Before GPS navigation and smartphone entertainment, the great American road trip relied on roadside curiosities to break up the monotony of endless highways. The 1970s represented the golden age of these attractions—a perfect storm of kitschy Americana, post-hippie creativity, and pre-internet boredom that produced monuments to weirdness along highways nationwide. Armed with paper maps and a willingness to follow hand-painted signs down mysterious exits, travelers discovered these monuments to American eccentricity that somehow burned themselves into our collective memory. Here are twelve of the most delightfully bizarre attractions that made ’70s road trips unforgettable experiences.

1. Foamhenge, Natural Bridge, Virginia

Long before foam was recognized as an environmental hazard, it was celebrated as an artistic medium at Foamhenge—a full-scale replica of Stonehenge constructed entirely from styrofoam blocks. Created by artist Mark Cline in 2004 as an April Fool’s joke (though it has roots in similar ’70s attractions), this monument to American ingenuity and questionable material choices became an unexpected tourist destination despite its complete lack of historical significance or cultural authenticity. The stark white formation, initially spray-painted gray to resemble stone, gradually weathered to create an even more surreal appearance as the decades passed. Atlas Obscura fills in the map on some of the mystique surrounding this peculiar attraction.

What made Foamhenge remarkable wasn’t just its size (identical to the real Stonehenge) but the absolute commitment to presenting this foam monument with the same reverence as its ancient counterpart. Informational placards discussed the astronomical alignments and potential purposes with complete seriousness, never acknowledging the inherent absurdity of contemplating ancient mysteries while standing next to giant blocks of industrial petrochemical products. For ’70s families on tight budgets, Foamhenge provided international cultural exposure without the expense of traveling to England—though the nearby Natural Bridge KOA campground hardly replicated the Salisbury Plain experience.

2. Bonnie and Clyde’s Death Car, Various Locations

The ’70s fascination with outlaw culture found perfect expression in the touring exhibition of the bullet-riddled Ford V8 allegedly driven by Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow during their final moments. This macabre attraction appeared at county fairs, shopping centers, and tourist traps throughout the decade, drawing crowds willing to pay to see authentic bullet holes from the famous 1934 ambush. What visitors didn’t know (and tour operators didn’t mention) was that dozens of “authentic” death cars circulated simultaneously, with bullet holes often added by enterprising showmen rather than law enforcement officers. All That’s Interesting dives into the grim history behind this notorious part of the end of their lives.

The car’s popularity wasn’t just about true crime fascination but reflected the era’s romanticization of Depression-era bandits, fueled by the stylish (and heavily fictionalized) 1967 film starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. Parents who had grown up during the actual crimes often provided impromptu history lessons to children, though these explanations sometimes conflated movie scenes with historical events. The death car’s appeal transcended its questionable authenticity—it represented accessible history, allowing ordinary Americans to stand inches from what they believed was a genuine artifact from a notorious crime scene, creating an emotional connection to historical events that textbooks couldn’t provide.

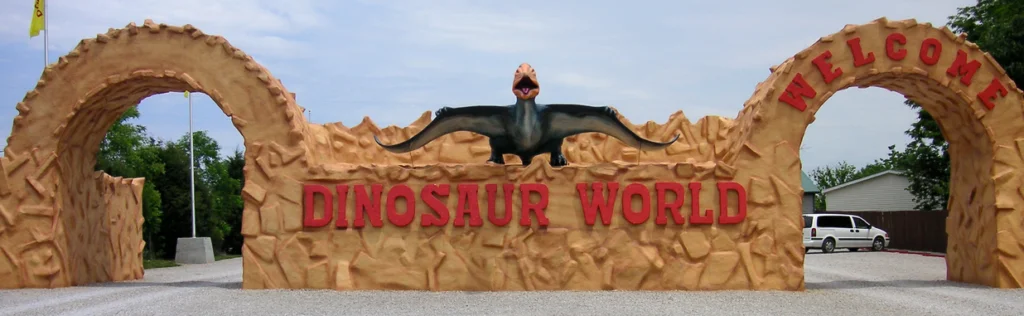

3. Dinosaur World, Cave City, Kentucky (and various locations)

Nothing captured the ’70s roadside aesthetic quite like anatomically questionable dinosaur replicas looming over the highway, promising prehistoric adventures that invariably involved gift shops. Dinosaur World featured over 150 life-sized dinosaur statues arranged along nature trails, looking simultaneously terrifying and comical with their faded paint jobs and occasionally missing appendages. The dinosaurs reflected the scientific understanding of the era—meaning they were wildly inaccurate by modern standards—but their imposing presence created genuine wonder for children raised on Land of the Lost reruns. Alluring World puts into perspective the huge scope of this attraction, where hopefully they decided to spare no expense and skipped breeding raptors.

The prehistoric beasts were constructed from concrete and fiberglass by local artisans who prioritized dramatic effect over scientific accuracy, resulting in creatures that paleontologists wouldn’t recognize but children absolutely adored. What made Dinosaur World special wasn’t just the statues but the immersive commitment to the prehistoric theme, from “fossil digs” (sifting through sand for shark teeth) to the “authentic” cave paintings that somehow featured dinosaurs and humans together. For many ’70s children, these roadside dinosaurs created more lasting memories than museum exhibits, precisely because they were allowed to climb on them, pose for photos in gaping mouths, and purchase plastic replicas that would eventually be left at subsequent motel stops.

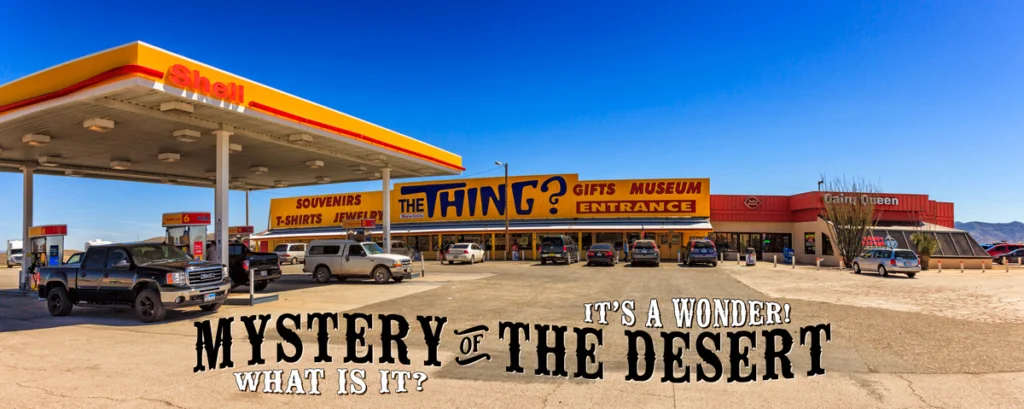

4. The Thing, Dragoon, Arizona

Few attractions embodied the ’70s roadside mystery aesthetic quite like The Thing, advertised by over 200 simple black and yellow billboards asking “WHAT IS IT???” stretched across three states. The buildup was masterful—signs began appearing hundreds of miles before the actual attraction, creating an irresistible curiosity that compelled even reluctant parents to exit the highway. For your admission fee (originally 50 cents), visitors followed yellow footprints through three metal sheds containing an increasingly strange collection of oddities—alleged torture devices, bizarre artwork, and historic cars—all building toward the reveal of “The Thing” itself.

The final payoff (no spoilers here, though the internet has ruined the surprise) wasn’t nearly as impressive as the journey, but that wasn’t really the point. What made The Thing unforgettable was the perfect exploitation of road trip psychology—the billboards created an itch that could only be scratched by stopping, and the bizarre collection of unrelated artifacts in the exhibit halls perfectly captured the ’70s fascination with the strange and unexplained. The attraction perfectly balanced mild disappointment with genuine weirdness, creating a shared cultural experience that prompted “We drove all that way for THAT?” reactions that somehow still left travelers feeling they’d gotten their money’s worth in pure, unfiltered oddity.

5. The Mystery Spot, Santa Cruz, California

In a decade obsessed with paranormal phenomena, the Mystery Spot capitalized perfectly on America’s fascination with unexplained forces. Visitors walked through a tilted cabin where water seemingly flowed uphill, people appeared to grow or shrink based on where they stood, and the laws of gravity seemed optional rather than mandatory. Tour guides offered pseudo-scientific explanations involving alien spacecraft, magnetic anomalies, and interdimensional vortexes—all delivered with complete seriousness while wearing safari outfits that added extra authenticity to the bizarre proceedings.

The attraction’s iconic black and yellow bumper stickers became coveted road trip trophies, turning family station wagons into traveling billboards for this gravitational anomaly. What made the Mystery Spot truly special wasn’t just the optical illusions (which were clever but simple), but the complete commitment to its mythology—transforming what was essentially a tilted shack in the woods into a destination worth driving hours to experience. Families would debate the “real” explanation for days afterward, with children insisting on the alien theory while parents attempted increasingly complicated physics explanations that eventually dissolved into “well, something weird is definitely happening there.”

6. Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo, Texas

In 1974, an art collective called Ant Farm buried ten Cadillacs nose-down in the Texas dirt, their tail fins pointing skyward at the exact angle of the Great Pyramid of Giza. This installation—simultaneously a tribute to America’s automotive evolution, a protest against consumerism, and a very strange thing to encounter while driving through Texas—quickly became an interactive experience as visitors began adding their own touches with spray paint. By the late ’70s, the once-colorful Cadillacs had become mobile canvases, with layers of graffiti continuously transforming the installation into something new yet eternally the same.

What made Cadillac Ranch unforgettable wasn’t just its visual impact but its perfect embodiment of ’70s counterculture seeping into mainstream America. Located along Route 66, it represented a perfect marriage between traditional road trip culture and the artistic experimentation of the era. Unlike most attractions that prohibited touching, Cadillac Ranch evolved specifically because visitors interacted with it, making each family’s experience unique while contributing to the collective artwork. Parents who had visited in their youth returned with children decades later, finding comfort in the fact that while the graffiti had changed completely, the essential bizarre vision—luxury cars buried in dirt—remained gloriously, stubbornly the same.

7. Wall Drug, Wall, South Dakota

What began as a desperate Depression-era marketing gimmick—offering free ice water to parched travelers—evolved by the 1970s into a 76,000-square-foot labyrinth of Western kitsch that attracted over two million visitors annually. Wall Drug’s famous billboard campaign stretched for hundreds of miles in every direction, creating an anticipation that the actual store—despite its impressive size and collection of oddities—could never quite satisfy. The establishment featured an eclectic mix of genuine pharmacy, tacky souvenir shops, animatronic displays, and an 80-foot concrete dinosaur that somehow fit the Western theme through sheer force of commitment.

The attraction’s genius lay in its absolute refusal to make sense—visitors wandered from rooms with valuable Western art collections to areas featuring mechanized gorillas playing musical instruments, all while being reminded that free ice water awaited at the end of this consumer fever dream. For children of the ’70s, Wall Drug represented a perfect storm of road trip weirdness—the endless billboard buildup, the incomprehensible layout that made parents lose track of children, and the jackrabbit photo-op stations that produced uncomfortable family photographs still lurking in albums nationwide. Despite its commercial nature, Wall Drug somehow transcended mere shopping to become a genuine cultural phenomenon—the roadside attraction equivalent of a variety show that refused to specialize.

8. South of the Border, Dillon, South Carolina

Pedro, the cartoon mascot with a sombrero and questionable accent, beckoned travelers with hundreds of billboards that began appearing almost 200 miles before this Mexican-themed wonderland materialized on the North Carolina-South Carolina border. The attraction’s neon-lit 200-foot sombrero tower could be spotted from miles away, promising exotic experiences that, in reality, consisted mainly of fireworks shops, tacky souvenirs, and bathrooms labeled “Señors” and “Señoritas.” The magnificent cultural insensitivity was matched only by the spectacular commitment to the bit—everything from the “Pedroland” amusement area to the “Pedro’s Weather Report” (a giant thermometer) embraced the theme with unbridled enthusiasm.

What made South of the Border truly unforgettable wasn’t just its size (over 100 acres!) but the absolute sensory overload it provided—neon colors, giant fiberglass animals, and endless opportunities for Polaroid moments. For children of the ’70s, the attraction represented a delightful form of culture shock, introducing many to their first (highly inauthentic) “Mexican” food and creating the mistaken impression that sombreros were traditionally neon pink. Despite occasional renovations, South of the Border remains essentially unchanged—a preserved-in-amber monument to a time when cultural sensitivity took a backseat to giant concrete statues and gift shops selling shot glasses.

9. Prairie Dog Town, Oakley, Kansas

“See the World’s Largest Prairie Dog!” proclaimed hand-painted signs stretching across western Kansas, beckoning travelers toward a roadside zoo featuring a concrete rodent statue that was, indeed, significantly larger than actual prairie dogs. The attraction’s bizarre menagerie included five-legged cows, two-headed calves, and living prairie dogs trained to perform the impressive feat of eating peanuts from visitors’ hands. The gift shop sold mummified toads dressed as cowboys—a souvenir category that thankfully remains extinct—while the snack bar offered treats that seemed designed specifically to test the durability of 1970s family station wagons’ upholstery.

What made Prairie Dog Town memorably weird wasn’t just the concrete prairie dog (impressive though it was) but the absolute commitment to showcasing biological oddities both living and preserved. The attraction embodied the ’70s roadside philosophy that education and exploitation were essentially interchangeable concepts, teaching children about wildlife while simultaneously presenting genetic mutations as entertainment. For many families, these roadside animal attractions provided children’s first close encounters with live animals beyond household pets, creating memories that were equal parts educational and traumatizing as the scent of dozens of prairie dog burrows accompanied them back to the family car.

10. Wigwam Village Motels, Various Locations

Nothing captured the cultural insensitivity and architectural creativity of mid-century roadside America quite like the Wigwam Village chain, where families could fulfill their questionable dream of sleeping in concrete tepees (consistently mislabeled as “wigwams”). By the 1970s, these distinctive motor courts had become road trip destinations in themselves, promising an “authentic” Native American experience that was, in reality, about as authentic as the nearby “trading posts” selling rubber tomahawks and headdresses manufactured in Taiwan. Each unit featured modern amenities like air conditioning and television awkwardly retrofitted into the conical concrete structures.

What made these villages unforgettable wasn’t just their distinctive silhouette against the sunset but the absolute commitment to the theme, from the central office building (a larger tepee) to the arrangement in a semi-circle “just like real Indians.” Children found the experience magical, while parents appreciated the novelty that distracted from the questionable mattress quality and acoustics that turned snoring into a communal experience. Despite their problematic concept, the remaining Wigwam Villages have achieved historic preservation status as quintessential examples of American roadside architecture—monuments to an era when “cultural appreciation” meant building geometrically challenging hotel rooms based on loose interpretations of indigenous housing.

11. Alligator Farms, Throughout the South

The 1970s represented peak alligator tourism, with dozens of roadside attractions throughout the southern states offering visitors the opportunity to see these prehistoric creatures up close—often while eating ice cream. These establishments ranged from legitimate conservation efforts to glorified concrete pools where lethargic reptiles awaited their daily chicken feeding spectacle. The typical alligator farm featured grandstands around a central pit, an aggressive sign policy warning against external food sources (for visitors or alligators), and gift shops offering baby alligator heads preserved in various poses—from wearing sunglasses to holding miniature beer cans.

What made these attractions unforgettable wasn’t just the alligators but the complete ecosystem of weirdness that surrounded them—from the “gator wrestlers” (usually sunburned men in questionable safari outfits) to the inexplicable addition of unrelated attractions like “mystery houses” or collections of two-headed animals in formaldehyde. These farms reflected the ’70s approach to wildlife tourism, where educational components provided thin justification for what was essentially a reptilian circus. For many northern children, these attractions provided first encounters with creatures previously only seen in National Geographic, creating core memories of humidity, strange smells, and the distinctive sound of dozens of alligator jaws simultaneously snapping shut during feeding demonstrations.

12. Rock City, Lookout Mountain, Georgia/Tennessee

“See Seven States!” promised the famous barn roofs and birdhouses advertising this geological oddity straddling the Georgia-Tennessee border. Rock City combined natural rock formations with aggressively whimsical enhancements—narrow passages dramatically named “Fat Man’s Squeeze,” garden gnomes incongruously placed among ancient boulders, and a bizarre indoor black-light diorama called “Fairyland Caverns” featuring disturbing fluorescent depictions of classic fairy tales. The signature moment came at Lover’s Leap, where a coin-operated binocular viewfinder and helpful painted diagram helped visitors convince themselves they could indeed see seven states simultaneously.

What made Rock City transcend typical tourist trap status was its perfect blend of natural beauty and manufactured weirdness—the genuine impressiveness of the massive rock formations paired with the utterly inexplicable addition of garden gnomes and glow-in-the-dark elves. The attraction embodied the maxim that nothing in nature can’t be improved with gift shops and snack bars, creating an experience that somehow remained in memory as both legitimately impressive and spectacularly tacky. The marketing campaign itself became legendary—at its peak, over 900 barns across the eastern United States were painted with the simple message “See Rock City,” creating a nationwide scavenger hunt that turned the advertisement itself into a form of roadside attraction.

These bizarre roadside worlds represented more than just quirky stops on family vacations—they were physical manifestations of American creativity, entrepreneurial spirit, and commitment to the deeply weird. Unlike today’s carefully focus-grouped attractions designed for Instagram moments, these ’70s oddities sprang from individual visions, often built by hand and promoted through hand-painted signs and word-of-mouth. Their unashamed embrace of the unusual created indelible memories for a generation of children pressed against station wagon windows, spotting dinosaur statues on the horizon or counting the miles between “South of the Border” billboards. In their concrete giants, mysterious vortexes, and questionable historical reenactments, they captured something essential about the American character—the desire to create monuments to imagination in the most unexpected places, transforming ordinary road trips into expeditions through landscapes of pure wonder.