amusement parks, they existed in a twilight zone of historical approximation. The creepiest featured wax figures with expressions that had melted slightly in summer heat, positioned in tableau scenes meant to capture daily life but inadvertently creating unsettling frozen moments. The recorded player piano music that often echoed through empty streets, combined with the knowledge that these towns represented genuine economic collapse for their original inhabitants, created an atmosphere of melancholy that even the most enthusiastic tour guide couldn’t fully dispel.

4. Family-Run Wax Museums

Long before Madame Tussauds perfected the art of hyper-realistic celebrity replicas, small-town wax museums offered travelers the chance to stand alongside historical figures and pop culture icons—or at least waxy approximations that bore passing resemblances to their subjects. These museums often specialized in scenes of historical significance or tableaus from Bible stories, with presidential assassination recreations being particularly popular despite (or perhaps because of) their macabre nature. Each display typically featured dramatic lighting and a small plaque with information that hadn’t been updated since the attraction’s founding, regardless of changing historical interpretations.

The unintentional horror factor of these attractions came from the quality of the figures themselves—created with varying degrees of skill and maintained with limited resources. Eyes that didn’t quite focus correctly, skin textures that looked simultaneously too shiny and too matte, and wigs that had shifted slightly over time created an uncanny valley effect avant la lettre. The practice of reusing bodies and merely swapping heads when exhibits changed meant proportions were often subtly wrong, with historical pioneers sometimes sporting hands that belonged to movie stars. Visitors would emerge from these dimly lit spaces blinking in the sunlight, carrying memories of Abraham Lincoln’s eerily smooth complexion or Marilyn Monroe’s vacant stare.

5. Prehistoric Concrete Dinosaurs

Looming beside highways or crouching in wooded roadside parks, enormous concrete dinosaurs represented one of the most visible categories of American roadside attractions. These behemoths—often constructed in the 1960s but enjoying continued popularity throughout the ’70s—reflected paleontological understanding that was already outdated when they were built, featuring tail-dragging postures and colors chosen more for visibility than accuracy. Many served as promotional tools for nearby gift shops where children could purchase plastic dinosaur figurines, geodes, and “dinosaur egg” candies after climbing on the outdoor sculptures.

The strange appeal of these attractions lay in their deliberate displacement—prehistoric creatures frozen in time beside modern highways, creating a jarring juxtaposition of time periods. At night, the most elaborate dinosaur parks took on a particularly unsettling quality, with strategic lighting casting long shadows from tyrannosaurus jaws or illuminating stegosaurus plates from below. The concrete construction meant these attractions weathered unevenly, developing cracks and discoloration that sometimes gave the impression of disease or decay, particularly in humid climates where moss and lichen cultivated green patches on gray dinosaur skin.

6. Mystery Houses and Winchester Mansions

Architectural oddities marketed as “mystery houses” drew visitors with promises of staircases leading nowhere, doors opening into solid walls, and rooms where marbles rolled uphill due to slanted construction. The most famous example—the Winchester Mystery House in California—inspired numerous imitators across the country, each with their own legends about eccentric builders compelled by supernatural forces or grief to create structurally bewildering homes. Tours typically emphasized supernatural elements over the more mundane (but often equally interesting) architectural and historical context.

The disorienting physical experience of moving through these spaces created genuine unease that publicity materials leaned into heavily, with brochures featuring shadowy photographs and hints of ghostly presences. Something about these attractions triggered a particularly American anxiety about houses—supposedly safe domestic spaces—harboring secrets or threatening to trap visitors in their labyrinthine layouts. The tour guides, often dressed in period costume and speaking in hushed tones about mysterious deaths or supernatural phenomena, cultivated an atmosphere where rational visitors found themselves genuinely startled by ordinary house settling noises or unexpected drafts.

7. Criminally Focused Wax Museums and Death Scenes

A peculiar subset of roadside attractions focused exclusively on famous crimes, murderers, and execution methods, offering visitors glimpses of humanity’s darkest moments recreated in wax and theatrical lighting. These museums featured surprisingly detailed depictions of crime scenes, electric chairs with wax figures mid-execution, and recreations of prison cells housing infamous criminals. Located strategically near more family-friendly attractions, they tempted visitors with promises of educational historical content that actually veered closer to exploitation horror.

The unsettling nature of these attractions was amplified by their presentation as educational experiences, complete with informational plaques discussing forensic evidence while displays showed graphic crime scene details. The contrast between the often cheerful exterior buildings—sometimes featuring cartoon prison stripes or playful guillotine imagery—and the genuinely disturbing content inside created cognitive dissonance for visitors. Parents would debate whether children should be allowed inside, often compromising by rushing them past certain displays while lingering at others deemed less traumatizing, creating a strange hierarchy of acceptable horrors for family consumption.

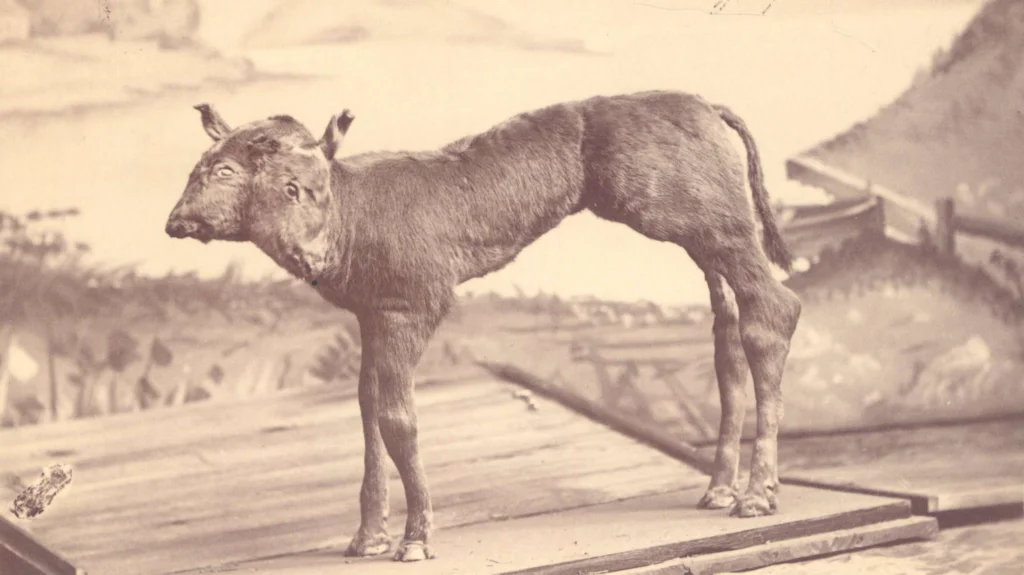

8. Two-Headed Calf Museums

Across rural America, small museums dedicated to biological oddities invited travelers to view preserved specimens of two-headed calves, six-legged sheep, and other genetic anomalies presented as marvels of nature. These collections often began as a single preserved specimen in a general store or gas station before expanding to dedicated buildings housing dozens of jarred and taxidermied curiosities. The accompanying signage typically offered minimal scientific explanation, instead emphasizing the “believe it or not” quality of these natural mutations—sometimes with religious undertones about God’s mysterious ways.

The profound strangeness of these attractions stemmed from their presentation of genuine biological specimens as entertainment, occupying an uncomfortable space between science education and carnival sideshow. Visitors experienced a complex mix of emotions—compassion for the animals, scientific curiosity about the causes, and an uneasy awareness of their own voyeuristic participation. The preservation methods used were often rudimentary, resulting in discolored specimens floating in cloudy formaldehyde or taxidermy that had degraded over decades of display, adding a layer of physical decay to the already emotionally complicated viewing experience.

9. Rock Shops with “Museum” Sections

Geology-themed gift shops proliferated along highways in desert states, luring travelers with promises of seeing the world’s largest quartz crystal or most perfect geode. These establishments typically featured a carefully constructed division—a free “museum” area showcasing impressive mineral specimens that funneled visitors directly into extensive gift shops selling tumbled stones and jewelry. The museum sections often included dubious claims about healing properties of various crystals alongside legitimate geological information, creating an educational experience heavily seasoned with pseudoscience.

The slightly off-putting quality of these attractions came from their aggressive commercialization thinly veiled as education, with “museum guides” seamlessly transitioning from geological explanations to sales pitches. The physical spaces often featured dramatic lighting that made ordinary rocks appear extraordinary and black light rooms where certain minerals glowed in supernatural-seeming ways. The pervasive smell of incense and the sound of tinkling new age music created an atmosphere that felt deliberately engineered to encourage impulse purchases of amethyst chunks or apache tears, playing on visitors’ desires to take home something meaningful from their travels.

10. Wall Drug and Copycat Mega-Stops

The legendary Wall Drug in South Dakota inspired numerous imitators—sprawling roadside complexes that began as simple service stations before expanding into labyrinthine collections of gift shops, restaurants, and bizarre attractions. These businesses saturated highway approaches with hundreds of billboards building anticipation for attractions like animated T-Rex displays, giant jackalopes visitors could sit on, or world-record-claiming collections of mundane objects. The overwhelming scale and sensory assault of these stops turned simple rest breaks into hour-long diversions through carefully designed commercial mazes.

What made these mega-stops both fascinating and disconcerting was their status as artificial destinations—places that existed solely to capture highway travelers and separate them from their vacation dollars through sheer persistence and scale. The aggressive marketing created expectations that the actual experience rarely met, yet there was something genuinely impressive about the single-minded determination behind these entrepreneurial visions. The mixture of authentic frontier history, manufactured nostalgia, and commercial opportunism created spaces where visitors never quite knew if they were experiencing something genuine or being expertly manipulated—a uncertainty that defined much of American roadside culture.

11. Frontier Village Theme Parks

These small-scale Western-themed parks offered budget-friendly alternatives to Disneyland, featuring stunt shows with staged gunfights, can-can dance performances, and panning for gold activities. Often built around authentic historical buildings or reconstructions, these attractions attempted to recreate frontier towns with varying degrees of historical accuracy and production value. Costumed performers wandered the grounds staying in character while interacting with visitors, creating an immersive experience despite limited resources and facilities that were often showing their age by the 1970s.

The slightly unsettling aspect of these parks emerged from their shifting cultural context—what began as straightforward celebrations of pioneer spirit in the 1950s felt increasingly complicated by the 1970s as American attitudes toward Western expansion and treatment of indigenous peoples evolved. The performances often reflected outdated stereotypes and historical perspectives that created uncomfortable moments for increasingly aware visitors. The physical infrastructure of these parks frequently suffered from limited maintenance, with weathered buildings, fading paint, and mechanical elements that functioned sporadically, creating an atmosphere of faded glory that seemed to comment unintentionally on the mythology they celebrated.

12. Last Chance Gas Station Museums

Some of the most distinctive roadside experiences weren’t officially attractions at all but evolved organically as gas station owners accumulated collections of local artifacts, unusual objects, or personal obsessions that gradually took over their businesses. These unofficial “museums” might showcase everything from arrowhead collections to taxidermied local wildlife to the owner’s hand-carved wooden figures, displayed in glass cases between the potato chips and motor oil. Without professional curation or climate control, these collections developed according to inscrutable personal logics, sometimes growing until they dominated the original business purpose.

The peculiar charm and subtle unease these places generated came from their deeply personal nature—visitors were essentially being invited into someone’s obsession, curated according to standards that might make sense only to the creator. The collections often reflected disappearing local knowledge or skills, preserved haphazardly by individuals rather than institutions. Conversations with the proprietors could be as fascinating as the collections themselves, offering glimpses into worldviews shaped by isolation and deep connection to specific landscapes. These stops represented a vanishing America where commerce and personal passion hadn’t yet been fully separated, where a simple fuel purchase might unexpectedly lead to examining a jarred two-headed snake or hearing a thirty-minute monologue about pioneering families in the county.

These roadside attractions represented something quintessentially American—the freedom to express individual visions, however eccentric, and the entrepreneurial spirit that saw commercial potential in the unusual and unexplained. Their appeal came from authenticity rather than polish, offering experiences that couldn’t be precisely replicated or franchised. As interstate highways increasingly bypassed these attractions and entertainment became more homogenized, they began disappearing from the American landscape, taking with them a peculiar blend of commerce, creativity, and cultural expression that straddled the line between kitsch and genuine wonder. Today’s travelers might find these places unsophisticated or unconvincing, but they captured a moment when Americans were still willing to pull over for the promise of seeing something they couldn’t quite believe.