Once upon a time, these restaurant chains dominated American highways and suburban landscapes, serving up everything from steaks to sundaes with their distinctive branding and memorable dining experiences. Today, they exist primarily in the realm of nostalgia—some completely vanished, others reduced to a handful of locations from their former empires. Behind each restaurant chain’s decline lies a unique story of changing tastes, management missteps, economic pressures, or cultural shifts that transformed these once-thriving establishments into cautionary tales of the volatile food service industry. Here’s a look at what really happened to 13 beloved restaurant chains that once fed America but couldn’t stand the test of time.

1. Howard Johnson’s

With its distinctive orange roof and weathervane spire, Howard Johnson’s was once America’s largest restaurant chain, boasting over 1,000 locations during its 1970s peak. The combination of family-friendly restaurants and motor lodges made “HoJo’s” a fixture of the American roadside, famous for its 28 ice cream flavors and fried clam strips. The chain’s decline began when the company was sold to Imperial Group in 1979, followed by a series of ownership changes that prioritized the hotel business over restaurants. American Business History puts into perspective the sheer scope of this former titan of the industry.

Howard Johnson’s failure to modernize its menu and decor as competitors evolved left it feeling dated to younger consumers seeking fresher options. The reliance on highway locations became a liability as the interstate system matured and travelers gained more dining choices. By the 1990s, most Howard Johnson’s restaurants had closed, with the final original location in Lake George, NY shuttering in 2022, marking the end of an American dining institution that had served generations of travelers since 1925. What remains today is merely the hotel brand, operating under completely different ownership with no connection to the restaurants that once made the name famous.

2. Steak and Ale

Founded in 1966 by Norman Brinker (who later developed Chili’s), Steak and Ale revolutionized casual dining by offering affordable steaks in a medieval-themed setting complete with a salad bar—a novel concept at the time. The chain expanded rapidly through the 1970s and 1980s, becoming known for its prime rib, Tudor-style buildings, and hospitable service that made special occasions accessible to middle-class diners. The beginning of the end came when Brinker sold the chain to Pillsbury in 1976, which eventually merged it with Bennigan’s. The Takeout takes a bite out of restaurant history to trace this chain’s full, delectable history.

The chain’s downfall accelerated when parent company Metromedia Restaurant Group filed for bankruptcy in 2008, abruptly closing all remaining Steak and Ale locations overnight. Employees reportedly arrived at work to find doors locked and no warning of the closure. The chain suffered from menu stagnation as competitors like Outback Steakhouse and Texas Roadhouse emerged with similar offerings and more modern appeal. Despite periodic announcements about potential revivals, including a 2019 announcement from Bennigan’s parent company, Steak and Ale remains a memory, remembered for popularizing several restaurant concepts now considered industry standards.

3. Chi-Chi’s

This Mexican restaurant chain brought its “fiesta-style” dining experience to the Midwest and East in the 1970s and 1980s, when Mexican cuisine was still novel in many American markets. At its peak, Chi-Chi’s operated over 210 locations, famously serving complimentary chips and salsa with massive chimichangas and its signature fried ice cream dessert. The chain’s troubles began with increased competition from fresher, more authentic Mexican concepts and accelerating financial problems in the early 2000s, leading to a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing in October 2003. Just recently, though, Mental Floss reported on a comeback this chain is determined to make.

Chi-Chi’s fate was sealed by a devastating hepatitis A outbreak traced to green onions served at its Monaca, Pennsylvania location in November 2003. The outbreak infected over 600 people and killed four, making it one of the largest hepatitis A outbreaks in American history. This public health disaster, coming during bankruptcy proceedings, proved insurmountable. Parent company Outback Steakhouse purchased the chain’s assets but closed all U.S. locations, though the brand surprisingly lives on internationally and as a grocery product line of salsas and tortillas—its restaurant business a cautionary tale of how quickly public perception and food safety issues can destroy decades of brand building.

4. Ponderosa and Bonanza Steakhouses

These sister steakhouse chains, named after the fictional ranch in the television show “Bonanza,” once dotted the American landscape with over 600 locations offering affordable steaks and extensive buffets. The concept—combining table service for entrees with self-service buffets—gave middle-class families the steakhouse experience at budget-friendly prices. The chains began struggling in the 1980s as competition increased and consumers developed more sophisticated palates, leading to a series of ownership changes and a merger of the two brands.

The fatal blow came through a combination of an unsustainable business model and the 2008 financial crisis. Parent company Metromedia Steakhouses filed for bankruptcy that year, citing rising food costs that made their budget steak concept unprofitable. While a small number of locations survive today under Homestyle Dining LLC ownership, the chains never recovered their former prominence. Their decline illustrates the challenge of maintaining budget pricing while food costs rise—the very aspect that made them popular became impossible to sustain. The rustic, Western-themed steakhouse with unlimited salad bar gradually became a relic of the past as consumer preferences shifted toward more specialized dining experiences.

5. Burger Chef

Once the nation’s second-largest burger chain behind only McDonald’s, Burger Chef pioneered many fast-food innovations we now take for granted, including the kids’ meal with toy (the “Fun Meal,” which predated McDonald’s Happy Meal), the works bar for customizing burgers, and flame-broiled patties. At its peak in the 1970s, Burger Chef operated 1,200 locations nationwide, featuring memorable mascots like Burger Chef and Jeff. The chain’s decline began when General Foods acquired it in 1968, taking it outside its core business competency.

The beginning of the end came when General Foods sold the struggling chain to Hardee’s parent company in 1982. Hardee’s converted most locations to their brand, effectively ending Burger Chef’s distinct identity. The chain suffered from inconsistent leadership vision and failure to differentiate itself as competition intensified in the fast-food market. Despite being as innovative as McDonald’s in many respects, Burger Chef lacked the marketing muscle and operational discipline of its larger competitor. By 1996, the last Burger Chef location had closed, though its influence lives on in fast-food practices now considered standard. The chain maintains such cultural significance that it was even featured in a plotline of the TV show “Mad Men,” introducing it to a new generation who never tasted its signature Big Chef sandwich.

6. Lum’s

Founded in Miami in 1956, Lum’s expanded to over 400 locations nationwide during the 1960s and 1970s, becoming famous for hot dogs steamed in beer and Ollieburgers (created by celebrity chef James Beard). The casual family restaurant’s signature dish involved a unique cooking method where hot dogs were steamed in beer, creating a distinctive flavor profile that helped the small chain stand out. The chain’s troubles began after being purchased by Wienerwald, a Swiss company, in 1971 for $4 million.

Overexpansion and mismanagement under Wienerwald ownership led to bankruptcy by 1982. The new owners lacked understanding of the American market and took on excessive debt trying to grow too quickly. Despite a fascinating connection to the Kentucky Fried Chicken empire—KFC founder Colonel Sanders sold his company to purchase Lum’s in 1971, though he quickly regretted the decision and sold it to Wienerwald—the chain couldn’t sustain its business model. The last Lum’s restaurant closed in Bellevue, Nebraska in 2017, ending a 60-year run that saw the concept go from a hot dog stand to a nationwide chain and back to obscurity, demonstrating how quickly restaurant fortunes can change under different management philosophies.

7. Kenny Rogers Roasters

Founded in 1991 by country music star Kenny Rogers and former Kentucky governor John Y. Brown (who had previously built Kentucky Fried Chicken), this chain specialized in wood-fired rotisserie chicken positioned as a healthier alternative to fried chicken. The concept expanded rapidly to over 350 locations worldwide during the 1990s, gaining additional fame when featured in a 1996 “Seinfeld” episode where Kramer becomes obsessed with their chicken. Initial success came from savvy celebrity marketing and riding the wave of health consciousness that made rotisserie chicken popular in the 1990s.

The chain’s U.S. presence collapsed almost as quickly as it grew, filing for bankruptcy in 1998 after overexpanding in a market that became saturated with rotisserie chicken options from supermarkets and competing restaurants. Nathan’s Famous hot dogs purchased the company in 1999, before selling to their current owner, Asian-based Roasters Asia Pacific. In an ironic twist, while Kenny Rogers Roasters has virtually disappeared from its country of origin, it thrives today in Asia, particularly Malaysia and the Philippines, where it operates as a higher-end dining option. Its failure in the American market demonstrates how even celebrity branding can’t overcome operational challenges and changing consumer preferences in the hypercompetitive restaurant industry.

8. Bennigan’s

Once a pioneer in the casual dining segment, Bennigan’s combined an Irish pub theme with an extensive menu of American fare, creating the blueprint for what would later be called “eatertainment.” Founded in 1976 by Norman Brinker (the same restaurant visionary behind Steak and Ale), the chain expanded to over 300 locations known for potato skins, Monte Cristo sandwiches, and a festive bar atmosphere that made it a popular happy hour destination. The chain’s decline began after multiple ownership changes removed it from Brinker’s original vision.

The fatal blow came in July 2008 when parent company Metromedia Restaurant Group suddenly filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, closing all 150 corporate locations overnight without warning. Employees and customers arrived to find doors locked and signs announcing the closure. Franchise locations survived, but the brand never recovered from this abrupt collapse. The spectacular failure resulted from a perfect storm of problems: unsustainable debt, rising food costs during the 2008 economic crisis, and failure to update the concept as competitors evolved. Though a new ownership group maintains a small number of locations today, Bennigan’s serves as a case study in how quickly a national chain can disappear when financial mismanagement meets changing market conditions.

9. Gino’s Hamburgers

Co-founded by Baltimore Colts football star Gino Marchetti in 1957, this East Coast chain combined sports celebrity appeal with quality burgers, becoming one of the first to successfully leverage athlete endorsement in the restaurant industry. At its peak, Gino’s operated over 350 locations across the Mid-Atlantic states, known for the “Gino Giant” burger (which inspired McDonald’s Big Mac) and later for introducing Kentucky Fried Chicken to the region through a co-branding arrangement. The chain developed intense regional loyalty, particularly in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Delaware.

Gino’s demise came after being acquired by Marriott Corporation in 1982, which promptly converted most locations to their Roy Rogers brand. The acquisition essentially erased a beloved regional chain overnight, despite its profitability and customer loyalty. A brief revival attempt called Gino’s Burgers and Chicken launched in 2010 but failed to recapture the magic, closing its last location in 2014. The story of Gino’s illustrates how regional chains with strong identities often lose their appeal when absorbed by larger corporations that fail to understand their cultural significance. For many Baby Boomers in the Mid-Atlantic states, Gino’s represents not just a restaurant but a lost piece of their community identity.

10. Wetson’s

Often called “New York’s answer to White Castle,” Wetson’s was a regional fast-food chain that operated approximately 70 locations in the New York metropolitan area from 1959 to 1975. The chain was famous for its 15-cent hamburgers, distinctive yellow and white tiled buildings, and the slogan “Look for the Yellow Roof.” Wetson’s gained a loyal following for offering quick, affordable meals in America’s largest urban market before the major national chains had fully established themselves in the region. At its peak, Wetson’s represented successful local entrepreneurship competing against emerging national brands.

The chain’s collapse came as national fast-food giants McDonald’s and Burger King aggressively expanded into the New York market in the early 1970s, bringing standardized operations and massive advertising budgets that the regional chain couldn’t match. Wetson’s was ultimately acquired by Nathan’s Famous in 1975, with most locations converted or closed. The story of Wetson’s reflects a pattern repeated across America as regional fast-food chains were overwhelmed by national competitors during the industry’s consolidation phase. Though Wetson’s has been gone for over 45 years, it remains a nostalgic touchpoint for New Yorkers of a certain age who remember when fast food still had strong local character before national homogenization.

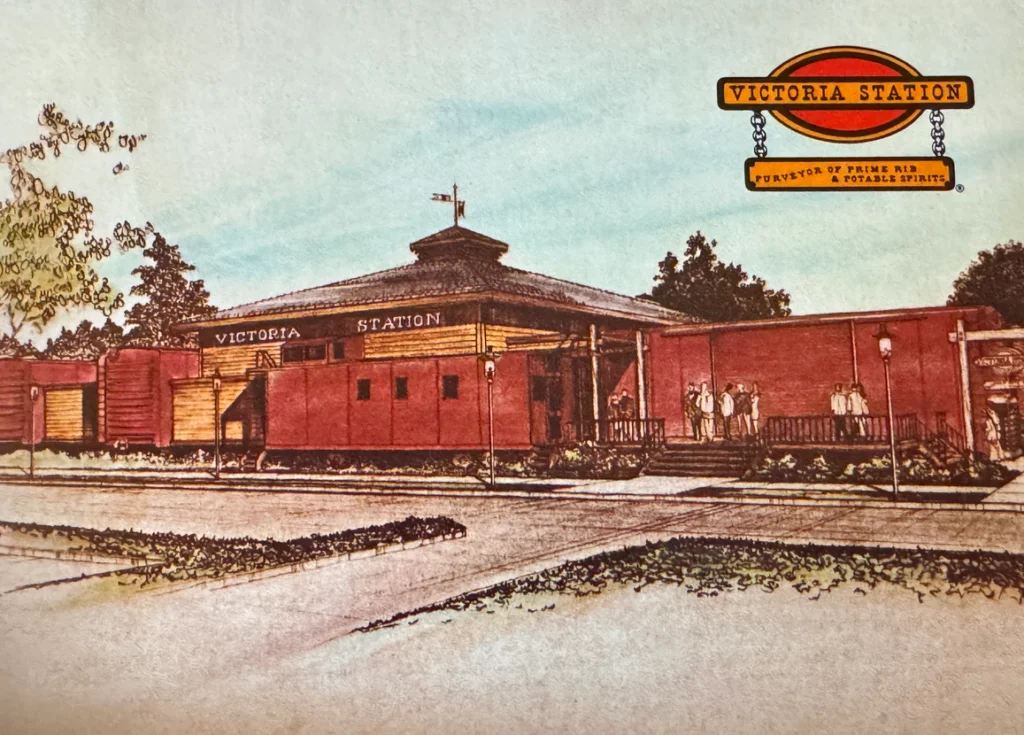

11. Victoria Station

This unique concept restaurant chain built locations from actual retired railroad cars, creating a distinctive British railway station theme that stood out in the 1970s dining landscape. At its peak, Victoria Station operated 100 locations known for prime rib, a salad bar, and cocktails served in an atmosphere filled with authentic railroad memorabilia. The chain rode the theme restaurant wave before it was common, offering not just meals but transportive experiences that made dining an event. The concept was particularly popular for special occasions, combining novelty with quality food.

Victoria Station’s decline began with misguided expansion in the late 1970s into locations that couldn’t support the high overhead of their elaborate themed buildings. The final derailment came through a disastrous 1980s management decision to pivot toward cheaper menu items and casual positioning, confusing their customer base who came specifically for the premium experience. Filing for bankruptcy in 1986, the chain serves as a cautionary tale about abandoning core brand identity in pursuit of broader appeal. The failure of Victoria Station demonstrates how concept restaurants face unique challenges—when the novelty fades, they must deliver either exceptional food or continually refreshed experiences to survive. Today, only a single location reportedly remains in Salem, Massachusetts, the last stop of what was once an innovative dining destination.

12. Minnie Pearl’s Chicken

One of the most infamous restaurant failures in American history, Minnie Pearl’s Chicken attempted to capitalize on the success of Kentucky Fried Chicken by licensing the name and image of Grand Ole Opry star Minnie Pearl (Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon). Launched in the late 1960s, the chain expanded rapidly to over 500 locations and became a publicly traded company with a stock price that soared despite most restaurants not yet being operational. The country comedy star had no fast-food experience but lent her name and wholesome image to the venture, appearing in advertisements wearing her signature hat with the price tag still attached.

The chain’s spectacular collapse came from a combination of poor quality control, mismanagement, and what amounted to a stock market bubble. Most crucially, while they sold franchises at a frantic pace, they failed to develop standardized recipes or operating procedures, meaning the food varied wildly between locations. The Securities and Exchange Commission eventually investigated the company for financial irregularities, and the chain folded by 1971. The cautionary tale of Minnie Pearl’s Chicken has become a business school case study in the dangers of expanding too quickly without operational fundamentals in place. The failure was so complete that many locations never actually opened, despite being counted in official company figures.

13. Red Barn

With its distinctive barn-shaped buildings and memorably rural branding, Red Barn grew to over 400 locations across 19 states and parts of Canada from its founding in 1961 through the late 1970s. The chain was known for signature items like the “Big Barney” and “Barnbuster” burgers and an early salad bar called the “Fixins Bar.” Red Barn’s family-friendly atmosphere and architectural distinctiveness made it a beloved regional competitor to the major fast-food chains, particularly throughout the Midwest and parts of the East Coast.

Red Barn’s downfall resulted from a complex series of corporate acquisitions that left the chain without focused leadership. The fatal mistake came when parent company Motel 6 sold the chain to City Investing Company in the late 1970s but retained ownership of the actual Red Barn trademark. The new owners were forced to rebrand locations as “The Farm” and other names, losing brand recognition. Without a cohesive identity, the chain gradually disbanded through the 1980s, with franchisees converting to other brands or becoming independents. The Red Barn story demonstrates how intellectual property issues can unexpectedly doom even successful restaurant concepts. Today, devoted fans maintain websites and Facebook groups celebrating the chain, sharing memorabilia and memories of a restaurant whose distinct identity was legally erased.

These restaurant chains, once fixtures of American dining culture, serve as reminders of how quickly fortunes can change in the volatile food service industry. Economic pressures, changing consumer tastes, management missteps, and sometimes simple bad luck transformed these thriving businesses into footnotes of culinary history. While their signs may have been taken down and their buildings repurposed, these chains live on in the memories of diners who can still taste their signature dishes and recall the distinctive experiences they provided—memories perhaps more flavorful through the seasoning of nostalgia than they ever were in reality.